The falling action is a literary term you hear thrown around in middle school writing classes and on creative writing blogs, but what is it? And will it actually help you understand, and maybe write, a good story?

In this post, I’m going to define falling action, talking briefly about its origin as a literary term and its place in dramatic structure, and then talk about whether you should incorporate it into your story structuring process.

Spoiler alert: you shouldn't.

Definition of Falling Action

In dramatic structure, it is one of the six elements of plot structure, occurring just before the resolution.

It is quite short, often just one scene, and in many stories it does not even exist.

Before we get into whether you, dear writer, should use falling action in your story, let’s talk about what the falling action is. But first we need to review dramatic structure to see how falling action fits into dramatic structure.

Where Falling Action Fits in Dramatic Structure (or Doesn't)

Dramatic structure is an idea, originating in Aristotle’s Poetics, that effective stories can be broken down into elements. At The Write Practice, we define six elements of dramatic structure:

Many story structure frameworks, notably Freytag's Pyramid, place the falling action between the climax and denouement, like this:

- Inciting Incident

- Rising action

- Climax

- Falling Action

- Denouement

How did the falling action arrive there? And why do we not include it in our story structure framework?

To answer that, you have to understand a bit of the history of story structure, especially the history of the climax in a plot.

A Brief History of the Falling Action

The term “falling action” was first popularized by a German novelist named Gustav Freytag. Freytag’s Pyramid has become the most commonly taught plot structure framework, finding its way into middle and high school classrooms as well as into the educations of thousands of writers.

However, if you look closer at Freytag's plot framework, you start to realize that he understood story structure radically different from how it’s taught today.

Freytag was really interested in just one type of story: the tragedy. He thought it was premier form of storytelling. All the novels he wrote were tragedies, and nearly all of the stories he studied in Freytag's Technique are tragedies.

His plot diagram was influenced by this preference and follows a tragic story arc (specifically, the Icarus story arc).

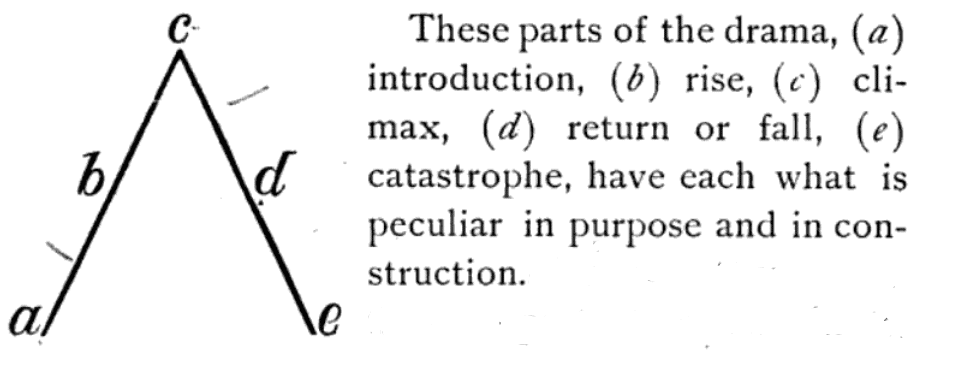

Freytag believed every story contains two halves, a play and a counterplay, with the climax in the middle.

This is the plot diagram from the 1863 version of Freytag's Technique of the Drama, the first plot diagram in the world.

But it's also a bit strange, since the climax, according to Freytag, appears in the exact middle of the story.

To use Romeo and Juliet as an example, the climax—according to Freytag—occurs right after Romeo kills Tybalt in retaliation for Tybalt killing Mercutio. Note that killing Tybalt is not the climax. Instead, it's when Romeo and Juliet part ways.

Huh?

If you're confused, that makes sense, because it's really confusing. Freytag is essentially saying that one of the moments of lowest action in the whole story is actually the climax. It doesn't make sense.

Most people analyzing that story today, even the ones who say they're following Freytag’s Pyramid, would say that the climax occurs when Romeo commits suicide, mistakenly thinking Juliet is dead, and Juliet, waking up to him dying, commits suicide in response.

But that's because Freytag meant a different thing by climax than we do now. For Freytag, the climax is the turning point in a story, the reversal, when things that were going well for the main character start to go badly.

In other words, the climax is a completely different thing.

Freytag’s Climax: turning point in the middle of a story

Modern Climax: highest moment of action in a story where the central conflict comes to a head, usually the second or third to last scene

This miscommunication between Freytag and modern writer and teachers of story structure causes so many problems, and the biggest problem is a misunderstanding of what the falling action is.

Freytag vs. Modern Story Structure

In Freytag's framework, the falling action makes complete sense. After all, if the turning point/climax is in the middle of the story, then nearly half of the plot would be the falling action!

But if you're using a more modern understanding of climax, then the falling action occurs close to the end of the story.

Which means that in well constructed stories, the “falling action” might only be one scene. It might not exist at all!

For example, in Romeo and Juliet, the climax (the main character's dual suicide) occurs in the second to last scene. If the denouement is the last scene, then the falling action doesn't exist.

This also means if you use this model, as most of us do, the falling action is a really unhelpful term, since it may be just one or two scenes or may not exist at all.

Freytag himself makes the case that the falling action isn't an important term, since in his own book on dramatic structure, Freytag’s Technique of the Drama, he doesn't even include a section on the falling action. He explores every other plot element in detail, from the rising action (rising movement, in his framework) to the climax to the denouement (catastrophe, in his framework). But he neglects to include a section on the falling action.

Some Stories DO Have Falling Action

While they're not universal in all stories, some stories do have falling action, namely stories with an Icarus arc.

According to a team of researchers at the University of Vermont, there are six primary story arcs. You can find the full list of story arcs and all their plot diagrams here.

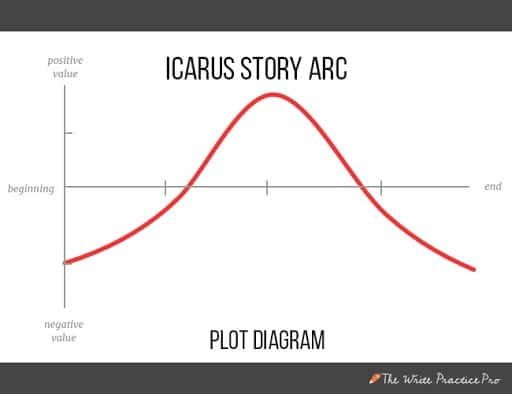

One of the six, the Icarus arc, is the quintessential tragic structure. See the diagram below.

It looks familiar, doesn't it?

In an Icarus arc, the character starts out in a really bad position, but as the story progresses, things get better and better until they reach a turning point, when there's a reversal and everything starts to go badly for the character until the story ends in a tragedy.

Sounds familiar too, right? Almost like Freytag's whole concept of story structure?

In this arc, there is a rise — you might call it a rising action — and then a fall — which you might call a falling action.

In other words, this is Freytag's pyramid. Freytag wasn't describing every story. He was describing this one specific arc.

It also means that the falling action isn't a plot element. It's a description of one section of one arc.

Useful, yes, but hardly universal.

Should You Use a Falling Action in Your Story Structure?

Now that we understand how the falling action actually works in a story (or not), should your story have one?

Unless you're writing an Icarus story arc tragedy, no, you shouldn't.

Can we just be honest with ourselves and say that while a resolution is a real thing, and an important part of the structure of stories, falling action doesn’t actually exist in most stories.

It's a helpful way to understand one particular story arc, but outside of that arc, it doesn't exist.

Falling action is not a universal element of plot. It's a helpful way to understand one section of one story arc, but that's it.[/share-quote]

What do you think? Is falling action a plot element? Should you use it in your story? Let me know in the comments.

PRACTICE

Let's put the falling action to use with a writing exercise. Here's a creative writing prompt to get us started:

Everything has been going well for your character. They've met the woman/man of their dreams, and even better, they're actually interested in them. They got a huge break in their career. And they just received a huge inheritance from a distant relative. Everything seems perfect, until . . .

Set a timer for fifteen minutes, and start writing about what happens in your character's falling action.

When your time is up, post your practice in the comments section to get feedback. And if you post, be sure to give feedback to at least three other writers.

Happy writing!

Joe Bunting is an author and the leader of The Write Practice community. He is also the author of the new book Crowdsourcing Paris, a real life adventure story set in France. It was a #1 New Release on Amazon. Follow him on Instagram (@jhbunting).

Want best-seller coaching? Book Joe here.

0 Comments