One of the greatest challenges of writing better stories is knowing exactly which scenes to write. The best scenes focus on the core elements of conflict — which means before you can write amazing scenes, you have to find the central conflict in a story.

You may have a great story idea in your head. But the specifics of it — which moments to capture — are unclear. The result is often writer’s block, or a story that feels “off,” meaning it isn’t focused on the right stuff.

That’s where Conflict Mapping can make your writing even better!

Strong scenes come from strong plans. And visualizing the types of conflict between your characters is a great way to do just that.

When Conflict in a Story Is Unclear

Conflict is essential to a strong story.

To give zest to your plot and move it forward, you need to integrate a type of conflict in every scene.

This can be seen as a moral conflict that sparks an internal struggle, or a force of external conflicts that threaten a character in a physical or other way.

Rarely does a story’s conflict magically appear in our minds. That’s because inspiration frequently comes from other sources: beauty, music, or situations. Rarely are we inspired by a focused sequence of events built around pursuing a goal (which is what a story is), because this tends to happen too quickly to note.

So when we sit down to write, we’re really just translating the image or idea we had into a word-picture.

Except those aren't major conflicts.

I experienced this in 2012 when I decided to write a murder mystery about a family in New Orleans. My wife and I even went on vacation there, staying just outside the French Quarter.

And while we saw a lot of beautiful things, heard some amazing music, and came up with many interesting situations, strong story conflict did not come to us as we sweated our way through the city.

How can we translate inspiration and ideas into clear conflict in a story?

Simple: Start by drawing two circles.

Conflict Map: Drawing a Relationship

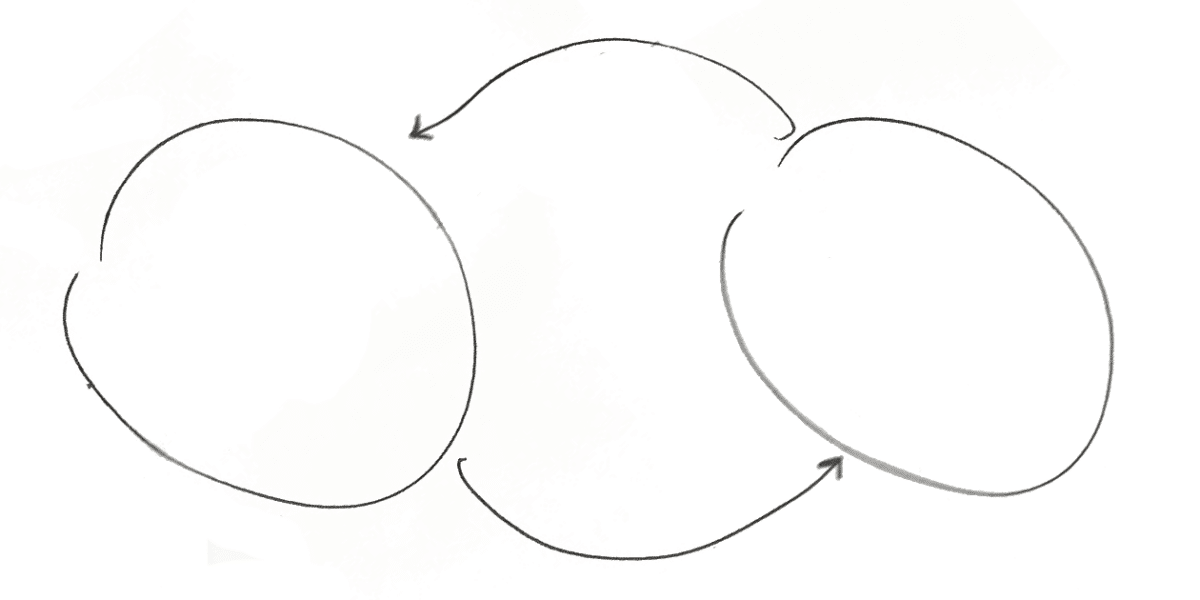

To begin your Conflict Map, draw two empty circles. Then, connect them with arcing arrows, like this:

Now, decide which two people are in a relationship in your story. You don’t need names. Just people. Mom and daughter? Boyfriend and girlfriend? Owner and dog? You decide. Just put something in there.

The point is that you are intentionally developing multiple characters in a a story, which gives you an opportunity to create conflict between people, particularly between one character and your protagonist.

Once you've done this, on the arrow extending from a character’s bubble, write what they want from the other character. It can be physical (preferable) or non-physical (okay — but add something physical to go with it, like “affection = hug”).

Then, consider what the other character might want from the first. Write it on their arrow.

As you do this, consider traits that might be essential to each character. Jot them in the circles. This is the time to create without any fear or reservations.

And to keep it fear-free, do it in pencil so you can erase and alter to your heart’s delight!

Create 4 Relationships

According to Robert McKee, there are four character types that nearly every protagonist has a relationship with in most stories. Whenever I’m building a new story in a new world, I find this to be a fantastic starting place, and it’s what I did as I built the world of my New Orleans play.

The four character types to fill first, as you plan, are:

- Friend: What one might want from a friend? What does the exchange of goals look like in friendship?

- Authority: How does this relationship create benevolent and/or negative energy?

- Love: How does the protagonist think of, and possibly plan to, pursue their love interest?

- Enemy: Who opposes the protagonist? Is it direct opposition (contradicting the protagonist’s goal), or competitive (pursing the same or a similar goal)?

Once you’ve established what the protagonist wants from each of these characters, draw arrows connecting the characters to each other. What might the Authority want from the Friend? The Friend from the Love? And so on.

Not only does this give you more characters to work with, but it plants the seeds for plenty of conflict that will blossom into strong scenes. When characters are engaged in authentic relationships, the conflict between them occurs more naturally. It doesn't feel unclear, nor does it come out of nowhere.

So plan out two (or more) characters who want things from one another that cannot easily be given.

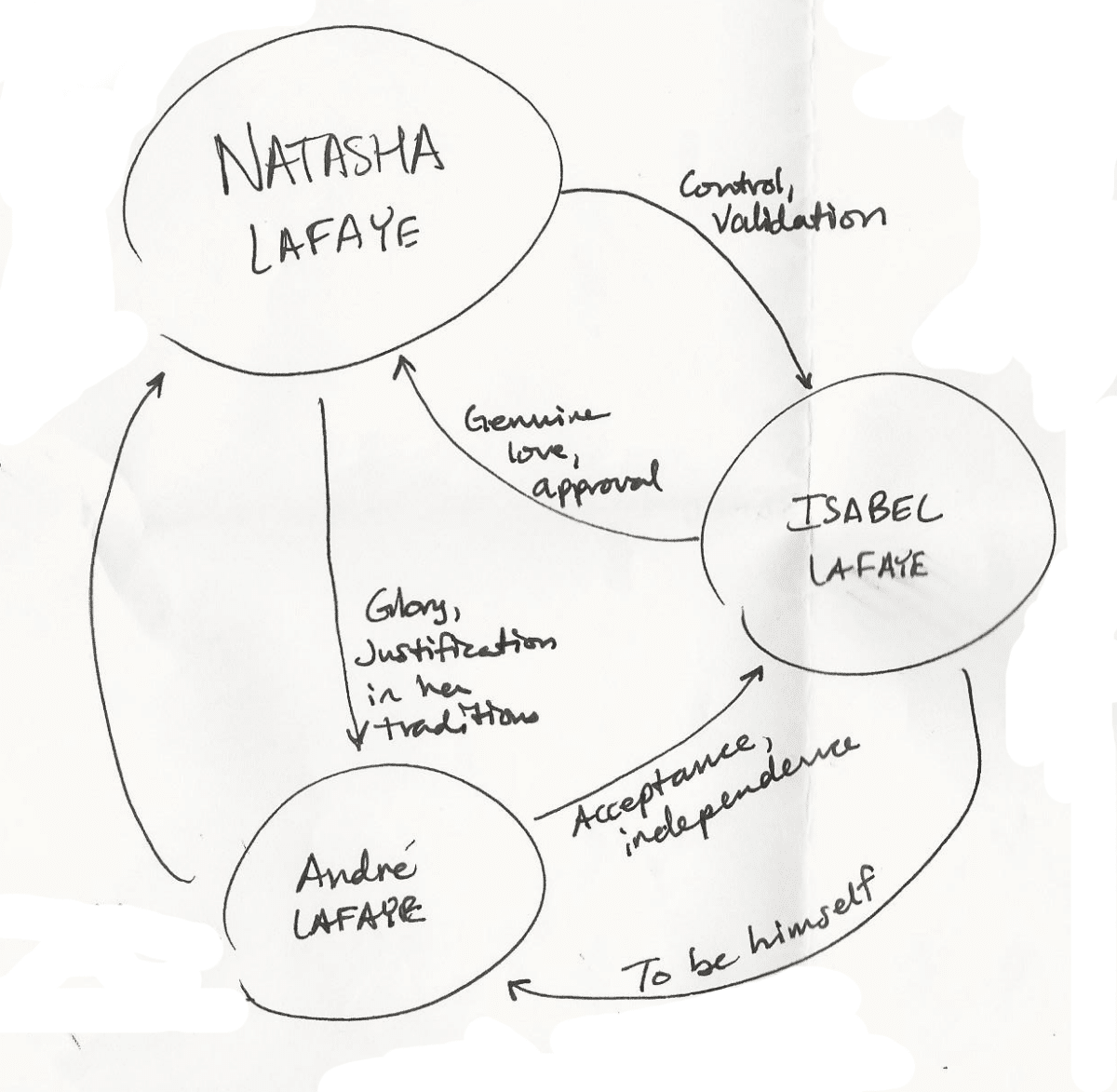

You can see my protagonist, Isabel’s, relationship with two of these characters below: the Friend (her adopted brother) and her Authority (her mother, Natasha). Note that I hadn't figured out Andre's goal, yet. This truly is a way to discover your protagonist's “world!”

Add Goals and Go

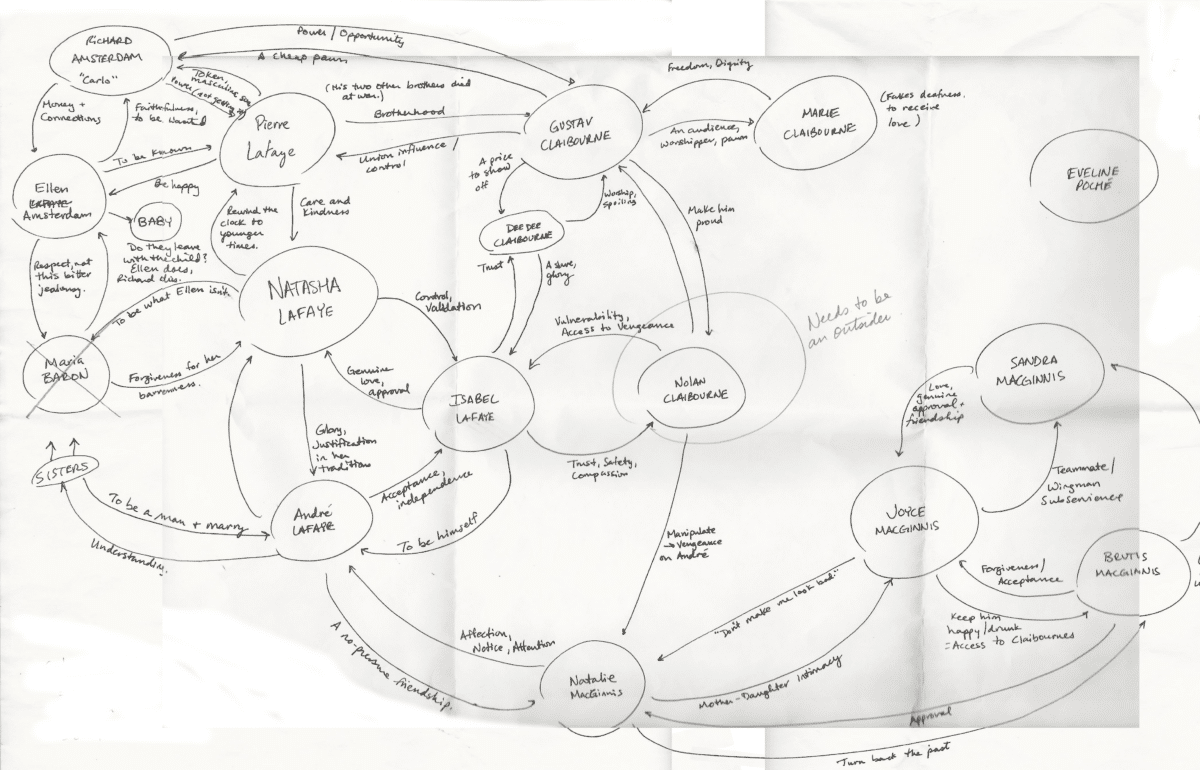

When I was done with my Conflict Map, it was so big that my play couldn’t possibly contain all the characters and relationships. So I cut five of them!

Yet the map was invaluable for planning the relationships and conflict I would need to make the story work. It gave me the seeds of great, dramatic scenes.

And the result was a fun, thrilling play that surprised everyone with its authentic conflict.

There is one thing I didn’t do, though, that I highly recommend you do: Add action verbs to each character’s goal. There’s a big difference between an Enemy who chooses to “annihilate” to get their goal, versus one who “humiliates.”

My protagonist, a bride-to-be, chose to “soothe” her overbearing mother in order to get her goal of “genuine love and approval. The play would have been much different if she chose to blame, lie, or ignore. Verbs matter, and they can help you as you craft these crucial scenes.

You can check out a large view of my final map here. It’s a mess—four pieces of paper taped together and scanned into the computer in three batches.

Every Story Needs Conflict

Conflict is crucial in a plot and between characters and other forces, like the environment, that challenge the protagonist.

To help you come up with conflict, turn to your planning process. Remember, this is supposed to be messy, not a perfect, finished product. A well-executed plan can lead to a wonderful final product.

Whether or not the main conflict in your scene is internal conflict or minor characters blocking your protagonist and their pursuit of their scene goals, or other external obstacles standing in their way, engaging conflicts will advance a plot and keep your readers engaged.

To plan and implement conflict into your story, give Character Mapping a try. And watch as your story get stronger right away!

How do you find the conflict in a story? Let us know in the comments.

PRACTICE

Take fifteen minutes to draft a character map for your protagonist’s four “world” characters: Friend, Authority, Love, and Enemy. Make sure arrows go out from each character to the others, identifying what each wants in each relationship. Then, add action verbs that describe how each character will go about getting what he/she wants.

In the practice box below, summarize one of these relationships by sharing what each character wants from the other, and what they plan to do to get it.

When you're done, be sure to leave feedback for your fellow writers in the comments!

You deserve a great book. That's why David Safford writes adventure stories that you won't be able to put down. Read his latest story at his website. David is a Language Arts teacher, novelist, blogger, hiker, Legend of Zelda fanatic, puzzle-doer, husband, and father of two awesome children.

Hallo David, thank you so much for that great lecture. Unfortunately, for me, the images of your conflict maps are not loading. Is there a way they could be sent to me? It looks like the answer to many questions I had. Thank you very much!

Hi Karin! Thanks for your comment, as I saw the same thing. I think there was a glitch with the photos over the weekend, but it appears to be fixed now. Try refreshing and see if they show for you now too.