What should be included in your first draft? Writing the first draft of a book is incredibly difficult. So much so that you don't even finish their first draft. Why is this? And how can we prevent this from stopping us from writing our first drafts?

Every writer who has ever written a book wrote a first draft for that story—and it's highly unlikely that the first draft was also the final draft.

Of course, it's hard to remember this when you're reading a published book. Writers don't often see the first, or even second (maybe more!) drafts of a book. Just the final product.

However, behind every great story there is a beginning—and in every beginning there are elements we, as writers, need to care about accomplishing. There are also elements that will only hold us back.

In this post, I will cover the three elements you need to include in your first draft, and the three elements that will only slow down or stop your writing process.

A Story is Ugly Before It is Made Beautiful

Writers are all perfectionists underneath.

Have you ever sat down at your desk to start a book and found yourself dreaming of the perfect, final project? Do you see it shiny and bound, sitting on the shelves of your favorite bookstore? You've probably imagined bringing that book to life, writing it out in all its glory. I'm sure you've dreamed of it hitting the stores.

I have some news for you—that perfect book is not the book you’ll be writing.

Not yet.

You see, there is a misconception, especially in new writers, that the book of your hopes and dreams is the one that will materialize when you write.

Often this dream is dashed quickly when a writer starts putting pen to paper (or fingers to keyboard) and realizes the story isn’t going quite as they envisioned. Maybe those dramatic scenes are coming out dry and dull. Maybe the beautiful language that came to them in the shower turns out to be stilted and awkward.

This, as you can imagine, can be pretty discouraging.

However, it doesn't need to be that way. Many new writers have walked away from perfectly promising books because that first draft didn’t magically turn into the perfect best seller they wanted. But the truth of the matter is, the first draft was never meant to be the final project.

The first draft is just that—a first draft. The initial attempt, the ugly before the beautiful.

The stepping stone that brings you closer to that shining manuscript.

In this post, we are going to take a look at three things you should expect to accomplish in your first draft—and three things you shouldn’t. All of this will help you complete your first draft fast, so that you can start working on the revisions that will make it what it needs to be before you burn out.

What is a First Draft? A Visual Example

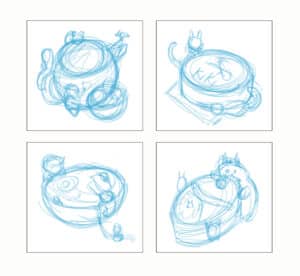

Before we get started, I’d like to show you something. A few years ago I participated in a Studio Ghibli themed art show at a small art shop/gallery. It was a lot of work but great fun. Here they are hanging on the gallery wall:

I was very proud of how these pieces turned out. They looked great and received quite a few compliments. I even sold three of the four pieces at the show.

While that didn’t amount to any significant profit, I was still glad to be able to claim I was an artist who has sold art. However, what you see here is the final product, the equivalent of a shiny new book on the shelf. A few weeks before the show, they looked like this:

As you can see, there are nothing here but general shapes and ideas. The arrangement of the four pieces weren’t even in the same order I wound up putting them in because I originally thought the large shapes could sit in a diamond formation.

Two of them eventually wound up being flipped to mirror image versions. I had no idea what the color scheme would be at this point and wasn’t even sure these were the four designs I would stick with.

From this rough image, you can sort of glimpse an idea of what the final product could be, but with only the basic essential elements intact. It offers a glimpse of the final version, but by the end of the process, it could look completely different.

That, my friends, is a first draft of a manuscript.

You might have a plan—but that initial idea might change, even if the skeleton of the story remains constant.

But how do you know when you've written a solid first draft? What should a first draft accomplish, and what should be included in a first draft to do this? These three elements.

3 Elements You Should Include in Your First Draft

Now that we understand what a first draft should be, let’s look at what you should really aim to accomplish when writing one. To do this, we can distill your first draft goals down to three basic elements.

1. Tell the Story

The most important accomplishment for your first draft is that it tells your story. A story should have a clear beginning, middle, and end.

Three main ideas that illustrate a plot-effective beginning, middle, and end include:

- Beginning: You know how and why the protagonist is called on some sort of adventure (or there is an inciting incident in the beginning of the book)

- Middle: There are conflicts that challenge the protagonist in the middle of the book (and these raise the story's stakes)

- End: There is a climatic moment in the end of the book that shows how the protagonist gets or fails to get their object of desire—or their wants and needs—by the end of the book

To put it simply, get you from point A to point B.

Structure matters more than beautiful language. Even if you wrote your first draft entirely in short, simple sentences like “See Jane run,” finishing a first draft that moves a beginning, middle, and end with plot events that cause a character to make decisions—which raise the stakes—is a success.

A simple way to do this is by creating an event list for each of your books. Start with one major event each, then distill down to smaller events. For example, round one could be as simple as:

Beginning: Hero, who thought she was always a peasant, finds out she was actually a hidden royal.

Middle: Hero goes through the difficult process to prove her royalty to the rest of the royal family in order to gain power and make life better for the poor.

End: Through a brilliant move, she is able to prove her identity and the queen accepts her as a true royal.

Notice this list does not include any kind of detail. There's nothing about how the hero rounds out about her identity, what the challenges she faces are, or how she finally proves herself. However, as a first step, this is enough.

Once you've made a basic plot list like this, you can go back and add to the events in each section. For example:

Beginning: Hero is a farmer. Her parents' friends, other farmers, often complain about taxes. Hero notices her parents do not seem to complain.

One day, she overhears her parents talk about the fact that they are grateful they don't pay taxes. Hero is confused. Hero digs further.

Hero finds out someone in the royal family is excusing her parents from taxes as reward for her parents helping raise her in secret.

Now you have a more detailed list of events.

You can delve even further on these tasks, and we will cover this process in more detail in the future, when we talk about first stage planning. But for now, think of this as the “rough sketch” that lays under your finished book. It's only a simple list, but without it, there is no way of moving forward.

There is no way around a first, rough draft. It's okay if you don't know all the “perfect” details yet.

2. Establish the Tone

Tone is something that is difficult to plan. You can make all the scene lists (a topic we will cover later) and character bios you want, but once you start writing, the story often takes on a life of its own.

Perhaps what started out as melancholy becomes irony, tragedy becomes comedy, light and funny becomes dark and moody, and a cowardly character suddenly finds the strength to become brave.

A good way to identify what the tone of your book is is to observe how your characters react to tense situations and challenges. For example, let's say our main character's love interest has found a new lover. What is your MC's reaction to this news?

If their instinct is to go home, lock themselves up, weep, and stare out at the rain, the tone of your book might be dramatic and tragic.

By contrast, if their instinct is to go get a revenge makover and end up dying their hair a funny color, which they then try to pass off with feigned confidence, then your tone might be a comedic one.

Without the physical act of writing the book down, you will never quite grasp what the tone of it will be. This is a major reason that it is unreasonable and unrealistic to expect to write a first draft that’s publish-perfect.

Much like a theme, by simply telling your story from beginning to end, you will find the tone you want to strike in future drafts.

3. Get to Know Your Characters

There’s no better way to know your character than with that first draft.

Trying to get to know your character through a pre-written bio sheet versus writing the first draft is like trying to know someone by looking at their Facebook profile instead of taking a long, adventurous trip with them. You can only get to know someone so much by looking at a list of facts.

However, when you travel alongside a friend—even one you don't know well before the trip (especially this kind of friend)—you will learn how they live, what they eat, how they celebrate their achievements, how they mourn their loss, how reliable they are, and how they react in times of danger.

The same goes for learning more about your characters when writing your first draft.

I learned this lesson when creating Donna “Astra” Ching, the protagonist of my upcoming novel Headspace.

I went into the first draft with an image of her as a competent, independent young professional being in complete charge of her life. She had bought and set up a lovely new house, was doing well in her field of work, and excited to start her new life.

The story opened in her living room, which she had just finished cleaning and decorating.

But as I kept writing, I realized this was not quite who Astra was. She was certainly competent and independent, but this neat, primped lifestyle wasn’t her. She enjoyed privacy and comfort, and her comfort didn’t necessarily come from a Martha Stewart-style home.

By the end of the book, Astra had become a slightly different person.

She became someone who was comfortable with her messy home, who prioritized setting up her library while the rest of her house went neglected in the chaos of moving, and who made well-meaning to-do lists in her head, most of which she still hasn’t gotten to by the end of the book.

Want to get to know Astra and her organized chaos? Headspace will be published in July 2021, but you can read it now for free when you join my launch team! Send an email to admin@thewritepractice.com to let me know you're in.

Want to get to know Astra and her organized chaos? Headspace will be published in July 2021, but you can read it now for free when you join my launch team! Send an email to admin@thewritepractice.com to let me know you're in.Looking back on it, Astra’s characterization was off by quite a bit in the first draft. But without writing the first draft, I never would’ve gotten to know her well enough to properly tell her story.

All this to say, the more time you spend with your characters, the more you'll learn about them. This means you probably don't need to burn time outlining every detail of your entire cast before writing, and even if you do, some of these details might change as you write your book.

As you write, try asking yourself these questions:

- Is the way this characters acts realistic? In my case, it seemed that while some 20-something-year-olds could set up a new house neatly as soon as they moved in, most are probably OK with leaving it a mess for a while.

- Is the way this character acts relatable? Same as the answer above—by giving herself some leeway on her organization, Astra is a more relatable young woman.

- Is this character acting this way out of instinct or out of some sort of social or perceived obligation? The neat home felt more like an unrealistic expectation, and Astra was not one who catered to expectations.

- Does it make me happy to write the character this way? I was much happier to see Astra rearranging her neat little library while the rest of house laid in disarray, as it's something I and a number of people close to me would do.

- Is this behavior consistent with how the character makes decisions for the rest of the story? Astra does not care for the expectation of others and did what she felt was right for her. This carries on through the rest of the book.

It can feel scary to dive into the story and hope your characters unfold with it, but this might be the exact conversation starter you need to really get to know them.

3 Things Not To Worry About in Your First Draft

Believe it or not, it’s equally important to understand elements you shouldn’t focus on in your first draft. Trying to achieve these elements will only frustrate you and lead you to believe your story will never be as good as you imagined it. You'll get ahead of yourself in the writing process, and because of this you might suffer low self esteem or burnout.

Let’s take a look at what not to do so you do finish your first draft.

Mainly, this includes letting go of three “perfect” elements in your story:

1. Language and Detail

The first draft is not where you should try to exercise your inner Shakespeare. This is not the time or place for you to write beautiful sentences, use big words, or experiment with flowery language.

Remember, the goal of the first draft is to tell your story, and excessive attention to pretty words will only distract and frustrate you, especially since a lot of it will likely be cut in the editing and rewriting process.

If you find yourself struggling with a sentence as you write, ask yourself—does this sentence progress the story or develop a character?

If it does, write it down as simply as you can.

For example:

John lost his father's watch which was the only thing left from when his father was in the war.

This is enough to explain the importance of the watch without going into any in-depth description of what kind of watch it was, which war his father fought in, or how he lost it. These details can be explored in future, in vivid scenes and beautiful details.

If you find you are trying to fill out an intricate detail, such as which kind of watch was used by soldiers during WWII when writing a first draft, chances are it's not something you need to write.

2. Character Development

This may sound strange because I just said that the first draft is the place to get to know your character, but hear me out: you need to get to know your characters. You don’t need to force their development.

To avoid obsessing over this, write the story and let it go where it may. By doing this, you are more likely to develop your characters based on your instincts rather than tick off boxes you feel they should fill.

Don’t try to force your characters to develop a certain way or force certain personality traits or back stories. Let's go back to the example of your character's love interest having found a new lover to understand why.

Considering this example, perhaps you initially intended for them to have a lonely episode of mourning with a bottle of vodka, but as they approach the liquor store, you felt like there's a nightclub next door they'd rather go into. Follow that instinct and see where it takes you.

If the scene doesn't work out, you can always backtrack to the liquor store later.

Overall, the first draft is where your characters should be free to lead. Allow yourself to be free and explore where your characters take you.

Rather than trying to stuff your characters into a box, write the story you want to write—even if some details turn out to be wild and self-indulgent.

Don't be afraid to ask a character what they really want.

And if they give you an answer, don't be afraid to listen.

3. Fixing Plot Holes

Why shouldn't you focus on fixing plot holes in the first draft? Because plugging plot holes can be frustrating, and the effort that goes into them can really derail a train of thought when you’re on a roll.

Imagine you’re writing a big, action-packed scene, your heroes are running from their enemies toward their ship when suddenly a huge chasm appears in the ground. They’re running and running—but how do they get across?

How?

You’re not not sure.

You pause to think about it. Now everyone in the scene stands around waiting for you to come to a decision. Do they jump? Do they find a bridge? Does one of the heroes have a secret gadget?

How did they even get that gadget?

But you’ve never mentioned the gadget, and now it’s going to sound like it’s appeared out of the blue. To avoid this, you have to go back and add the gadget somewhere else in the story before you forget it exists, and now all the heroes and villains are twiddling their thumbs in front of this chasm, waiting for you to finish the scene.

You need set ups that pay off in big ways in your story, but sometimes the best ones are discovered in draft two instead of draft one. You might know some of your set ups before the story starts, and you probably include these in your first draft plot.

But there will also probably be times that you recognize a plot hole and just need to let them go—until draft two. Pausing to fix them will take up too much of your time, and this will distract your creative process.

You don't want this.

Instead of focusing on plot holes, make a note in a bright color or bold font. “They get over this chasm.” Or, maybe even place a note in brackets [Like this].

You can also add it to your revision list (which we will discuss in a future post) for later. In fact, I encourage this. Make a note and then move on with the story. Finish the scene. You will probably feel better getting that problem down in a place it won't be forgotten—but also so you can forget about it now and get on with your draft.

You will thank yourself for it later.

Plot holes can be filled in future drafts. Even better, progressing your story may even help you come up with better solutions to those problems.

It will also probably save you time, since your plot (and other details) will likely change as your story changes. Wasting your time on a plot hole that might not even exist in the long run won't be worth your time fixing until later in you writing process.

You First Draft Won't Be Perfect

Your first draft will probably come out ugly. It’s imperfect, it’s messy, and chances are it’s full of spelling mistakes and grammar errors and every writing “don’t” that exists.

But that’s okay because that’s exactly what a first draft should look like. Even better, no one has to see your first draft unless you ask them to read it. There's nothing to be embarrassed about if it's not your best draft.

It won't be your best draft, but it is your first step to constructing your future polished draft.

In truth, I have never let anyone see my first drafts. If I can help it, the first draft of Headspace will never see the light of day.

But if you can accept that this is the nature of the first draft, then you will have overcome your first block. Instead of focusing on perfection, you now know that all you have to do is focus on what’s in front of you: the story, the tone, and getting to know your characters.

Once you make it over this hurdle, you will be able to use the tools I give you throughout this series with greater efficiency. And all of these steps will get easier the more you practice applying them to your first draft process.

In the next post in this series, we will take a first look at these tools and get ready to start planning that ugly first draft.

Planning is a great next step—now that you understand what you should care about in your first draft, and what you shouldn't bother with (yet).

Which of the three elements do you struggle to accomplish in your first draft? Why do you think you struggle with this? Let us know in the comments.

If you want to get your book finished faster,

If you want to get your book finished faster,download my book The Write Fast System today!

Get The Write Fast System – $2.99 »

PRACTICE

Today is about some quick planning.

For fifteen minutes, write the big ideas for the beginning, middle, and end of the story idea you've been working on with this series (how to write faster). This will help you develop a small plan for your first draft, and give you a goal to work with until you've finished it.

Completing your first draft will also help you focus on the other two elements needed in your first draft—but that are best discovered while writing your manuscript—tone and characters.

When you're done, don't forget to share your beginning, middle, and end in the comments for feedback. And be sure to comment on someone else's post, too!

J. D. Edwin is a daydreamer and writer of fiction both long and short, usually in soft sci-fi or urban fantasy. Sign up for her newsletter for free articles on the writer life and updates on her novel, find her on Facebook and Twitter (@JDEdwinAuthor), or read one of her many short stories on Short Fiction Break literary magazine.

I get hung up on the details and language. I think of the scenes in this story in vivid vignettes where everything is just so. I have no idea what the characters are saying, or how it moves the story forward, but I can spend a paragraph detailing the cigarette burning down to the butt and falling off the lip of the Tab can.

of course, my biggest challenge is writing the story. I’ve written so many “details in past years, that it hindered me from just telling an Entire story from beginning to end. Thanks JD! After reading your clear process, I’m Finally In My Way!

Writing a synopsis of the story really helped me regain a sense of momentum. I love the idea of a revision list and not getting stalled over plot holes.

One concern I have is that I either over tell/show or don’t go far enough. I’m a decent storyteller out-loud, but when it comes to writing something that is readable for others, that’s a whole new world for me. I’m sure to be a stumbler, but am glad I found a place to at least make a stab at doing it right.

I was doing some of the things you mentioned NOT to do, like worrying about the fine details, trying to use fancy words and styles, and not listening to my character. I will study this lesson, perhaps several times, and see if I can’t improve some of my bad habits when preparing my manuscript.

At the beginning of my story the lead character has come to realize a critical need. He must reexamine his worldview about how to deal with interpersonal relations in both his social and professional spheres. His challenge is to develop a greater empathy with and tolerance for the views and viewpoints of others. He must overcome not only a predisposition to regard his own conclusions as singular and correct, but also to tolerate contrary views and approaches of others. He responds to this challenge by accepting a new job with wider responsibities in a distant location (seeking a “geographic cure”).

The middle of my story deals with how his attempt to change professional. environments and responsibiities brings his shortcomings. into focus. He learns how to deal with differing viewpoints and challenges in order to create an atmosphere of mutual respect and tolerance.

His progress in this. quest. is impeded by a jealous rival who works to thwart his efforts by gaslighting and other means. My character’s task is to discover this rival’s plot, expose his campaign and place him in a position where he can no longer continue to disrupt the local professional environment.

The climax comes when my protagonist accomplishes the necessary goals in his professional sphere, but finds that he has not been able to deal satisfactorily with more intimate personal challenges (the B story).

This denoument forms part of the premise for a sequel.

I am just getting started and reading EVERYTHING !It makes sense but my first question is this: My first book is nonfiction. Are your tips relevant for me or should I be looking at different tips in the Write Practise Thanks!

Hello! You will find tips that apply to nonfiction throughout the site. You could look at our guide to nonfiction types of books here to help you refine the type of book. But if you’re looking for a more guided help, you could check out this previous four session class, How to Write a Nonfiction Book. Good luck as you get your book started!

Great article! True story, my book is about a book that inspired a TV documentary and a movie. I explained what I was writing to the author of the book and she asked “but what is it about?” I have been writing around trying to find a beginning, middle and end. This is where I think the course will help me!

Thank you, J.D. I think this is one of the most encouraging pieces for newbie authors that I’ve read. I’m in the middle of a draft (non-fiction), technically at mid-point toward reaching my goal (c. 30,000 words / 7 chapters), and I’ve been see-sawing back and forth about how to reach the end. You gave me the push, the encouragement, to keep on going doing that *magic* first draft. Thank you for all of us.