Do you love a good cliffhanger? Most readers do. Whether they entail a twist that hits like a tidal wave or employ a more subtle revelation, cliffhangers keep readers eagerly turning the pages—even when they're unaware of a cliffhanger's meaning and function.

But what is the definition of cliffhanger? And how can we, as writers, master the use of cliffhangers to write a book that holds readers all the way to the very end?

In this article, we’ll dig deep into what a real cliffhanger is, what it does, and how you can create consistently potent cliffhangers in your own writing.

Cliffhangers Move Readers

You may think a cliffhanger is about setting up a situation fraught with action and danger, and that’s true on a basic level. But the anatomy of effective cliffhangers is more complex, more interesting, and more achievable than you may imagine.

Soap operas and television series make good use of cliffhangers to keep viewers glued to the screen and carry them through to the final episode. Writers can use similar techniques to capture readers.

Consider the oldest joke in the world, right:

Question: Why did the chicken cross the road?

Answer: To get to the other side.

That’s exactly what cliffhangers do for your readers. They move readers from the end of one chapter to the beginning of the next.

And they do it with rocket fuel.

But what if you launch your reader into the next chapter of your book without giving them a solid landing strip? You may have thrown them right out of your book.

Cliffhangers can create a perilous, hanging-by-a-fingernail chapter ending. But that's only half of the equation.

They can also be a lot more subtle, if you know how to do them right.

Cliffhanger Meaning: Definition and Purpose

Cliffhangers occur when writers do more than just stop writing at the end of a scene. They happen when the writer makes the effort to build something compelling into that chapter ending.

Cliffhangers are writing devices that serve three important purposes:

- They keep readers from putting the book down at the end of a chapter

- They hold the book together, creating bridges across the gaps between chapters

- They provide momentum, keeping readers moving forward to the end of the book

The function of a cliffhanger is to propel your reader along to the end of your story. So to be effective, you need a whole chain of cliffhangers. This is how the bestselling authors of genre fiction do it.

You can’t deliver a novel in one huge chunk. Few would start reading such a tome, and no one would finish it.

As readers, we need breaks, breathers, indications of progress as settings or characters change. That’s one reason we structure books into chapters and scenes.

The problem is that readers also see those scene or chapter breaks as a good place to stick a bookmark in it. Life is busy. Sometimes they don’t come back.

Correctly using both halves of the equation in an effective chain of cliffhangers will make your book hard to put down and spur readers to come back if they’re forced to stop reading.

The Formula for Great Cliffhangers

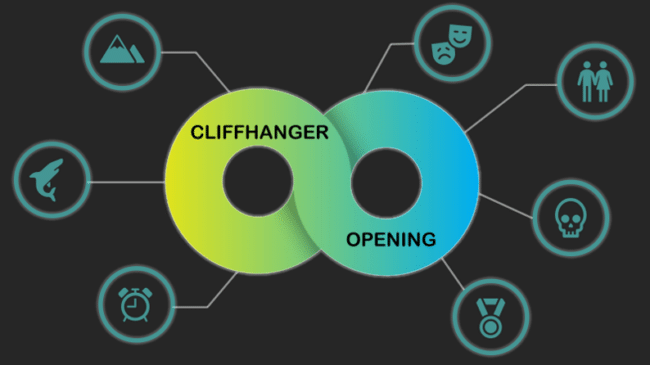

(1 Cliffhanger Ending + 1 Engaging Opening) x Chapters = A Book Readers Won't Put Down

The (Often) Forgotten Half of a Cliffhanger Equation

The obvious half of a cliffhanger is what everyone thinks about when they hear the term—a riveting chapter ending.

The other half is the opening of the next chapter.

These two halves must connect like two links in a chain:

Let’s explore this more, starting with the opening of a chapter.

2 Essentials After the Cliffhanger

The beginning of a scene or chapter after a cliffhanger must do two things well:

1. Continue the momentum

When you create momentum in your book, readers feel like something is always happening, driving the story forward. You want them to feel a sense of movement.

A cliffhanger is the ideal place to jump the story to a different character, setting, or timeline—this delays the outcome and keeps your reader in suspense. In most cases, you should take advantage of this and make a jump.

A story is woven of threads: character threads, setting threads, theme threads, plot threads, time threads.

In a multiple viewpoint novel, you’ll most likely jump to another character thread and pick up the storyline from a different POV. In a single viewpoint story, you may jump in time, setting, or theme. Because a story weaves threads, there’s always someplace for you to jump.

If you choose to stay in the same setting, with the same character, you must make the situation worse after the cliffhanger. Think of it like a television show that cuts to commercial just as your character falls into the frying pan. After the break, you need to tip him into the fire.

A perfect example of this is from Will Vinton's Christmas Claymations Santa Claus is Coming to Town. At one point, Chris Kringle is traveling through the forest when a group of eerie-looking trees seize him. Winter Warlock appears and tells Chris that he's disturbed him for the “very last time.” As he's held in the grip of the trees, Chris's eyes get super big as menacing music (dun, dun, dun) plays in the background. The scene fades to black, and . . .

Commercial break!

Did you feel the suspense? Viewers stay tuned to see what will happen to Chris after the break.

The cliffhanger sets up a suspenseful situation and builds the momentum up to a crucial moment before cutting the scene in half.

2. Ground the reader in the setting and POV character

Earlier in this blog series, we learned six types of key details that ground the viewer deep into the POV.

I cannot overstress the importance of this step. If you neglect it, jumping after the cliffhanger can bring readers to a jarring halt. How deep you go with the detail will depend on the pacing, and we’ll discuss that in a future article.

A rule of thumb is at least 200 to 300 words of pulling readers in with POV details in the scene and chapter openings of the first half of your book. As the pace picks up toward the climax, that will thin out and readers will be carried by the momentum.

But for that to happen, a story needs to hook a reader with POV early, and pull them in deep. This facilitates moving readers from one story thread to another without popping them out or giving them an easy exit.

Remember that when you’re opening a chapter, in many cases you are continuing on from a previous cliffhanger that occurred earlier in the book. In the meantime, you’ve taken your reader elsewhere, so it’s vital that you give them reminders and reground them in the setting and POV.

That's the opening of a scene. Now let's move to the first half of the cliffhanger, the scene ending.

5 Basic Scene-Ending Cliffhangers

We'll examine five basic areas for scene-ending cliffhangers, each with countless sub-categories limited only by your imagination. We'll touch on a few of them you can use to spark ideas for cliffhangers in your own stories.

These cliffhangers are:

- Physical

- Character

- Emotional

- Plot

- Thematic

Learn more about the five basic cliffhangers below, and study them deeply with examples of cliffhangers from bestselling authors.

1. Physical Cliffhangers

Physical cliffhangers imperil your character in some physical way, cutting at the height of tension. The classic example is a man hanging from a cliff while the villain stomps on his fingers.

Of course, there are hundreds of ways you could employ physical elements in a cliffhanger that don’t involve the edge of a cliff.

Be aware that you will layer the different types of cliffhangers for deeper impact. Watch for this in the examples ahead. You’ll better understand what I’m talking about as we introduce more cliffhanger types.

The Peril Cut

The peril cut puts the character in some kind of physical danger and then cuts the scene at the worst point.

Make sure, if there is any kind of lengthy setup that needs to happen, that you take care of it earlier in the scene.

When the pace picks up toward the cliffhanger, you need to be quick and to the point. Don’t immediately resolve the danger. Cut and jump, like we talked about before. Let your reader worry.

If you do stay in the setting, you must make the situation worse in the Opening.

Check out this example, from Michael Crichton’s book State of Fear:

Sarah stomped on the accelerator and the engine rumbled forward, but in the next moment the ground gave way completely beneath them, and their vehicle nosed down. Evans saw the blue-ice wall of a crevasse. Then the vehicle began to tumble forward, and they were encased for an instant in a world of eerie blue before they plunged onward into the blackness below.

CUT!

This cliffhanger is multi-layered. Layering cliffhangers gives them depth and greater impact.

The Blackout

Think of this like a fade to black on the screen. It can come about in a lot of ways—unconsciousness, sleep, even death.

The blackout nearly always involves a time jump. When you come back to this character’s viewpoint, you must account for that time. Let the reader know how much time has passed and how the character got out of the dilemma that caused the blackout.

You should cut and jump after the blackout, but don’t stay away too long. The farther they get from the scene, the less readers will remember or care about it.

This example is from Labyrinth by Kate Mosse.

Without warning, a rough and callused hand, reeking of ale, clamped itself over her mouth. She cried out as she felt a sudden, sharp blow on the back of her head and she fell.

It seemed to take a long time for her to reach the ground. Then there were hands crawling all over her, like rats in a cellar, until they found what they wanted.

“Aqui es.” Here it is.

It was the last thing Alais heard before the blackness closed over her.

CUT!

This is a prime example of a blackout cliffhanger, and you can be sure the author infused the wakeup scene with lots of sensory detail, emotion, and opinion to ground the reader in the next opening.

2. Character Cliffhangers

Character cliffhangers can tell us something new about a character, or piggyback off what we already know. Character cliffhangers and Emotional cliffhangers, which we'll talk about next, are the most common types of cliffhangers in the literary world.

Often subtle, character cliffhangers don’t always include a lot of fanfare, but done right, they are highly effective.

They work by cutting at the optimum point, continuing the momentum, and grounding the reader in the opening.

There are numerous sub-categories of character cliffhangers writers can use to accomplish this. We'll look at three of them.

Character reveal

This happens when the cliffhanger builds up and peaks by revealing something pertinent about the character.

Think about Indiana Jones at the end of the opening scene in Raiders of the Lost Ark. He’s just been through a dozen harrowing, life-threatening moments, but as he jumps into the getaway plane and it takes off, he freaks out about a little snake in his seat.

This shows us his fear of snakes, and we know it will come into play later in the story.

Here’s another example from Jeffery Deaver’s book The Blue Nowhere:

The guard left and the door slammed, leaving Gillette alone with his curiosity and itchy desire to get back to his circuit board. He sat shivering in the windowless room, which seemed to be less a place in the Real World than a scene from a computer game, one set in medieval times. This cell, he decided, was the chamber where the bodies of heretics broken on the rack were left to await the high executioner’s ax.

CUT!

This cliffhanger reveals that Gillette thinks in terms of computer games, particularly their more violent aspects. His computer expertise becomes important to the story.

Informational

This gives readers a piece of information about what’s going to happen, and should cut just at the point where the ramifications become clear.

This example is from Echo Park by Michael Connelly:

“Mr. Waits, fair warning,” O’Shea said. “If you make an attempt to run, these officers will shoot you down. Do you understand that?”

“Of course,” Waits said. “And they would do it gladly, I’m sure.”

“Then we understand each other. Lead the way.”

CUT!

This cliffhanger gets everyone—Mr. Waits, the POV character, Harry Bosch, and the reader—all on the same page about what’s likely to happen. It also reinforces the dire consequences of that action.

Tip to the reader

This type of cliffhanger gives readers a little something extra, a heads up about something the characters don’t know. It can heighten suspense or create dramatic irony.

Here’s an example from Clive Cussler’s Valhalla Rising.

“Don’t underestimate them,” said Burch. “Those guys are good. If anyone can ferret out the cause, they can.”

Pitt turned and smiled at Burch. “I hope you’re right, Skipper. I’m just glad it’s not on my shoulders.”

By the end of the week, Pitt would be proved wrong. Never would he have predicted that he would be the one called upon to solve the mystery.

CUT!

Notice how these cliffhangers are layered, combining elements from the different types. When you learn how to build both the blatant and the nuanced into your cliffhangers, you’ll hold readers spellbound, unable to put your book down.

Next up, the third type of basic cliffhangers.

3. Emotional Cliffhangers

Emotional cliffhangers involve some kind of emotion and a character's response to that emotion. Any emotion can form the basis for a cliffhanger—if the reader is deeply grounded in the POV character.

The emotion can manifest inside the main character, or be from another character and comprise the POV character’s reaction to the emotion. In some cases, it can even be directed at readers, designed to make them feel an emotion the characters are not experiencing.

These types of cliffhangers can be quite subtle and still be powerfully effective, but they must flow from a position of depth inside the viewpoint character. There is no limit to the number of sub-categories when it comes to emotional cliffhangers. They run the gamut of human emotion, but we’ll look at examples for three different sub-types.

Basic emotion

Any kind of emotion can be the vehicle for this kind of cliffhanger—fear, anticipation, dread, joy, uncertainty, grief, jealousy. The list is endless. Using emotion is often a great way to close a chapter.

Look at this cliffhanger based on anger from Echo Park.

Pratt stood up.

“Tell you what, talk amongst yourselves. I’m going over to the boathouse to take a leak. When I come back I’ll need an answer.”

Pratt walked past Anthony, coming close, each man holding the other’s eyes in a hard stare of hatred.

CUT!

Short and to the point, but it illustrates the concept well enough. Show the emotion and cut like a movie director, at a dramatic high mark.

Success or failure

Think of each character in a story as having their own character thread—with its ups and downs. Generally, when the protagonist is in a downswing, the villain is up. And vice versa. A great place to put a cliffhanger is right in the peak or valley of your viewpoint character’s swing, their success or failure.

Here’s another Echo Park example:

He was excited. A white van in a house where Raynard Waits had lived.

“That’s it!” he called out. “He has to be in there with the girl. Rachel, we gotta go!”

They got up and hurried to the elevator.

CUT!

This cliffhanger occurs when Bosch is in an upswing, just discovering the long sought-after location of his quarry. And it represents a downswing for the villain, who is—we presume—about to get caught.

Resonating remark

This is a highly effective cliffhanger, and one of the most common. It cuts the scene right after a character says something particularly significant, suggestive, or pertinent.

Look at this example from The Blue Nowhere:

“But . . .” Sobbing now, shoulders slumped in hopelessness. “Who are you? You don’t even know me. . . .”

“Not true, Lara,” he whispered, studying her anguish the way an imperious chess master examines his defeated opponent’s face. “I know everything about you. Everything in the world.”

CUT!

Such a cliffhanger leaves readers with a delicious sense of curiosity and prompts them to turn the page and continue reading.

In the next section, we’ll take a look at cliffhangers that arise from events inside the plot.

4. Plot Cliffhangers

Plot cliffhangers are triggered by events in the story.

The plot of a story consists of a chain of linked events, one leading to another in a cause and effect manner. These linked events often use a plot device to drive a cliffhanger, creating an ideal spot to cut and jump for maximum suspense.

You should remember, though, that the plot is not the story. The story is about theme and emotion, so plot cliffhangers tend to be thin unless layered with one or more of the other types of cliffhangers we’ve discussed.

We can’t begin to cover every plot cliffhanger here, but we’ll examine four types you can use as a springboard to create your own.

Leaping into the fray

This cliffhanger sets up a future chapter for high drama. Cut the scene just as the characters are stepping out to confront danger or looming disaster.

This example is from State of Fear:

The author suggested that the real news was the end of this long-term melting trend, and the first evidence of ice thickening. The author was hinting that this might be the first sign of the start of the next Ice Age.

The next Ice Age?

There was a knock on the door behind him. Sarah stuck her head in. “Kenner wants us,” she said. “He’s discovered something. Looks like we’re going out on the ice.”

CUT!

You’ll find many applications for this type of cliffhanger as you weave your stories.

A plan

In this cliffhanger, the characters are faced with a problem, maybe one they’ve struggled with through several chapters without success. And then someone gets a brainstorm. Cut the scene before revealing the plan. Make readers wait for it!

Look at State of Fear for a great example:

Kenner said, “Did you find a computer?”

“No,” she said. “There’s nothing there. Nothing at all. No sleeping bag, no food, no personal effects. Nothing but a bare tent. The guy’s gone.”

Kenner swore. “All right,” he said. “Now, listen carefully. Here’s what we are going to do.”

CUT!

In a subsequent chapter, when you pick up this thread again, you can either go into the details of the plan or simply take the reader along as the plan plays out.

Plot key

This kind of cliffhanger hits the spot and brings a burst of satisfaction. It occurs when a character finds a key piece of evidence or something else that moves the plot forward.

This example is from The Blue Nowhere:

Bishop’s phone rang and he took the call, He listened for a moment and, while he didn’t exactly smile, the cop’s face grew animated. He picked up a pen and paper and started taking notes. After five minutes of jotting he hung up and glanced at the team.

“We don’t have to call him Phate anymore. We’ve got his name.”

CUT!

The plot key cliffhanger scratches an itch and provides forward movement for the story.

Ticking clock

This type of cliffhanger reminds readers that time is growing short and imparts a sort of urgency to the proceedings.

Here’s an example from Valhalla Rising:

“Unless you can get the fire control systems operational in the next five minutes, this ship and everybody on it is doomed,” McFerrin shouted.

Sheffield was becoming disoriented now. All he could think about was: His career at sea was in jeopardy. If he made the wrong decision now . . .

And the seconds ticked away.

His inaction would ultimately cost over a hundred lives. CUT!

Reach for this dramatic cliffhanger as a handy way to add urgency and boost reader anticipation. Notice how, in this instance, it’s layered with a Tip to the Reader cliffhanger.

The last type of cliffhanger we’ll look at is Thematic. This one might be the most difficult to incorporate, but well worth the effort.

5. Thematic Cliffhangers

Thematic cliffhangers incorporate something that illuminates a theme in the story.

Theme is the powerful undercurrent that runs beneath the story, delivering a message to the reader through events, dialogue, imagery and symbolism, character behavior and consequences of choices made, and so on.

As a cliffhanger, it’s most effective to create a chapter ending early in the book which suggests failure in terms of the theme. Then, in one of the last chapters in the book, revisit the theme in another cliffhanger, showing progress and change. Or, in a tragedy, the lack of it.

Here’s an example of a thematic cliffhanger from Echo Park:

It was every detective’s nightmare. The worst-case scenario. A lead ignored or bungled, allowing something awful to be loose in the world. Something dark and evil, destroying life after life as it moved through the shadows. It was true that all detectives made mistakes and had to live with the regrets. But Bosch instinctively knew that this one was malignant. It would grow and grow inside until it darkened everything and he became the last victim, the last life destroyed.

He pulled out from the curb and into traffic to get air moving through the windows. He made a screeching U-turn and headed home.

CUT!

This cliffhanger hits on a deep level, hinting at the pervasive battle between good and evil and acknowledging that sometimes evil takes prisoners.

If you can tap into one of the universal themes of your chosen genre, your message will resonate with readers.

The Nature and Purpose of a Cliffhanger

Remember that a cliffhanger is more than just the place where you stopped writing at the end of a scene. Cliffhanging should provide a sense of movement, stir emotion, and keep readers turning pages all the way to the end of the book.

The most effective cliffhangers are multi-layered and are followed up by a powerfully engaging opening, employing deep POV details to ground readers in the next setting, character, or timeline.

Always read stories for pleasure first. But when you find a book that grabbed you and carried you all the way to the end, go back and study the cliffhangers the author used. Identify them by type, look at the openings that follow, sit down at your keyboard and type it. Get it into your fingers and your front brain, where the technique can work its way into your creative back brain and enrich your own work.

Cliffhangers bridge the gaps between the scenes and chapters in your book. They are important. Spend time working and studying, learning how to cliffhang effectively, and your books will pull readers all the way through from beginning to end!

Be sure to bookmark this page and refer to it often. Read the other articles in this series, too, in order to build a writer’s toolbox that goes way beyond a thesaurus or an English textbook, helping you master the art of suspense.

And don’t miss the next installment in this series—it’s all about pacing! An essential for any book containing effective suspense.

How about you? What’s your favorite kind of cliffhanger? Tell us about it in the comments.

PRACTICE

Consider the opening scene of your work in progress. Which type of cliffhanger from this post will serve your readers best? You might try writing multiple versions of the ending, using different cliffhangers to see which feels the most effective.

Once you've picked your cliffhanger type, write the ending to your first chapter for fifteen minutes. When you are finished, post your best choice in the comments if you’d like to share it. And please take a moment to provide feedback for your fellow writers!

Any day where she can send readers to the edge of their seats, prickling with suspense and chewing their fingernails to the nub, is a good day for Joslyn. Pick up her latest thriller, Staccato Passage, an explosive read that will keep you turning pages to the end. No Rest: 14 Tales of Chilling Suspense, Joslyn's collection of short suspense, is available for free at joslynchase.com.

0 Comments