Why Writers Love Red Herrings: A Brief Guide

Red herrings are staples of the mystery and suspense genres, but they also can pop up in myriad other works and genres. But what is a red herring? Find out…

Red herrings are staples of the mystery and suspense genres, but they also can pop up in myriad other works and genres. But what is a red herring? Find out…

How do you dramatize non fiction? Isn’t real life already wild and crazy enough? And isn’t that why we have fiction in the first place, so that we can be superheroes and E.S.C.A.P.E. our dull routine realities?

Yes, and yes, BUT. The role of literature, in my and many other authors’ humble yet strong opinion, is to reflect social trends and preserve cultural ideals. To inform, inspire, and innovate. The stories we write and read shape our culture and society, our minds and our lives. This is why I insist with the ferocity of a Category 5 hurricane on quality, beauty, and impact.

The reason I write is to open minds—including my own. For me, the most potent way to do that is by mixing up fiction and real life. So let me tell you about The Visionary.

I’m sure you’re familiar with the game Telephone? A group of people get in a circle, and one person comes with a silly phrase like, “The Orange Monkey Eats Green Bananas.” Then, the phrase is whispered from one person to the other around the circle. Each person can only say the phrase once and the listener can’t ask clarifying questions, like, “Did you mean Orange Monkey or Oral Moon Sea?” When the last person has to repeat the phrase, it’s inevitably ridiculous, usually something like, “The Horrible Pokemon Seats Green Cabanas.”

People mishear things all the time, and the game telephone proves it. When something is misheard, the resulting word or phrase is called a mondegreen.

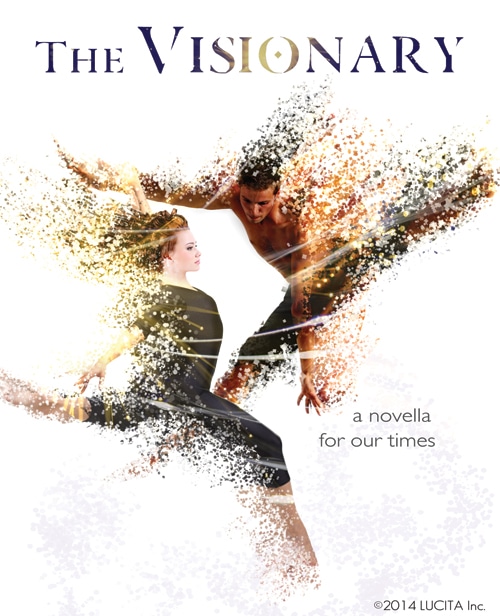

Improve your metaphors and similes with this simple tip.

We humans have been telling stories since we learned to talk. No doubt those tales that sent torrents of adrenaline through our veins also seared the strongest tracks in our memory, and were told and retold through generation after iPad-less generation. Indeed, the definition of myth is “a traditional story, especially one concerning the early history of a people or explaining some natural or social phenomenon, and typically involving supernatural beings or events.”

So where do you draw the line between a myth and a fictional story?

You don’t. You write one into the other.

Nothing adds depth and meaning to a story like symbolism. It acts as webbing between theme and story. Themes alone can sound preachy, and stories alone can sound shallow. Symbolism weaves the two together.

What better way is there to avoid “telling” and instead “show” your story? A symbol conveys complex ideas with few words. Symbolism can also achieve the same results as several sentences of explicit imagery. How’s that on your Show-And-Tell Meter? If a picture is worth a thousand words, a symbol is worth ten-thousand.

The most critical reason I use symbols for me is inspiration. I may have to do upfront research, often spending a few hours collecting a list of symbols for each story, but, like an investment, I get a continual creative flare from it.