Do you want to write a novel but are unsure how to write good fiction? Let's look at the skills you need to do it well.

Writing good fiction takes time and practice. There's no way around it.

However, if you're looking for some specific and valuable writing skills that you should concentrate on improving, this post is for you.

Here, learn the four foundational writing skills that will make you a better fiction writer, with practical tips to better your writing craft.

This article is an excerpt from J. Danforth's new book The Write Fast System. The book teaches writers how to write a fast first draft—in six weeks.

Want to finish your best book faster? Get our new book, The Write Fast System, today (on sale for a limited time)!

Want to finish your best book faster? Get our new book, The Write Fast System, today (on sale for a limited time)!Get The Write Fast System – $2.99 »

Once Upon a Time, I Didn't Know What Was Wrong With My Book

I have personal experience with moving too fast.

A number of years ago (almost ten years now; my how time flies), I finished writing my first novel. I had a vague premise, did no planning, and just dove in and wrote it. I pantsed a 150K word novel, a few pages at a time, over a period of three years. When it was done, I went through the laborious steps of professional editing and self-publishing, and then put it out into the world.

It sold eleven copies to friends and family.

I didn’t do much to promote it and it sank like a stone into the obscurity of the internet. A big part of this was that I didn’t know how to properly market a book back then, but there was another, deeper reason that I didn’t promote this book.

It wasn’t good.

For a first attempt, I suppose it wasn’t terrible. But even back then, reveling in having published a book, I had the nagging doubt in the back of my mind. And at the end of the day, I couldn’t bring myself to ask for support for a book that I didn’t believe was good. How could I ask other people to believe in a book that I didn’t believe in myself?

Back then, I didn’t understand why my book wasn’t good.

To recognize a book lacking in quality was one thing, but to fix it was another. When I tried to pinpoint how to improve it, or even identify what exactly was wrong, I turned up blank. And so, the book never went anywhere.

However, now a decade older and wiser, I know what was wrong.

4 Problems With Books That Aren't Good

My book was plagued by four major problems.

1. Terrible Structure

The book had a terrible structure due to lack of planning. It dragged in some places and covered too much too fast at others. I didn't advance plot in a way that made sense.

I was so occupied with filling a blank page that I never thought about structure. This was a huge problem.

2. Too Many Characters, Not Enough Development

The book had too many characters and not enough development.

While I was truly proud of a few of the characters I created, there were also some who didn’t serve adequate purpose in furthering the story.

Rather than fixing the plot, I dealt with difficult areas by simply sticking another character in it.

3. Too Much Description

Compared to other aspects of writing, I’m good at description. However, I overused it in this book.

I described details down to the minute. Unnecessary details, and I spent far too much time setting up scenes that only got used for a few short moments.

So while my descriptions were written well, they were used poorly and took away from the story rather than enriching it.

4. Needless Dialogue

My characters talked a lot. Correction—my characters talked a lot without saying very much. There were conversations that accomplished nothing or led nowhere.

Do you know what that’s called? It’s called “boring.”

A book with characters who talk in a boring manner is a boring book. Seriously, no one cares what they had for breakfast that day or what was on the radio on their way to work.

Move on with the story already.

How to Write Good Fiction: 4 Foundational Skills

I’m far from the first person to have these aforementioned problems.

In fact, these are some of the most common problems with novels and short stories that “just don’t work.”

When you’re a new writer starting out, figuring out exactly why your book isn’t working can be a confusing and difficult task.

However, when you understand the four foundational skills of writing, you can not only figure out why your story isn’t living up to its potential, but also understand how to change what's holding it back.

The four foundational skills needed to write good fiction are:

1. Strong Structure

I'm sure you’ve heard this word a lot, and this isn’t the post to go into detail about structure. But to put it simply, structure is how the story progresses and how its events are organized. Great fiction has great story structure. Look at any award-winning bestseller or just an all-around good story, and you will see strong structure.

Structure is where you decide what starts the story, what plot points lead the protagonist to make the decisions they do, what occurs that drives the characters, and what ultimately leads up to the climax where everything comes to a head.

To get used to working with structure, it's important to get into the habit of thinking of a book idea in terms of structure, even before starting a first draft.

When a story idea occurs to you, instead of letting it sit as a vague concept (e.g. MC goes on an adventure), try to divide it into the key components that would make up a story—why does MC go on this adventure? What prevents this adventure from going well? What is the goal of the adventure? How does MC change for the better or worse after this adventure? That will help you sketch out the character arc.

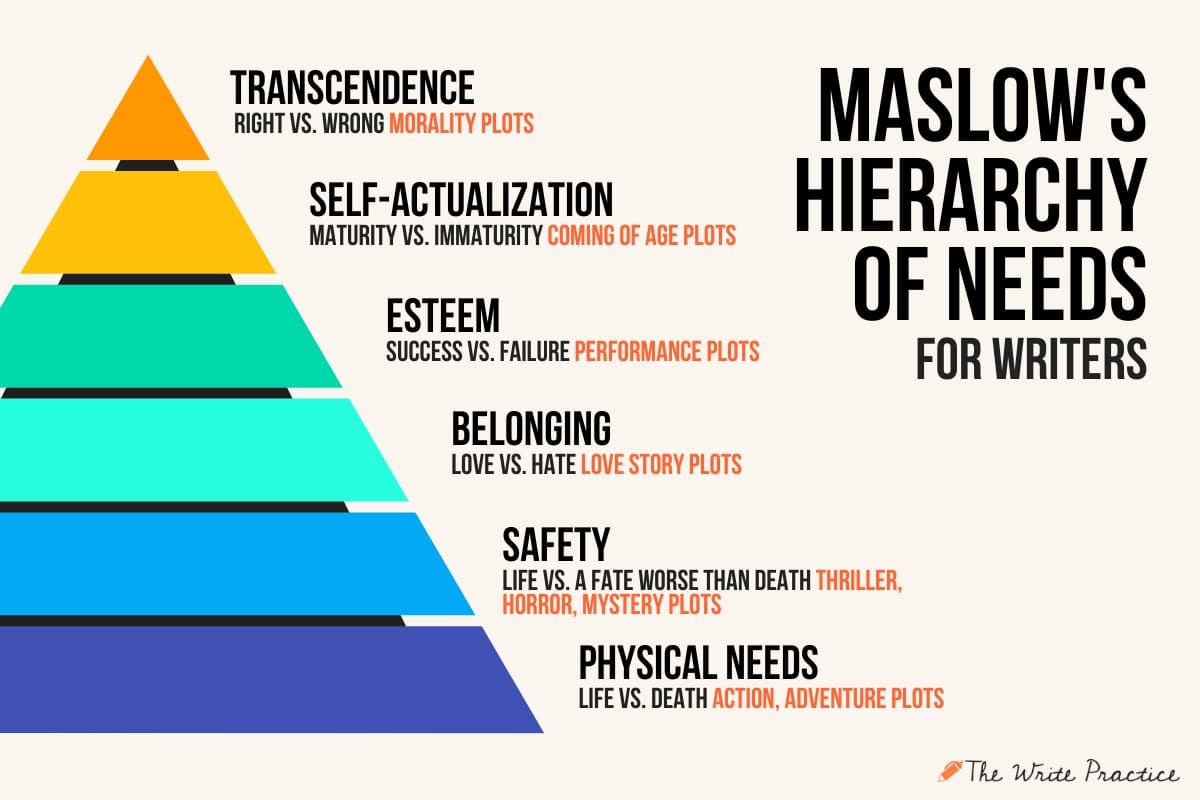

Key components in a story's structure also contain the story's main scenes, which should turn on the driving Value for the story's plot type. In most stories, there are fourteen to twenty main scenes in a plot, and at The Write Practice, there are six main plot types that turn on different Values to consider:

Make this part of your writing process and think about what happens in your story step-by-step. Learning to think of an idea in terms of structure will help you get a better look of your whole book right off the bat.

If your story isn’t working from a structural standpoint, ask yourself:

- Is there an important piece of the structure missing?

- Have I looked at the story and felt satisfied that it makes sense as a whole?

- Do the events of the story proceed logically and give adequate reason for the characters doing what they do?

For further reference on structure, visit the following articles:

2. Develop Characters and Emotions

Your story, at the end of the day, is about someone.

There aren’t a lot of stories out there that aren’t about a character or a cast of characters. But characters are tricky. You need a cast just big enough that every necessary role in the story is filled, but not so many that you fling characters around like a box of spilled beans, so many that readers can't keep character names straight.

In addition to that, your characters need to be distinguishable from each other, having unique reactions and emotions. If your readers can’t tell your characters apart, then it’s not going to make for a very fun read.

A character often comes to mind as an image and a name. But the fact is, a character, main character or otherwise, is so much more than that.

When you imagine a character, try to think beyond the who and focus more on the why of this person—this delves into character motivation.

Why do they do what they do? What in their life has brought them to this point? They're more than just a “happy person” or a “miserable miser.” What makes this character happy or miserable?

When someone wants to know how your day was, you might say “good” or “bad,” and proceed to follow up what's good or bad about it.

A conversation with your character to get to know them is the same. Ask them real question and listen to their answers to write richer characters.

You might be surprised at just how deep and unique they are.

If your story isn’t working from a character standpoint, ask yourself:

- Is every character in the story absolutely necessary? Can some of them be combined?

- Does every action taken by your character move the story forward? If not, they should probably be doing something else, or that part should simply be skipped.

- Does the way each character reacts to major events reflect who they are as a person? Why do they react this way and are the readers aware of the reason?

For further references on writing characters, visit the following posts:

3. Description and Setting

Description provides the visual for your story. Anyone can tell you what something looks like, but using description correctly is actually quite difficult.

It’s important to be aware of what needs to be described and what doesn’t. An object important to the plot may deserve a page of description, but a passerby on the street who isn’t important to the story does not.

The other part of this is that when you go about describing a setting, every component you mention should have some significance to the story. It's not merely about how much description you need to give something important, but also how much you focus on individual parts of it as well.

This principle, quoted frequently in writing courses, is known as Chekhov's Gun, which states that every element in a story must be necessary.

As Chekhov says:

“Remove everything that has no relevance to the story. If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on the wall, in the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off. If it's not going to be fired, it shouldn't be hanging there.”

If your story isn’t working from a description standpoint, ask yourself:

- Have I adequately described all the important objects and settings in the story? Can my readers visualize these things easily?

- Have I overdescribed things that don’t need to be described?

- Are my descriptions interesting? Have I used too many old cliches?

For further reference on description, visit the following articles:

4. Dialogue

There is nothing more active in a story than talking. Dialogue and interaction between characters brings the reader into the situation and gets them involved. But boring, unnecessary dialogue pulls them out just as quickly.

No one wants to read two characters talking about nothing. Dialogue showcases your characters’ personality as well, and bad dialogue means bad characters, no matter how pretty their “golden hair” and “emerald eyes” are.

A useful habit to get into when writing scenes with dialogue is to set a goal for the scene. Where do your characters start talking and where do you want them to end up? How can you pair action with dialogue?

Is the goal of the conversation to discuss a problem and reach a solution? Maybe the goal is to show how much two characters love each other? Is it for the readers to understand a particular aspect of their personality and situation?

Once you understand where you want your characters to end up after the conversation is over, you'll have a much better idea of what needs (and doesn't need) to be said.

If your story isn’t working from a dialogue standpoint, ask yourself:

- Do my characters talk too much? Does every word they say either move the plot forward or show something about the character?

- Do my characters use too many words to get to their point? Sometimes the few words they say, the more impactful their language.

- Do the things my characters say reflect their personality? Is it accurate to their back story and motivation? Consistency is key.

For further reference on description, visit the following posts:

4 Ways to Strengthen Your Foundational Fiction Writing Skills

Now that we’ve identified the skills necessary to make a story work, how does one actually go about getting better at these skills? It may seem overwhelming at first, but in reality, it doesn’t take more than a consistent investment of time.

When I set out to improve my writing skills a few years ago, it felt like a terribly daunting task. Get better at writing? How on Earth do I accomplish that?

In the end, it didn’t end up taking very much time at all. In fact, within three years of starting to work on my writing skills, I had written another book. A better book. A book with a tight structure, well-rounded characters, far improved dialogue, and just the right amount of descriptions.

A book I can be proud of and stand behind, and actually have enough confidence in to promote. It's called Headspace (and it's available now!).

Not only does building foundational skills improve your writing, it helps with revising and self-editing as well. So how do you strengthen your skills?

1. Read books on writing

There are a lot of books about writing. But I am specifically referring, in this case, to books that focus on these four skill areas.

Look for books written by established fiction authors. These are the people who speak from experience and give practical, usable advice.

Some people don't believe writing can be taught. To those people, I ask:

Would you fix a car without first consulting a manual or taking a class?

Or put together a shelf without instructions?

Would you practice law without learning about the laws first?

Books on writing skills offer you the building blocks you need to create your story, and like building a house, you can’t put up the frame without a solid foundation.

For more on how to read productively as a writer, check out this post on what you should read.

2. Read fiction analytically

We all love to read. If we didn’t, we wouldn’t be writers. However, reading to learn and reading for pleasure are two entirely different focuses.

Most of the time, we read fiction to get lost in the story, to become completely immersed and forget that what we’re doing is looking at words on paper. Many of us like to relax with Harry Potter or chew our nails while reading Stephen King.

But to read analytically, we must fight that impulse. It's hard work, but well worth it.

Rather than getting lost, we need to be aware throughout the story and look at it from an objective point of view.

As you read to analyze and learn, try a few different strategies.

6 Ways to Read Analytically (and Learn to Write Better)

- Make note of things you like about the book and try to determine why you like them and how you can replicate the same effect in your own book.

- Make note of things you didn’t like, determine why you didn’t like them, and decide how you can avoid these things in your book.

- Observe the order of events and how they lead up to the whole.

- Take note of descriptions that are vivid and effective. It may even be useful to copy these into a list somewhere for future reference.

- Dissect the book and see how it fulfills each part of the storytelling structure.

3. Write short stories

Short stories are incredibly important. A lot of writers who are used to writing long pieces have a hard time with short stories. Trust me, I used to be one of these people.

But short stories have enormous benefits. Here are three reasons they're fantastic practice for writers:

- They contain all the elements of structure and allow you to see them all at once in the space of only a few pages.

- They are a smaller commitment and less daunting to finish..

- Every word counts in short stories, which is incredibly helpful when you want to practice keeping your writing tight.

Try to make writing short stories a part of your writing life. If nothing else, sharing your short stories is a great (free!) offer to get readers interested in subscribing to your email list.

When you’re not sure what to write, write a short story, or even flash fiction, which is a very short story, as short as just a few words.

Short stories keep the gears turning and your skills fresh. The more short stories you write, the better your skills will be for writing books.

4. Write books

Books. Plural.

The reason I say this is because many writers have this dream of writing a book. There is a tendency to view this book in your head as the end all, be all.

But the reality, unfortunately, is that your first book is not likely to be good, and that’s not your fault.

How many people do you know who do a task perfectly their first time?

The thing is, when you write a subpar book, it’s easy to get discouraged. It can feel like you took a major shot at your dream and it just didn’t pan out. This isn’t true.

The first book is only that—the first book.

Don’t think of it as your one shot, but only your first step. Your first book didn’t turn out well? Shelve it and write another one. Maybe the same one from a different angle, maybe a new one just for fun.

The more books you write, the better you’ll get at writing them. Not only that, you will find that the second book is easier to write, because I promise you, you will have learned a lot from that first book on your shelf.

How to Write Good Fiction: Return to the Basics

Writers who spend time strengthening their foundational skills, especially the four foundational skills mentioned in this post, have unlimited potential.

Often, writers underestimate the need to practice the basics. And because of this, they find themselves stuck in the same weaker areas of their books, wondering how to write good fiction.

Fiction writing doesn't need to be complicated, even if writing itself is a life-long craft.

When you focus on your fiction basics including structure, characters and emotions, description and setting, and dialogue, your stories will only get better.

Never underestimate the value of practicing these foundational fiction writing skills. Over time, you'll see a great difference in your work, and likely, the readers reviewing your stories.

What writing skills do you think teach how to write good fiction? Let us know in the comments.

Want to finish your best book faster? Get our new book, The Write Fast System, today (on sale for a limited time)!

Want to finish your best book faster? Get our new book, The Write Fast System, today (on sale for a limited time)!Get The Write Fast System – $2.99 »

PRACTICE

As you continue to work on the book idea that you're drafting alongside this series, look at the most recent scene you wrote.

Now, go back and review the four foundational fiction writing skills in this post. Which of these skillsets needs the most work?

For fifteen minutes, pull out a specific area in your story's scene and use the practical writing tips in this post to revise it.

When you're done, read it out loud. How does it sound? Better than the original? I hope so!

Don't forget to share your work in the Pro Practice Workshop for feedback, and be sure to leave feedback for three other writers, too!

J. D. Edwin is a daydreamer and writer of fiction both long and short, usually in soft sci-fi or urban fantasy. Sign up for her newsletter for free articles on the writer life and updates on her novel, find her on Facebook and Twitter (@JDEdwinAuthor), or read one of her many short stories on Short Fiction Break literary magazine.

0 Comments