How do you tell a great story? Perhaps the best way to judge a story is by how good the climax is.

If your story isn’t good, the climax will be muddled or boring. A good story, though, will bring together all the tension that has been building since the exposition into one perfect scene with a climactic moment that overwhelms the audience and leaves them in awe.

What is the climax in writing, though? And how do you write a compelling climax?

In this article, I share the definition of the climax in a story. I’ll give examples, talk about where it fits in the dramatic structure, and share writing tips on how to write a good one.

Note: this article contains an excerpt from my new book The Write Structure, which is about the hidden structures behind bestselling and award-winning stories. If you want to learn more about how to write a great story, you can get the book for a limited time low price. Click here to get The Write Structure ($5.99).

Ready to awe your readers? Let’s get started.

Definition of Climax in Writing

The climax in a story is the point, usually near the end of the third act, where the value of the story is tested to its highest degree. As such, it is also the pivotal moment in a story with the greatest amount of drama, action, and movement as the character makes a choice (related to the central conflict) as presented by their dilemma or crisis.

The Climax is a Test of Value

All stories move. They rise and fall. Movement and change is what makes a good story good, and if the story isn’t moving for too long, there’s probably something wrong.

In my article on story arcs, I talked about how stories move. They don’t move through a heightened amount of external conflict or internal conflict, although that’s part of it: more talking, more car chases, more “action.”

Rather, stories move based on the core value that the entire story is about.

For example, a love story’s core value is love, of course, which has its opposite in hatred.

Story Beats for a Love Story Plot

If you put a traditional love story plot on a scale between love and hatred with ignorance in between and mapped out the values, then you might find that the six essential elements of the story (also called the story beats) go like this:

- Exposition: Start In Ignorance. The couple doesn’t know each other, but then they meet and . . .

- Inciting Incident: Loathing. Things go . . . badly. He’s a jerk and she hates him. The value goes down.

- Rising Action:

- Part 1: Attraction. In the midst of their hatred, something changes—he does something kind of noble—and all of that hatred turns into burning attraction.

- Part 2 (midpoint): Problems. Something happens: maybe a rival from her past is introduced, maybe he does something stupid, maybe she gets into danger, or her family turns out to be crazy. Whatever happens, the couple separates, until . . .

- Crisis: Doubt. It begins to look like they’ll never get back together. Was it really meant to be? Maybe they’re better off, maybe the world is better off, if they’re apart.

- Climax: Proof of love. Nope. They were meant to be and one of them is going to prove it, either by driving across the country, or meeting the other in the airport, or interrupting their wedding to the rival, or saving them while sacrificing themselves, or some other dramatic way, all to show their love.

- Denouement: The wedding, the ride off into the sunset, the happy ending, all is well, the end.

Stories that follow this structure include Pride and Prejudice, Twilight, Pearl Harbor, and more.

The Climax Changes with Different Value Types

For our purposes though, take special note of the climax—in this case, the Proof of Love scene. In a thriller, this wouldn’t be a proof of love scene; it would be called a “hero at the mercy of a villain scene.”

Or if it were a mystery novel, it would be “detective explains how the murder happened,” perhaps putting himself/herself into the crosshairs of the villain. Or if it were an adventure story, it would be the big, final, life vs. death battle.

The point is, the type of climax changes based on the value of the story.

In other words, the climax is the moment where the core value of a story is put to the final test, the biggest challenge.

Some people say you need more action in a climax, or more conflict. But you only need action or a huge battle in an action story, and all climaxes are about values in conflict, not conflict for its own sake.

So figure out what value your store is about, then tap into it and bring that value (and its opposite) into the primary conflict.

How the Climax Fits Into the Dramatic Structure

The climax is the second to last element of the dramatic structure. The dramatic structure, as we teach it at The Write Practice, consists of six elements:

-

The climax is the fifth and penultimate element in the dramatic structure, occurring just after the crisis and just before the denouement or resolution.

Since the denouement is usually just one or two scenes long, the climax is usually very close to the end of a story, often the second to last or third to last scene (although sometimes longer denouements are required, leaving the climax further from the end).

Some stories also have the story's chief climax at the end of the second act, not the third. In these cases there may be a smaller climax near the end of the story.

How Long Is the Climax in a Story?

The climax usually is just one scene, and while it doesn’t take up much space in the story, especially compared to the rising action, it is often the longest scene in the book.

Climaxes for Subplots and Scenes

One thing to note is that stories have more than one climax. In fact, every act and even every scene should have its own climax.

Of course, there will be one core climax, the big climactic moment the story turns on and leads up to, but the smaller climaxes in each scene and act continue to create drama and keep the story moving along its value scale.

One of the most important ones, beside the story’s core climax, is the climax in the subplots.

Subplots are shorter plots within the larger plot of the story, and like all plots, they contain mini climaxes.

Where does the subplot climax occur in a story?

The best place for the subplot climax to fit into is the denouement, the final scene or scenes in a story.

That’s why frequently a story with a love story subplot will end with a final kiss between the protagonist and their love interest, bringing to completion the subplot.

It’s important to pay attention to both the core climax and also the climax for your subplot.

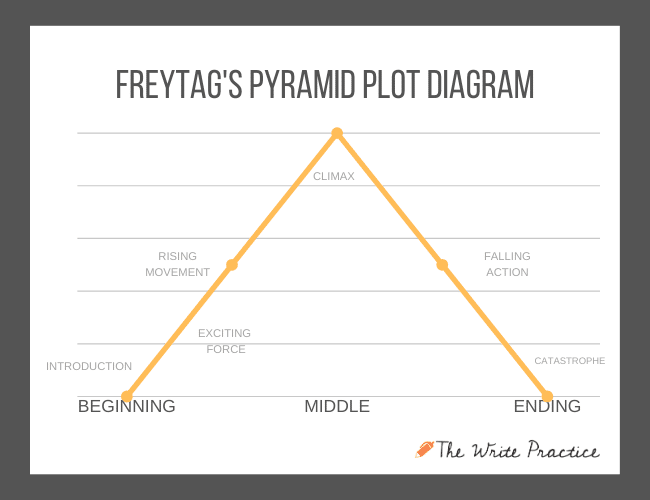

How Freytag’s Pyramid Gets Climax Wrong

Freytag’s Pyramid is one of the most popular and perhaps the most widely taught method of understanding story structure. What most people don’t know, even those that teach Freytag’s Pyramid, is that its originator had a very different understanding of climax than most professional writers do today, even a wrong understanding.

Gustav Freytag was a German novelist popular in the 19th century and the originator of Freytag’s Pyramid, which he examined in his book Freytag’s Technique of the Drama.

Freytag’s climax is different from the understanding we hold today in two main areas: where he puts the climax in writing and what the climax is.

Let’s start with where Freytag considers the climax in literature to be.

Where the Climax is in Freytag’s Pyramid

For Freytag, the climax was in the center of a story, not toward the end. See the plot diagram found in Freytag’s Technique of the Drama below:

The top of the triangle, marked “C,” is the climax, according to Freytag. However, most writers today would put the climax much later in the story. See the comparison of Freytag’s Pyramid to other story structures: Notice how the climax comes much later in the story.While writers today would consider the climax of most stories near the end of the plot, for Freytag, it’s in the center. But that’s not the only difference.

The top of the triangle, marked “C,” is the climax, according to Freytag. However, most writers today would put the climax much later in the story. See the comparison of Freytag’s Pyramid to other story structures: Notice how the climax comes much later in the story.While writers today would consider the climax of most stories near the end of the plot, for Freytag, it’s in the center. But that’s not the only difference.

What the Climax is in Freytag’s Pyramid

The second difference is how Freytag defines the climax.

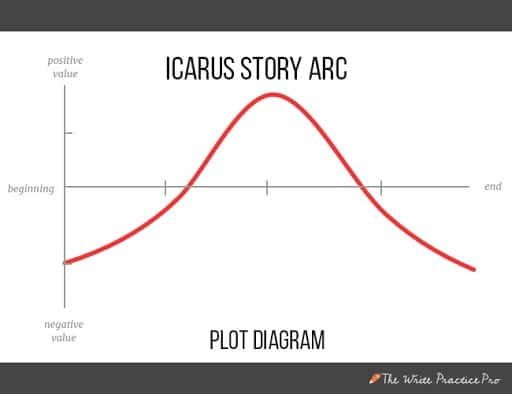

Freytag’s “climax” is much different from how we would think of the climax today using a modern three-act structure. That’s because Freytag was particularly interested in a single story arc, what we call the “Icarus” arc. Here’s a diagram of the Icarus arc:

The Icarus Plot is the classic tragic structure. Examples of climax for the Icarus Plot include Romeo and Juliet, The Old Man and the Sea, Titanic, and so many more. It’s marked by the protagonist’s rising fortunes through the first half of the story, followed by a turning point, then the protagonist’s falling fortunes and an ending at or lower than where they were at the start of the story. Also, notice how closely the Icarus structure mirrors Freytag’s Pyramid.

The Icarus Plot is the classic tragic structure. Examples of climax for the Icarus Plot include Romeo and Juliet, The Old Man and the Sea, Titanic, and so many more. It’s marked by the protagonist’s rising fortunes through the first half of the story, followed by a turning point, then the protagonist’s falling fortunes and an ending at or lower than where they were at the start of the story. Also, notice how closely the Icarus structure mirrors Freytag’s Pyramid. - This isn’t a coincidence, as this was the plot type Freytag was most interested in, the plot he considered the apex of literature. For Freytag, the climax of the story was the peak of the pyramid, the moment of truth when the character’s fortunes reverse. In Romeo and Juliet, this, according to Freytag, is the moment when Romeo says goodbye to Juliet, now his wife, immediately after killing Tybalt and being exiled. Today, no one would call that the climax of the play. Instead, most writers would consider that the midpoint, calling the scene in which the lovers commit suicide the climax scene. Freytag is still the source of much confusion because of this misunderstanding. Many writing teachers share Freytag’s Pyramid without understanding he was working with a very different definition and understanding of climax than we would use today.Thus, be cautious about anyone who teaches Freytag’s Pyramid and places the climax in or near the center of the story, because it’s unlikely they know the origin of Freytag’s ideas and his different understanding of climax.

Climax Examples

To get a better understanding of how climaxes work in stories, let’s look at a few examples of climax from a variety of stories.

Example: The Climax in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone

How does the climax in the first novel in the Harry Potter series work? Spoiler alert!

What is the climax: Harry Potter and Professor Quirrell/Voldemort’s shadow self have a major showdown in the forbidden third-floor corridor, ending with Harry saving the Philosopher’s Stone from Voldemort, hindering his plans to return to power.

In the climax, Harry realizes that Voldemort, whom we previously thought was dead, in fact survived the spell that rebounded on him and has been gathering strength through Quirrell’s help.

When does the climax occur: Third to last scene.

-

What Value is the Climax Testing?

The value the climax is testing is Life vs. death. As an adventure story, Harry Potter moves between the value of life and its negation, death. In the climax it is this value that is tested, as Harry is outmatched by both Professor Quirrell and Voldemort’s shadow and very nearly dies.

There is also a secondary, internal value: education vs. naiveté, as Harry has to apply everything he’s learned at Hogwarts to survive in this one unforgettable climax.

Outcome of the climax: Harry faints, surviving the encounter only because Professor Dumbledore arrives just in time. This proves both Harry’s courage and also that he is not yet a match for Voldemort.

Subplot climax: Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone has a performance subplot with the value scale of accomplishment vs. failure. The scenes that follow the climax, which are part of the denouement, are actually the climaxes of the subplot, ending with the announcement of the House Cup-winning house.

Example: The Climax in Ready Player One

How does the climax in the novel Ready Player One work (the novel version, of course!)? Spoiler alert!

What is the climax: The climax of Ready Player One has two parts.

The first part is the battle between the Gunters and the Sixers over control of the final gate. The battle ends when the Sixers detonate the Cataclyst, wiping out every player in the sector except for Wade Watts, the protagonist, who has an extra life token and is then able to enter the final gate.

The second part of the climax is when Wade goes through Halliday’s final test: finding the correct system to play Tempest on, beating Tempest, and speaking the memorized lines from Monty Python and the Holy Grail.

When does the climax occur: The third and fourth final scenes in the story.

-

What Value is the Climax Testing?

The value the climax is testing is Life vs. death. As an adventure story, Ready Player One lands on the life and death scale, including “digital death” and a sense of real life death, as the Sixers have the ability to do both. (Putting real life death on the table is an important aspect of plots involving alternate worlds, like Ready Player One, The Matrix, and Tron.)

There is also an internal value of right vs. wrong at stake in the climax, wrong being personified in the Sixers but also present, to some degree, in Halliday’s isolation and self-centered obsession with the OASIS. This is something he later regrets and attempts to weed out of his successor.

Outcome of the climax: Wade retrieves Halliday’s egg from the game Adventure, completing the quest and winning control of the OASIS.

Subplot climax: Ready Player One has a love story subplot which reaches its climax in the final scene of the story as Wade and Samantha meet and then kiss for the first time in the real world.

4 Tips to Write a Great Climax

How do you write an amazing and satisfying climax? Here are a few tips:

1. Focus on Your Story’s Values, Not Just More “Conflict” or “Action”

The purpose of a climax in writing is not to have the most conflict or action possible. It’s also not just about creating the biggest reversal of fortunes of your character.

Too often we mistake our character’s fortunes with the arc of the story, and while fortune is involved, it’s not the main criteria of our story arc.

No, the purpose of the climax is to have the most conflict between the values in your story, and the greatest amount of movement in those values. The greatest change in your character growth and fortunes happens because of those values.

So first, find the values of your story. To review, there are six values:

- Life vs. Death

- Life vs. a Fate Worse than Death

- Love vs. Hate

- Accomplishment vs. Failure

- Maturity vs. Naiveté

- Right vs. Wrong

Set those values in the exposition. Begin their movement in the exposition. Raise and lower them through the rising action. And finally, put them to the final test in a climactic scene.

2. Most Stories Have 2–3 Plots, Which Means They Need 2–3 Climaxes

There is always one core plot, one core value, and one core climax. However, most stories have multiple plot lines, almost always two and sometimes three:

- The external plot

- The subplot

- The internal plot

We have talked elsewhere about subplots, but what is an internal and external plot? It all comes down to the values at play in the story.

As we talked about above, there are six values in storytelling. Internal plots focus on the final two value scales:

- Maturity vs. Naiveté

- Right vs. Wrong

External plots, on the other hand, focus on the first four value scales:

- Life vs. Death

- Life vs. a Fate Worse than Death

- Love vs. Hate

- Accomplishment vs. Failure

Most commercially successful stories have an external plot, and many—although not all—also have an internal plot.

When combined with the subplot, that leaves three plot lines, and each of these storylines or plot lines need their own climax.

How do you write three climaxes though?

Often, the external and internal climaxes combine, as we see above in the examples from Ready Player One and Harry Potter, in the form of one major climax or a two-part climax. More on this in the next tip.

Another habit of great storytellers, whether conscious or unconscious, is to put the climax of the subplot in the last scene of the denouement, effectively bringing the story to completion.

By the way, one of the major flaws of the film version of Ready Player One was that they had already resolved the love story subplot, and so there was little tension left in the final scene, leaving the plot to end with a whimper.

3. The Internal Climax Makes Possible the External Climax

Not all stories have an internal plot, but if yours does, often a good way to set up the external climax is through the internal climax.

For example, in Ready Player One, Wade Watts decides to share the prize if he wins Halliday’s contest with his friends. That propels him into the final test and shows that he has what it takes to learn Halliday’s lesson.

In the same way, everything Harry learned at Hogwarts is necessary for the final showdown with Quirrell/Voldemort.

The internal plot, if there is one, sets up the external plot.

4. If Your Climax Isn’t Working, Look to the Crisis

The crisis is the center of your story, the most important of all the six elements. It is also the thing that most pushes your story into the climax.

What that means is that if you’re writing or editing your climax and you feel like it’s not working, go back to the crisis and start there to figure things out.

Why is the crisis so important to the success of the climax?

The crisis or dilemma is always the presentation of a difficult choice, either between two bad things or two good things. It is here that the values in your story begin to be tested in an intense scene.

The crisis isn’t where the protagonist makes that choice. It is where the choice is presented, where there's a sense of urgency because something must be chosen, and even inaction is a choice with consequences.

The climax, on the other hand, is where the protagonist makes the choice, and the urgency and agency of that decision is what drives the consequences, and thus the action, of the climax.

But if you don’t have a crisis, or if the choice your protagonist is facing doesn’t have significantly high enough stakes, then the crisis won’t work and thus the climax won’t work.

The Climax is the Pinnacle of Your Story: Better Do a Good Job With It

How do you tell a good story? Write a great climax.

But a great climax is built upon the foundation of a great exposition, the push of a great inciting incident, the increasing tension of great rising action, and the fulcrum of a powerful crisis.

The climax is the sum of all the parts that have gone before it.

How, then, do you tell a great story? Set up a great climax with all of the previous pieces, then tip the first domino and see how they fall.

What is one of your favorite climaxes from a book or film? Let us know in the comments.

-

Need more plot help? After you practice this plot element in the exercise below, check out my new book The Write Structure which helps writers make their plot better and write books readers love. Low price for a limited time!

Need more plot help? After you practice this plot element in the exercise below, check out my new book The Write Structure which helps writers make their plot better and write books readers love. Low price for a limited time!PRACTICE

Let’s put the concept of the climax in a story to practice using the following creative writing exercise.

Some of the best stories have come from a writer knowing the climax but not being sure how they got there. With that idea, start by writing five sentences to fill in the blanks based on the climax writing prompt below:

- Exposition: ______________________________.

- Inciting Incident: ___________________________.

- Rising Action: _____________________________.

- Crisis: _________________________________.

- Climax: A man and his young daughter disappear on a hiking trip.

- Denouement: _____________________________.

After you write your six-sentence outline, set your timer for fifteen minutes and start writing the climactic scene. Write as quickly as you can.

If you are already a Write Practice Pro member, post your practice in the Practice Workshop for feedback. Be sure to give feedback to a few other writers and encourage each other.

Not a Pro member yet? You can join us as a Write Practice Pro monthly subscriber.

Happy writing!

Joe Bunting is an author and the leader of The Write Practice community. He is also the author of the new book Crowdsourcing Paris, a real life adventure story set in France. It was a #1 New Release on Amazon. Follow him on Instagram (@jhbunting).

Want best-seller coaching? Book Joe here.

Joe it’s absolutely criminal how your siyte is nto bigger. Ive read all the big books, and you are without doubt my absolute favorite teacher. Thank you for this invaluable reosurce.