Have you ever felt cheated when reading a book? Like the author held back information that would have enhanced your reading experience? Or neglected to include all the relevant details that would have allowed you to solve the mystery? Did the sequence of events in the story feel . . . off?

Think about this:

What if J.K. Rowling neglected to have Hagrid tell Harry about his parents’ deaths until the end of The Sorcerer’s Stone?

What if the writers of Die Hard had let Hans Gruber discover Holly was John McClane’s wife right up front?

What if Suzanne Collins had forgotten to alert readers to a rule change allowing tributes from the same district to win as a team in The Hunger Games?

Leaving out these vital pieces of information—or putting them in the wrong place—would have robbed these stories of a full measure of suspense, dulling the impact of their final scenes.

As a writer, you never want readers to feel cheated or disappointed by your book. But how can you make sure you include all the relevant pieces of the puzzle, in the correct order, to sustain suspense and satisfy your reader?

The Sequence of Events in a Story Makes a Difference

The chronological order of events in a story is not always the best way to deliver the information to the reader. I remember reading passages in William Faulkner’s A Rose for Emily in a college literature course. I felt struck by the way Faulkner moved his narrative around in time, creating a complex, multi-dimensional reading experience.

Faulkner was a master, and worthy of study, though I’d be leery about trying to imitate the advanced technique he used in A Rose for Emily. He began his narrative at the penultimate moment of the story—Emily’s funeral—and then used flashbacks, jumping back and forth in time, letting his viewpoint character relate the series of events until the final, revealing scene.

My main takeaway from this was that writers are unstuck in time, able to move around and present the events of a story to the reader in various ways. I became fascinated by the subject.

Since then, I’ve studied and experimented with various methods for delivering information to the reader.

In this article, I’ll share ways you can develop your own techniques for making sure your reader gets all the pieces of the puzzle, in optimal order, to achieve the effect you desire.

The Reader as an Active Participant

Readers get the most satisfaction from reading a story when they are engaged as active participants. Many factors go into making this happen.

One of the most critical components is information flow—when a writer delivers everything the reader needs to know, in a timely fashion.

Given the right information, at the right time, readers should be able to follow the rising action, gauge significance, and predict possible outcomes, letting them interact with story events and characters in a real way. This is important, whether you're telling a joke, restyling a fairy tale, or writing a complex novel.

An effective flow of information allows readers to forget they’re reading, and just be inside the story. Because everything they need is delivered just as they need it, nothing boots them out of the fictive experience.

It’s imperative to establish depth, characterizing scene and setting from inside your viewpoint character’s head, rather than describing from an external perspective. Also, make sure you engage your reader’s emotions with a main character they can support and something crucial at stake.

You might think of these steps like fastening the seatbelt that straps readers in and prepares them for the twists and turns ahead.

Let’s take a look at how sequencing events in a story will allow you to engage the three modalities that entertain readers and move the story forward.

Before A Sequence Comes a Scene

Before we get into the sequence of events in a story, however, it's worth taking a pause to review what a scene is. In order for story structures to work, writers need to learn the craft of writing a scene.

Once they can do this, they strengthen their skill of sequencing scenes in order to form acts, or other units of story.

A logical sequence will engage the reader, and this endeavor works even better when each scene holds a reader's attention with equal interest.

In this video, you can learn more about what makes a great scene and how to write your own.

Suspense, Surprise, and Curiosity

How a writer orders the events in a scene can determine a reader's response to the story.

There are three main responses a reader could feel: suspense, surprise, or curiosity. Let’s examine this by changing around the order of the following four events in a scene:

- Darren cuts the brake line on Flora’s car.

- Flora leaves the house and climbs into her car.

- Flora starts the car and steers it down the mountain pass.

- Flora’s car jumps the guard rail and she crashes to her death.

Suspense depends upon providing something for the reader to worry about and delaying the outcome, giving them time to agonize and anticipate. So, one way you might order events to foster suspense is to go right down the list, events one to four.

As readers, we see Darren tamper with the brake line and we feel Flora’s peril as she leaves the house and gets into the car, unaware of what awaits her. As she starts down the mountain pass, our worry and anticipation grow. What will happen? Will she find a way to stop the car from careening over a cliff? Right up until the moment the car plummets over the edge, we wonder if she’ll throw herself clear or stop the car somehow.

If you’re going for surprise, however, a better presentation would start with the second event.

We see Flora leave the house and drive down the mountain. We’re surprised when the car picks up speed, veering out of control, and Flora discovers the brakes don’t work.

Depending on how long you give Flora to wrestle with the car, we either don’t have time to prepare for the shock as Flora sails over the cliff, or we get a little buildup of suspense as we hope she finds a way to save herself. Either way, the story situation resolves when the information in the first event is revealed to the reader.

On the other hand, you could leverage curiosity by starting with the fourth event.

We see Flora’s car crash and explode into a fiery ball. We ask why did this happen? Was it an accident or murder? Who is responsible? How did they accomplish it? A reader's curiosity rises and carries them forward while suspense blossoms as the answers—revealed in events one, two, and three—are delayed.

It’s a good idea to incorporate a few surprises into your story, and to use curiosity to perk questions in your reader. But suspense makes the best mainstay. The anticipation of danger is more emotionally involving than the danger itself.

Sudden violence electrifies but can’t sustain an emotional effect and diminishes with repetition and duration. Curiosity will waver, if it's not backed up by suspense. These three modalities together make a great team, but let suspense be the primary driving force in your story.

Whichever you choose as your main modality for handling each scene, suspense will play into it as readers receive information and use it to formulate predictions about what will happen next.

Don’t Withhold Important Information

Lisa Cron’s book Wired for Story, is structured on a Myth/Reality basis. Here’s one of the Myths she puts forth:

Withholding information for the Big Reveal is what keeps readers hooked.

And here’s the Reality:

Withholding information very often robs the story of what really hooks readers.

She follows up by warning, “If we don’t know there’s intrigue afoot, then there is no intrigue afoot.”

To get a better idea of what this means, let’s try an experiment.

First, I’ll sketch out a scene where I’ve withheld some information, thinking to better surprise my reader with it later:

Gerald visits a used car dealership and checks out several models. He chooses an old Mustang, but the slick dealer tries to interest him in a Corvette.

Finally, the reluctant dealer lets Gerald take the wheel of the Mustang as they go out for a test drive.

Gerald is not impressed. The car makes a knocking sound and rides lower on the chassis than it should. He thinks about taking a second look—popping the hood, checking out the trunk—but decides it’s not worth his time.

The piece of information I kept from the reader is that the dealer has kidnapped a woman and has her gagged and bound in the trunk of the Mustang. He's ready to transport her when his workday ends.

By withholding that information until the end of the scene, I could get a decent cliffhanger with a surprise effect. I could have the dealer wait until Gerald leaves and then open the trunk to show the frightened woman inside. Not bad.

But, I think I can get more mileage out of it—and more suspense—by letting the reader know about the victim beforehand.

That way, every nuance during the sales talk, every bump on the test drive, and that moment when Gerald thinks about opening up the trunk are rife with suspense, leading the reader to anticipate possible outcomes.

The Standard Murder Mystery

As writers, we get to choose which events to include, and how to order them. In a standard murder mystery, the main events might unfold like this:

- Something happens to give the murderer a motive

- Murderer makes a plan and obtains a weapon

- Murderer kills the victim

- Someone discovers the body

- The detective arrives on the scene and starts gathering clues

- The detective interprets clues and expands his investigation

- The detective solves the crime

Writers can present events in that order, but it’s often more interesting to mix them up. Choosing to reveal the origin of the motive toward the end of the story will build suspense and keep the reader guessing about the “why” of the crime.

It’s intriguing how past events have devastating, far-reaching effects, and the anticipation of discovering that precipitating event grips readers.

Two Exercises to Study Sequence of Events in a Story

Let's look at two exercises that will help you understand more about how to order events in a story to achieve the effect you want.

One of the exercises—the study of chronology versus presentation—examines the overall big picture.

The other exercise—dealing with the flow of details—focuses on the micro view.

1. Chronology Columns Exercise

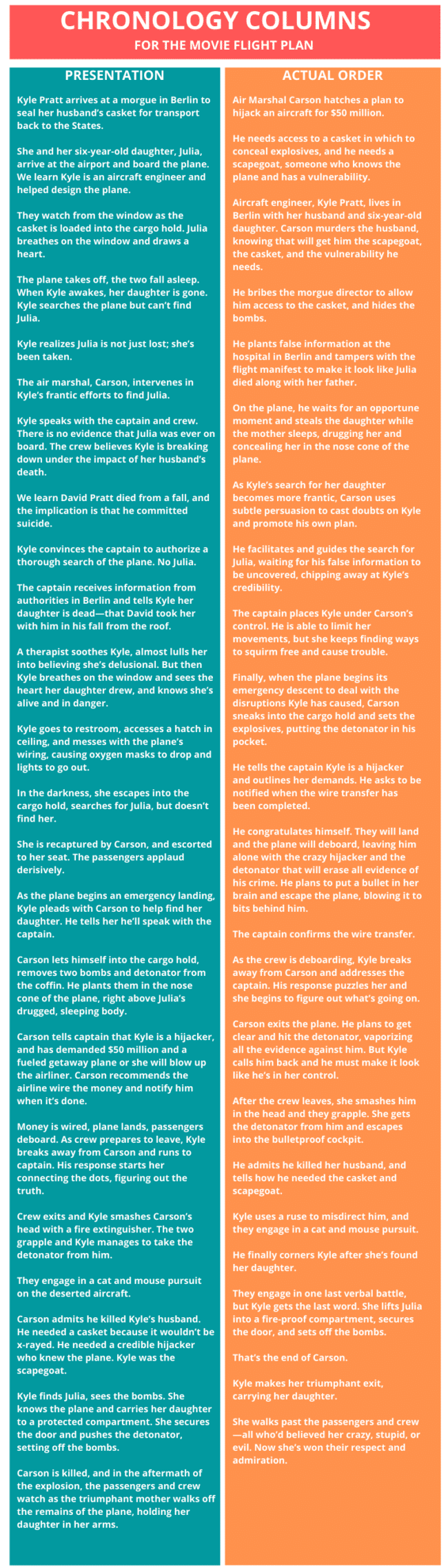

One way to determine the roots of a crime and study how events are ordered to create suspense and maximum dramatic effect, is to use a Chronology Columns exercise. This will help you understand how authors presented events to their readers in the stories you admire.

- Start by creating a worksheet with two columns. This will serve as a kind of graphic organizer.

- Enter events into the left-hand column as the author presented them in the story. In the right-hand column, order events as they really happened.

- Last, study the interplay between the two columns.

As an example, let’s do a basic Chronology Column exercise for the movie Flight Plan.

I chose Flight Plan because the events in the story appear so unconnected and perplexing, yet when you understand the impetus behind them, the inexplicable makes sense. It's interesting to see how that is accomplished.

MAJOR SPOILER ALERT!

Flight Plan Case Study Exercise One: Chronology Columns

Here is a graphic that shows the sequence of events in the story Flight Plan—the order in which they were presented to the viewer, versus the order in which they actually happened.

The death of Kyle's husband made no sense to her. She hadn't seen signs that indicated he might take his own life. While in that bereaved and baffled state, her daughter is taken from her as well, further battering her, emotionally.

Viewers, along with Kyle, try to figure out what's really going on, based upon the information that comes to light. That delivery of clues leads us down a path to thinking Kyle must be delusional. But when she breathes on the window and sees her daughter's heart, we know we must search for answers in a new direction.

The big reveal comes when Carson rips out the lining of the coffin, exposing the bombs. That starts a rapid piecing together of events that takes us on a breathtaking ride to the finish line.

Do you see how the writers arranged events to capitalize on suspense? They used all three modalities—surprise when Julia disappears, curiosity when we wonder what happened to her, and suspense as the layers unfold and the outcome is delayed.

Do you see how you might order the events in your story to achieve a similar effect? Take some time to study stories you found captivating, retell them, analyze them with this exercise, to see how the author presented events versus their chronological order.

2. Micro View of Details Exercise

We’ve examined the big picture of how events were laid out in the movie Flight Plan. But there’s more to effective information flow than the order of operations. Within each event, each scene, you need to be constantly shepherding the story elements, delivering relevant information and raising new questions to give readers what they need to actively participate in the story.

As an exercise, try watching the opening of a movie and detailing the sequence of events to see what you learn from it. I’ve done this with Die Hard, Back to The Future, The Sixth Sense, Raiders of The Lost Ark, The Terminator, and Flight Plan.

To show what I mean, let’s walk through the opening scenes of Flight Plan to see how it gives viewers what they need in order to predict and anticipate outcomes.

Flight Plan Case Study Exercise Two: Micro View of Details

The movie opens with Kyle Pratt sitting alone on a Berlin metro platform. Her frozen stance and the look on her face tell us she’s terrified, wrestling with some great trauma. Curiosity grabs us as we begin to wonder what it is.

Her husband arrives, and she takes his hand, but the distant point of view and camera angles make it feel weird. We suspect all is not as it seems and wonder what’s going on.

She arrives, alone again, at the morgue. The director escorts her to an open coffin, and we see her husband’s body laid out. We understand he was killed in a fall when the director apologizes, explaining there had been some damage to his head. He instructs Kyle to enter an electronic code, sealing the casket for transport, and we know she'll be accompanying his body back home.

As Kyle leaves the morgue, she is again joined by her husband, and we understand that he appears only in her imagination, helping her to cope with losing him and being alone in a foreign country during this time of distress. We wonder about the circumstances of his death and what will happen next.

They walk home together, and she asks him if they can sit in the courtyard. As she clears snow from the bench, blackbirds fly and she looks up to the roof. We imagine that’s where he fell to his death.

In the apartment, she lies in bed with her young daughter, soothing and reassuring her, closing the drapes against strangers who might intrude. We feel her maternal instinct to love and protect.

The apartment is bare, everything packed into boxes. There is a bleak, bereft feeling. Kyle takes some pills. We understand they’re some kind of prescription to help her through. We get a glimpse of her employee badge and know she works for Elgin Aircraft.

As the scenes unfold, little things reveal important bits of information and raise questions so we’ll continue watching to find more bits of information. Delivering those bits on the right timeline and in the right order is what keeps us absorbed in the story.

You can do the same thing with your story, using these two exercises—the Chronology Columns and the Micro View of Details—to help you study and structure events to create the effect you want. Or troubleshoot a scene that isn’t working. Or simply learn from the masters.

More Ways Than One

Suspense works best when you set up multiple possibilities for your character. The reader needs to be able to identify more than one potential outcome, ideally at least one positive and one negative. Worry increases when the negative outcome seems the more likely, especially as you raise the stakes, increasing the odds against your hero.

Readers are hardwired to predict what’s going to happen in a story, and they revise their theories as the story progresses. As writers, we have the power to disclose information in a way that will guide their predictions in a particular direction.

We can make it look like the undesired outcome is more liable to happen. At the same time, we make it difficult to imagine how the desired outcome could ever be achieved. We do this by the way we deliver information, using foreshadowing and well-planted setups so that the eventual outcome feels natural and logical.

In future articles, we’ll take a closer look at how to use foreshadowing, clues, red herrings, and other devices to enhance story sequence and direct the reader’s attention where we want it.

Suspense, the Renewable Resource

There is an emotional factor in anticipating an outcome—either dread or excitement. That’s what makes it possible for us to read, watch, or listen to the retelling of a story more than once and again enjoy it. The elements of suspense are still at work, sparking the emotions of anticipation, because the reader is an active participant.

Whether you're working on a short story, a novel, or anything in between, when you build your writer’s toolbox by studying and practicing the common core of skills you’ve learned from this series of articles, you become empowered to create great stories packed with suspense. Something that will thrill readers and keep them coming back for more.

I encourage you to try the two exercises I outlined in this article: Chronology Columns and Micro View of Details.

Not only will you learn a lot, but you’ll be training your writer’s brain to deliver information to your reader in effective ways, honing your sequencing skills.

Be sure to bookmark this page and stay tuned! The next article is all about cliffhangers—you don’t want to miss it!

Do you use the sequence of events in a story to engage a specific emotion in the reader? How do you do this? Let us know in the comments.

PRACTICE

Let’s focus on the sequencing activities in your opening. Using the story idea and character you’ve developed for the book you’re writing in conjunction with this series, think about the micro flow of details you’re supplying readers from the beginning.

Are you anticipating your reader’s needs? What details must they have at this point in the story to keep them turning pages? What should you tell them to raise questions now and promise answers down the road?

Read aloud. It helps you come at your own work from a reader's perspective.

Spend fifteen minutes writing this opening.

When you're done, examine the opening and revise as necessary to provide a clear and compelling flow of information. When you are finished, if you want to, you may post your work in the Pro Practice Workshop.

Don’t forget to give your fellow writers some feedback and encouragement!

Any day where she can send readers to the edge of their seats, prickling with suspense and chewing their fingernails to the nub, is a good day for Joslyn. Pick up her latest thriller, Staccato Passage, an explosive read that will keep you turning pages to the end. No Rest: 14 Tales of Chilling Suspense, Joslyn's collection of short suspense, is available for free at joslynchase.com.

![How to Write a Scene [Novel Writing Coaching]](https://thewritepractice.com/wp-content/cache/flying-press/379f78ed33ef4d6e2f67d4cde74796d9.jpg)

0 Comments