As a writer of fiction, you want readers to open your book and become so absorbed they can’t put it down. It helps to be aware that so much of what happens when a reader picks up a book takes place in the subconscious mind. Readers don’t realize that it’s happening, and many writers don’t pay attention to it either.

One of those largely subconscious mechanisms is story pacing.

Story pacing is often ignored as an aspect of learning how to craft a really great story. A lot of writers don’t give it much thought, yet it’s a critically important writing technique and quite exciting to learn about.

In this post, we’ll cover story pacing in detail, and I’ll provide some crucial areas for you to work on in your books—to open up some doors you didn’t even know existed.

Story Pacing Opened My Eyes

One of the primary ways we learn how to craft story is from reading a ton of books, especially in our target genre. I've been an avid reader of suspense fiction for as long as I can remember, and it's been a huge boost to my writing abilities.

So when I started writing thrillers, I felt fairly confident about my skills. I knew I had an exciting storyline, with intriguing plot points supported by well-developed characters and plenty of action.

That's why I was so surprised when my mentor took a look at one of my stories and said: “It's not a thriller.”

He told me I had all the right stuff for a thriller, but the pacing was off. After he showed me the same techniques that I'll share with you in this article, I was able to give the story a better sense of urgency, shaping it into a solid thriller.

With the help of this post, you can do the same with your stories.

What is Story Pacing?

You may be thinking that story pacing is simply the tempo at which your story unfolds. True enough, on the surface. But the deeper reality is that pacing is the art of keeping readers engaged in your story and not letting them out. It’s what pulls them through to the end.

Here’s another way to think about it. In a ThrillerFest panel discussion on the topic of pacing, Lee Child said:

“Every book you’ve ever read has a timeline; it starts somewhere and finishes somewhere. Pacing is how you manage that timeline.”

He goes on to talk about how he writes the slow parts fast and the fast parts slow. Meaning he operates like a photo editor reporting on a tidal wave. The editor shows the wave coming in at a tremendous pace and then slows down the tape as it crashes into the seawall to intensify the impact and examine it in greater detail.

As writers, we have the ability to speed and slow the rate at which our readers consume a story. You can learn those techniques and master the art of pacing by structuring your story according to genre.

Pacing is Inextricably Connected With Genre

Being clear about genre is really critical to the reader’s enjoyment of your story.

To make my point, I’ll tell you about this little trick my husband likes to pull on me. Sometimes when we stop at a gas station, he’ll disappear inside and come out with a large cup and offer me the straw. Though I never know what to expect, I can’t help but form some kind of preconceived anticipation.

So maybe I’m thinking root beer or Dr. Pepper. I take a drink and—Yuck! That’s awful! What is it? And he might say it’s Squirt. Well, I like Squirt, but since it’s not what my taste buds were expecting, it disappointed.

It’s the same with genre.

Readers start a story with certain expectations, they want a particular type of reading experience. That’s why genres exist. To help readers make good choices about what they want to read.

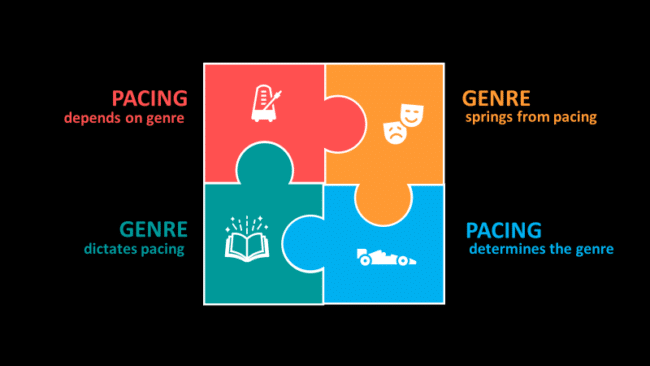

Pacing is dependent on genre and genre springs from pacing. Like the chicken and the egg, you can’t really separate them. The genre you choose to write will dictate the story pacing and the way you pace your book will determine the genre.

If a reader picks up a thriller and the story doesn't have fast pacing like a thriller should, they’ll put the book down or finish it in disgust and never go back to that writer’s work. Same with a cozy mystery or a slow-burn psychological suspense.

And the reader won’t even consciously register what was wrong with it. They’ll just know it disappointed.

Pacing in Mysteries, Thrillers, and Suspense

Let's think of a story's pacing like a theme park ride. When you visit a theme park, you know the kind of rides you want to experience. The ferris wheel is fun and so is the Tilt-a-Whirl, but they move at different paces. Story pacing is like that, too.

Use this analogy to take a closer look at how the pacing differs in thrillers, suspense stories, and mysteries. Each genre is a joy to read, but the experience each provides is unique.

Thrillers

Thrillers are roller coaster rides. You get in and strap down and then the coaster pulls slowly out of the station and starts chugging up that first hill. This is like character development, grounding the reader in the setting, and building the suspense.

By the time your reader is solidly inside the viewpoint character's head and has learned to care about that character, we've reached the top of that first big drop and we plummet ahead on a wild ride of twists and turns with an occasional breather while the story builds to another thrilling drop.

Thrillers are made of fast-paced scenes.

Mysteries

Mysteries are more like the funhouse. They're designed to surprise, challenge, and amuse with puzzles to solve and riddles to unravel. They're more interactive than a thrill ride, inviting readers to participate in working out the clues.

We may have to work our way through a revolving tunnel or cross a crazy obstacle course. And there may be spurts of fast-paced activity, but the overall tone of the ride doesn't have the frenetic qualities of a roller coaster.

Mysteries move at a moderate pace.

Suspense

We might liken suspense stories to the spooky rides where you ride on a track through a series of dark and mysterious passages, accompanied by scary music and lots of atmosphere.

Some of these rides are slow, drawing out the suspense, giving you time to worry and wonder about what's coming next. Other rides move more quickly, giving you less time to recover from the unexpected each time you turn the corner.

Suspense stories vary in pace and run the gamut.

Pacing Influences the Reader's Experience

As with most aspects of good fiction writing, intentional story pacing provides a quality reading experience. Proper pacing allows us to control what the reader thinks and feels. We do that in obvious ways, not so obvious ways, and some really subconscious ways. As I mentioned before, a lot of pacing is effectively a subconscious control system.

We’re going to look at the nuts and bolts of pacing, but unless you realize their purpose and understand the end goal, you won’t get full value from using these tools.

The way the page looks—sentence and paragraph structure, punctuation, amount of white space—sends signals to the reader about how to consume the story. Page appearance is important in pacing a book correctly.

So, before we dig into the specifics, we need to cover an absolutely key component of successful pacing.

Form Follows Content

If you’re wondering how to structure your sentences and paragraphs, look at your content. What’s going on in the story?

What is the character thinking or feeling in that moment? What should the reader be experiencing? These are what will tell you how long or short to make your sentences, paragraphs, and scenes.

In general, longer sentences promote slow-burn suspense while shorter sentences can create a frantic feeling of panic. But the number one rule to remember in story pacing is this: form must follow content.

This means that what's happening in the story should be reflected in the way it looks on the page.

If there's a fight scene, or some kind of fast-paced action going on, the sentences and paragraphs should be short, clipped, and surrounded by white space. If your character is arriving in a new setting and taking it in, these descriptive passages will be slower, with longer sentences and paragraphs.

Flashbacks also slow the pace as you pull the reader from the active voice of the story into a more introspective vein.

Ask yourself what's happening, and make your form fit your content.

Some people, when they hear the term pacing, think it means fast. And in suspense fiction, that’s often what readers want. But there’s nothing wrong with an occasional slow-paced scene if that's what the content calls for.

Good pacing is about choosing the appropriate speed to advance your reader through the plot. And that’s dictated by the genre, tone, and events of the story.

Feel free to throw out the rules of grammar if they get in the way of pacing and presenting the story. Fiction writing doesn’t always require full, grammatically correct sentences. Those rules exist to serve the story, and the story exists to serve the reader. Our job, as writers, is to serve the reader in the best way we know how. And sometimes that means breaking the rules.

Now let’s dive into the specific techniques used in pacing. We’ll look at four big ideas:

- Sentence structure

- Paragraph structure

- Scene and chapter structure

- Cliffhangers

Sentence Structure

The way you structure a scene’s sentences sends a message to the reader, usually on a subconscious level, about how fast to read. And the content of the scene will dictate the form.

Longer sentences, with lots of detail, tend to slow the pace and that’s perfect, if that’s what the content requires. Short, staccato sentences—even sentence fragments or single-word sentences with lots of white space in between—convey a fast pace. Machine gun dialogue—those terse conversations say, during a car chase—does the same thing. It speeds the pace.

Often, when there is physical movement in the story, the sentences will be shorter and when things are stationary, they’ll be longer. But that’s a generalization. Always base form on content. That’s really the only rule. Your job is to tell a story, and all the little pieces you use to do so should follow that story.

How pacing works in sentence structure

The energy of a sentence is in its kernel, subject + verb:

The woman screamed.

Sometimes you’ll need to include an object and indirect object:

The woman screamed obscenities at the burglar.

But keep in mind that any clauses you add will drain some of the energy:

The woman screamed obscenities at the burglar, cursing him for tracking mud on her Persian carpet, berating him for breaking the window.

Remember, that’s okay if it's called for by the content. What’s going on, and how do you want the reader to feel about it? Also, be aware of rhythm. In your sentence lengths and structure, you’re setting up a cadence which conveys a certain kind of tone.

The best way to learn the structures, rhythms, and cadences of well-written scenes is to read a lot and seriously study those who have mastered your genre's story pacing.

Action is content. If you're writing an action scene, you can often get away with less detail and shorter sentences. Content calls for them.

But two people sitting and talking doesn’t usually qualify as action. For moments like this, to keep the reader tucked into the story, you need to use more rich, sensory details that spark emotions and opinions. Which means longer sentences.

This doesn’t mean that if the pace of the story is fast you need to leave details out. Remember, you must tell the story—everything the reader needs to get the full experience. But if the pace is fast, you must deliver the information in a more clear, concise fashion.

No matter what the pace, you’ve got to get the reader inside the viewpoint character’s head, experiencing the story through that main character—their emotions, opinions, sensory input, and perception of what’s happening in the story.

Are you picking up on the major theme of pacing? Content drives everything.

Paragraph Structure

When a reader opens a book and sees a lot of black on the page—long blocks of text—that sends a message that it should be consumed at a leisurely pace. Short paragraphs with lots of white space around them signals a fast-moving page-turner.

It encourages fast reading.

The way you structure sentences and paragraphs will influence your reader’s breathing and physical state to some extent. Even when not reading out loud, we tend to breathe in conjunction with the words on the page, and faster breathing leads to a faster heart rate.

Lots of short, punchy paragraphs literally make your book a page-turner because your reader’s eye devours them and quickly moves on. Yet, in some cases, a long, run-on sentence can leave your reader breathless, since there’s no place to pause and take a breath.

Normally-paced text varies in paragraph length. It might go from a four-line paragraph to a three-line paragraph, then five lines followed by two, and so on. About ninety percent of most books, except for climactic scenes, run along in this sort of pattern. It’s interesting to the eye and doesn’t contain lengthy, intimidating paragraphs.

This will vary by genre. Literary works will tend toward longer paragraphs, while genres such as action adventure and thrillers contain only sixty to sixty-five percent “normal” story pacing. This utilizes a lot more white space and shorter sentences and paragraphs.

Use the power of the paragraph. Especially with faster-paced fiction. Hit the return key as often as necessary. Set short, punchy sentences apart for greater impact when the situation calls for it. This is a powerful technique.

How pacing works in paragraph structure

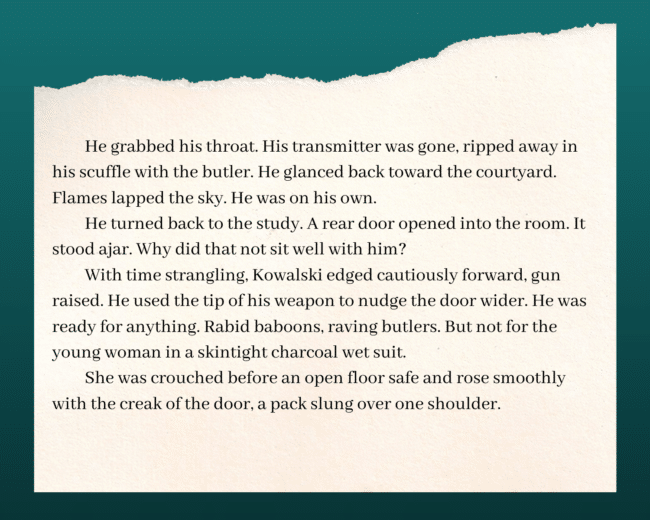

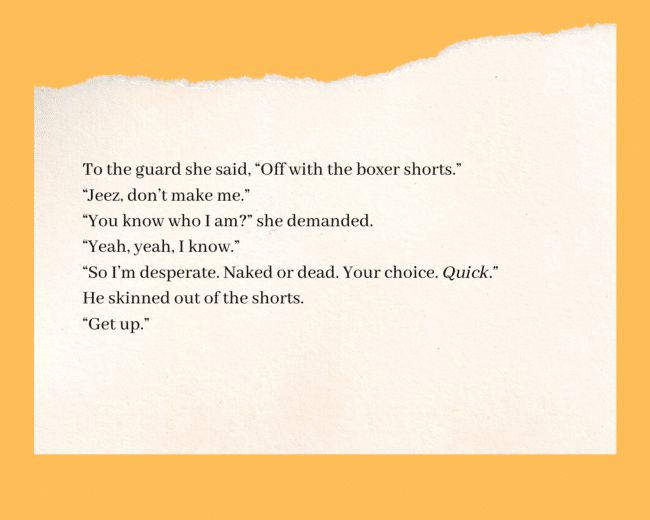

To further explore how paragraph structure affects reader experience, let’s take an excerpt from the thriller-paced short story Kowalski’s In Love by James Rollins. In this first example, I took the liberty of restructuring the paragraphs to reflect normal pacing:

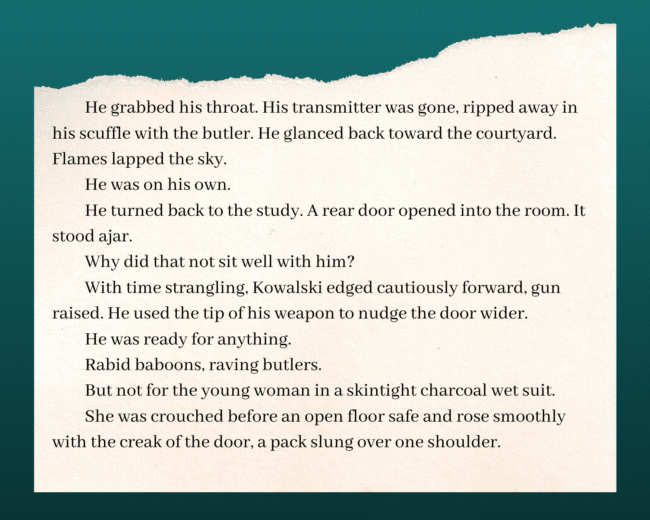

Now, see how it appeared in the published version:

Do you see how the shorter paragraphs facilitate a faster pace? Notice how they give more impact to the short sentences, which stand alone in their own paragraphs.

Scene and Chapter Structure

When you write, your scenes and chapters should drive the story forward and accomplish story objectives. Where you break them should not be random, but based on content.

You should be aware, however, that readers can bog down if the chapters are too long. Most readers are comfortable with chapter lengths between 2,000 and 2,500 words. Shawn Coyne, editor and author of The Story Grid, calls these “potato chip” chapters because they’re short enough to encourage readers to indulge in just one more before turning out the light.

And then, just one more…

It’s also useful to vary the lengths of your sentences, paragraphs, and scenes to avoid falling into a monotonous pattern. It’s important to realize that readers have an instinctive sense of story pacing, and when the pacing is congruent with the content, it feels right. If something is out of sync, they’ll sense that, too.

For example, years ago, when I read Connie Willis’s WWII time travel book, Blackout, I grew increasingly uncomfortable as I neared the end. Something was wrong. The pacing was off, and I realized my instincts were on target as the book came to an abrupt end—in the middle of the story.

The publishers had decided the book was too long and their solution was to chop it into two parts without any warning to the reader. I, along with thousands of other readers, was not pleased.

You want to do all you can to give readers confidence in your storytelling abilities. When they feel like they’re in good hands, readers will settle into a story and stick with it. Putting in the effort to get the pacing right will pay dividends in gaining reader trust.

Cliffhangers

Remember, the function of pacing is to pull the reader through the book to the very end. Cliffhangers are a vital part of that process and consist of scene and chapter endings and the openings that follow.

Cliffhangers don’t just occur at the end of a chapter where you decide to stop writing. They happen when you make the effort to build something compelling into that ending. Effective cliffhangers keep readers from putting the book down, bridge the gaps between chapters and scenes, and provide momentum.

Like links in a chain, the cliffhanger doesn’t stand alone. It connects to the next opening and incorporates techniques used in deep POV to ground the reader in the new setting and character, creating a seamless progression through the story.

For a detailed study on the crucial skill of writing cliffhangers, learn more from my post: Cliffhanger Meaning 101: What They Are and How Writers Use Them.

How Form Follows Content

Lots of factors enter into your reader’s experience with your book. Some of them are out of your control. Is she tired? Hungry? Just a had a fight with her husband? There’s nothing you can do about any of those things.

But you should do your best to take control of the things you can. Like the way your story looks on the page. This has a tremendous influence on your reader, though most of it happens on a subconscious level.

To get a better idea of what I mean, let’s look at an example from Dean Koontz’s thriller The Whispering Room:

Do you see how these terse, tight paragraphs of dialogue convey tension and move quickly like machine gun fire? This makes for a fast pace and the form follows what’s happening in the scene, a rapid back-and-forth conflict.

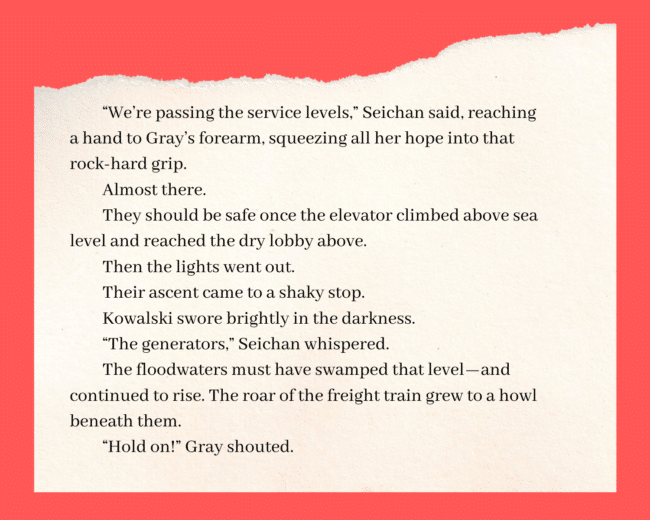

Now let’s examine another example, this one from Bloodline by James Rollins:

The concise sentences and paragraphs communicate tension to the reader and encourage a rapid reading, eating up the page, leading to faster page flips. They are direct and sparse, hiding nothing of the bleakness of the scene.

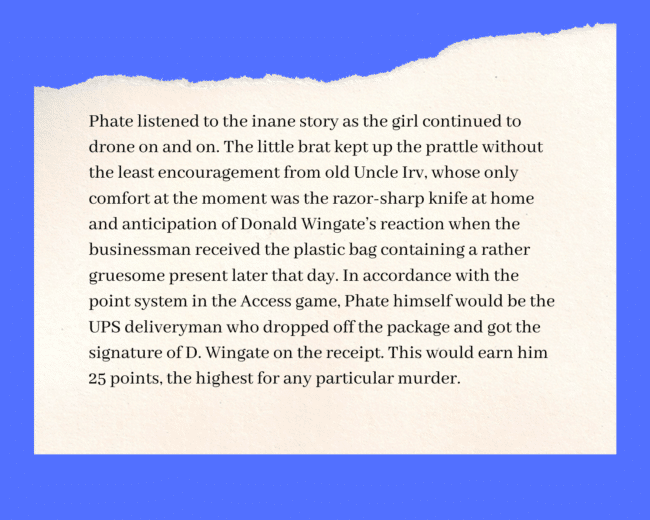

Here’s a contrasting example from Jeffery Deaver’s novel The Blue Nowhere:

Deaver could easily have broken this block into multiple paragraphs. Why didn’t he?

I think he did it this way because the long, unbroken paragraph mimics the droning on and on of the little girl. It also reflects the viewpoint character’s blasé attitude about murder, burying it in a pile of words as if it’s something of little significance, highlighting its trivial aspect as just part of a game.

Remember to think about what’s happening in the story and how you can use all your skills to communicate that to the reader. It’s not just the words you use, but how you arrange them on the page that affects the way your reader will experience the story.

Improving Your Story Pacing Skills

The first step in mastering pacing is awareness. Once you become aware of the subconscious signals you’re sending your readers, you can practice and improve.

However, the best way to control the pace of a story is from your own subconscious, the back brain, the creative part. Not from the critical front brain. So how does that happen?

It’s important to keep learning, studying, practicing, and polishing your skills as a writer. But to make those skills really useful, they need to be internalized and become a natural part of your writing process.

Musicians practice scales and fingering exercises. Basketball players run drills on passing, dribbling, and shooting. Dancers spend hours at the barre, practicing the basic moves. They do these things so that the techniques are available to them in concert, in the middle of a championship game, or on the stage.

We make muscle memory by repeating the proper movements until they become automatic.

For writers, this involves reading first for pleasure. And then, when you’ve found a book that grabbed you and pulled you all the way to the end, go back and study it.

Analyze and practice until you’ve internalized the skill and it becomes second nature. The first step is awareness, then comes practice. Do these things on a regular basis and eventually, the techniques and information will pass from the front of your brain into the back of your brain and become automatic.

How about you? Did you learn something new you can apply right now to your writing? Tell us about it in the comments.

PRACTICE

NOTE: DO NOT LET YOUR EYE TRAVEL DOWN TO THE ANSWER KEY. YOU'LL ONLY BE DEPRIVING YOURSELF OF A PRIME OPPORTUNITY TO LEARN

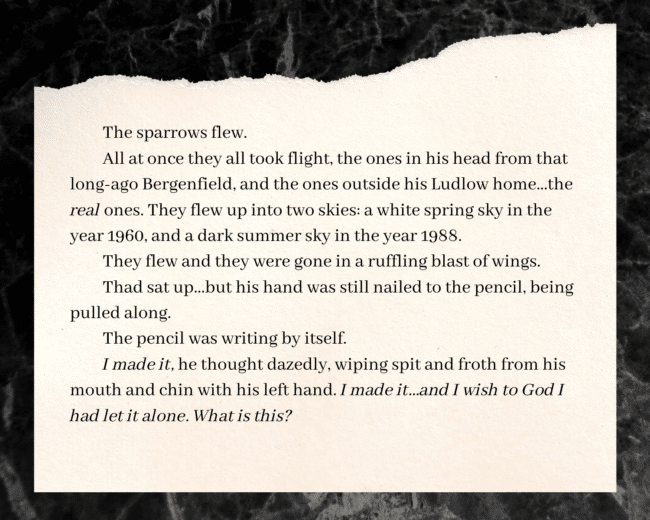

Let’s practice some story pacing skills! I’m giving you an excerpt from Stephen King’s book The Dark Half. I’ve removed the structure, punctuation, capitalization, and so forth.

Spend fifteen minutes reading the excerpt and then decide how to break it into sentences and paragraphs, punctuate, and capitalize. After you're done, take a look at how King did it. Compare your work to his and ask yourself why he did it the way he did.

Here’s the excerpt:

The sparrows flew all at once they all took flight the ones in his head from that long ago bergenfield and the ones outside his ludlow home the real ones they flew up into two skies a white spring sky in the year 1960 and a dark summer sky in the year 1988 they flew and they were gone in a ruffling blast of wings thad sat up but his hand was still nailed to the pencil being pulled along the pencil was writing by itself i made it he thought dazedly wiping spit and froth from his mouth and chin with his left hand i made it and i wish to god i had let it alone what is this.

ANSWER!

Here's King's passage:

Any day where she can send readers to the edge of their seats, prickling with suspense and chewing their fingernails to the nub, is a good day for Joslyn. Pick up her latest thriller, Staccato Passage, an explosive read that will keep you turning pages to the end. No Rest: 14 Tales of Chilling Suspense, Joslyn's collection of short suspense, is available for free at joslynchase.com.

Fantastic article — pacing is something I’ve struggled with, and you explained it here so clearly. I love how you broke down pacing into real, actionable parts (scene length, tension build‑up, knowing when to speed up or slow down). Your examples and reminders about emotional stakes really hit home. I feel more confident now to go back to my draft and examine whether scenes are dragging or sprinting too fast. Thanks for making something as slippery as pacing feel manageable!