You've heard the classic writing rule, “Show. Don't Tell.” Every writing blog ever has talked about it, and for good reason.

Showing, for some reason, is really difficult. Yet, it's also one of the most important writing techniques you need to master if you want your own writing stand out.

Telling is one of the hardest habits to eradicate from your style. I still struggle with it regularly. However, writing that shows is so much more interesting than writing that tells. Most of the time.

In this article, you'll find the definition of “show, don't tell,” see several show don't tell examples, and learn the one simple trick to strengthen your writing style.

What is Show, Don't Tell?

“Show, don't tell” is a popular piece of creative writing advice to write with more sensory details, allowing your reader to hear, see, taste, touch, and smell the same things your fictional characters experience.

This is especially a popular piece of advice given to new writers, who often tell too much in their description (and often include unnecessary backstory or adverbs, which slow the story's pace and take the reader out of the moment).

The descriptive language makes the experience visceral for the reader, which allows them to imagine what a character experiences in real time for that character. Because of this, it's more likely that the reader forgets that they're reading—a goal fiction writers (and all writers) want to achieve.

As Anton Chekhov said, “Don’t tell me the moon is shining; show me the glint of light on broken glass.”

(Note: even though you'll see the above quote frequently, it's a bit of a miss-quote. Here's what Chekhov actually said.)

How do you “show, don't tell”? The good news is that it's pretty easy to show if you just learn this one trick:

Be More Specific

The simplest rule to remember if you're trying to show is just to write specific details. Specificity will fill in the gaps from your telling and bring life to your scenes. Let me give you an example of how being specific will help you show.

Here's a very tell-y example:

They went to New York to see Cats. They both enjoyed it very much. When they tried to go home, their flight was delayed because of the snow so they stayed another night and decided to see the musical again.

That's a fun story. A great trip to the city could be ruined by the weather, but they make the most of it.

It's all pretty vague, though, isn't it? Who are they? What theater did they see Cats at? Why did they enjoy it?

To show rather than tell, you have to interrogate your story. You have to be more specific. Better yet, you'll use strong verbs to show what a character does, feels, and experiences.

Here's that example with some of those questions answered:

Tanya and James flew to New York city in a 747. They got their bags, took a taxi to their hotel, and checked into their rooms. “I can't wait to see the show,” Tanya said. “You're going to love it.”

James shook his head. “I don't get it. It's about cats who sing and dance? Sounds sorta dumb.”

Tanya smiled. “Just trust me.”

Their hotel was just a few blocks from the Foxwoods Theater so they walked. He had never seen buildings so tall or so many people walking on the street. When they got to the theater, Tanya noticed his eyes were a little wider, his mouth a little slacker. The foyer was covered in gold and white marble, with hundreds of people milling around in gowns and beautiful suits. He didn't talk much. Finally, they took their seats, and the lights went down. He took her hand.

….

Let's stop there. Once you get specific your story can get a lot longer. The word count goes up, which isn't always the direction you want it to take.

But overall, at least in this example, the showing is a little better than the blander, tell-y paragraph.

Instead of “they,” we now see Tanya and James. We know a little more about them, that Tanya is a little more cultured, while James is more wary of it. We get a glimpse of the theater.

The second example does a better job at sticking in the reader's mind. The reader gains an emotional attachment to the story in a way the previous example did not.

Interrogate Your Story

There's still more room for specificity, though, which is why you always have to interrogate your story.

What was their flight like? Why is James so awed by New York? What's the nature of their relationship?

Here's another example with some of those questions filled in with specificity:

Tanya and James flew to New York in a 747. Tanya drank club sod and James had ginger ale. “Can I have the whole can?” he said. When they in LaGuardia, James turned to her and said, “Just so you know, that was the first time I've ever flown anywhere.”

“What?” said Tanya. “Why didn't you tell me?”

“I didn't want you to know I hadn't left Oklahoma.”

She took his hand and kissed it and held it to her cheek.

“I'll still love you, even if you are an Okie hillbilly.”

They both smiled and he kissed her.

….

That's definitely more specific, but it's also getting longer. We haven't even gotten to the theater yet.

And what that means is that while “show, don't tell” is often good advice, showing isn't always appropriate. Instead, keep in mind this alternative advice:

Show and Tell: When to Show and When to Tell

Sometimes, showing isn't appropriate for your writing. Sometimes, if you want to write a great story, you have to tell.

How do you know when to show, not tell and when to show and tell? Here's a brief guide:

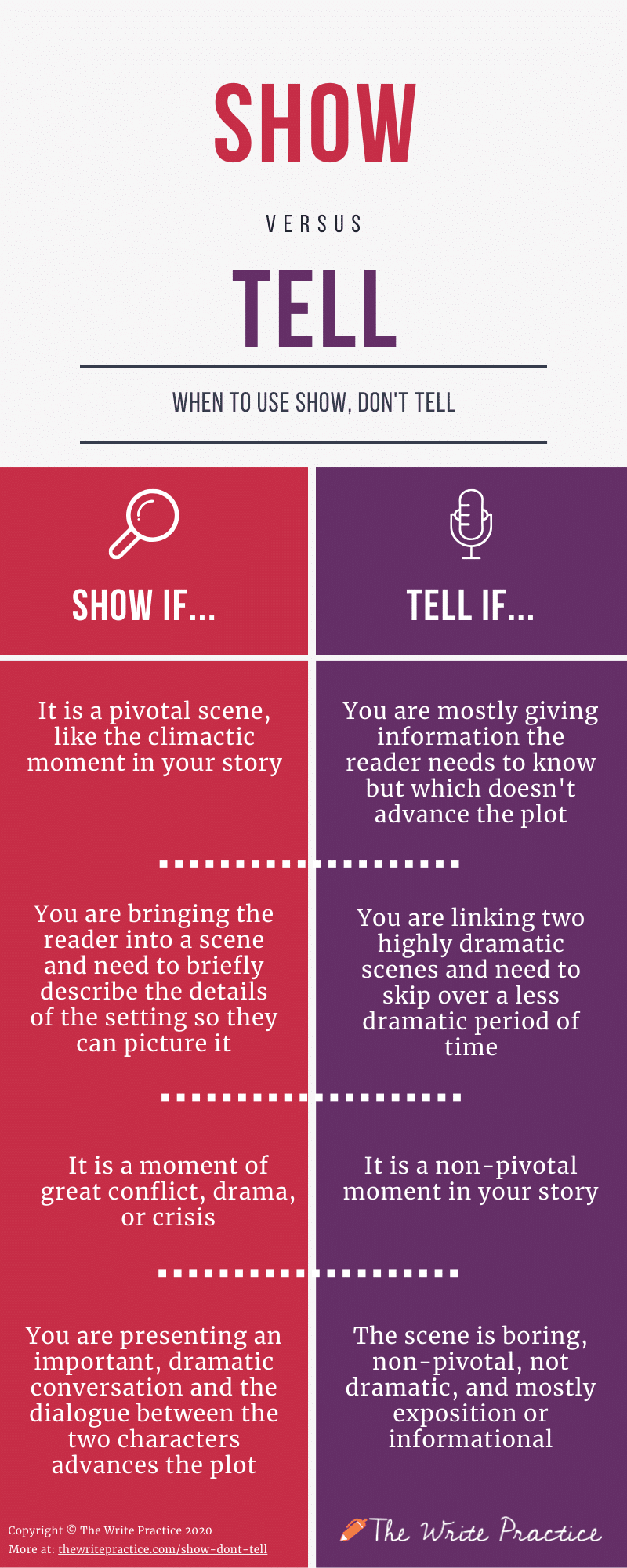

Show if:

- It is a pivotal scene, like the climactic moment in your story.

- You are bringing the reader into a scene and need to briefly describe the vivid details of the setting so they can picture it.

- It is a moment of great conflict, drama, or crisis.

- You are presenting an important, dramatic conversation and the dialogue between the two characters advances the plot.

In other words, show if the scene is exciting, dramatic, story-advancing, character-developing, and altogether interesting. Show if the character has an emotional experience in the scene—or if you want to ground the reader in the character's POV.

Tell if:

- You are mostly giving information the reader needs to know but which doesn't advance the plot.

- It is a non-pivotal moment in your story.

- You are linking two highly dramatic scenes and need to skip over a less dramatic period of time.

In other words, tell if the scene is boring, non-pivotal, not dramatic, and mostly exposition or informational.

I include an infographic that breaks it down visually below. Scroll down for a creative writing exercise to put this concept to use immediately.

How to Find the Write Balance Between Show, Don't Tell

How do you find the write balance between showing vs telling details?

Every story is like an accordion.

You can get infinitely more specific, but the consequence of specificity is length.

While you should want to be more specific, to show more than you tell, you'll need to cut the detail that doesn't add to your story.

If you want to be a better writer, make show and tell a natural part of writing.

To do this, be specific, but don't bore us.

How about you? What do you think is the right balance between showing and telling details? Let me know in the comments.

PRACTICE

Let's put “show, don't tell” to use using the following writing exercise: Rewrite the following prompt by being more specific.

- They went to Los Angeles to see his parents.

Write for fifteen minutes. When you're finished, post your practice in the Pro Practice Workshop here.

And if you post, please give some feedback to a few other writers. I hope this is a community that helps each other improve.

![How to "Show Don't Tell" Correctly [How to Write a Book Coaching]](https://thewritepractice.com/wp-content/cache/flying-press/MA-OyUODfl4-hqdefault.jpg)

Want to Become a Published Author? In 100 Day Book, you’ll finish your book guaranteed.

Want to Become a Published Author? In 100 Day Book, you’ll finish your book guaranteed.

Ricky went with Bill in his old brown Ford sedan affectionatel known as “S–twagon II” to see Bill’s parents, both now retired, whom Bill hadn’t seen in eight years. Bill remarked as they got on interstate 20, “gawd, you can’t even get on the flippin’ highway without takin’ your life in your hands,” narrowly missing sideswiping a truck with a utility bed on it. That was nothing to the gridlock they would encounter nine hours later in the City of the Angels. It was, however, a very entertaining trip in between. They stopped at Carlsbad Caverns long enough to learn that the bat population is now endangered by some sort of strange disease called “white nose”. The one hitch-hiker they saw, whom they declined to stop for, looked like your garden variety wandering serial murderer. We are in search of the REAL America, they joked. The summer heat was in the strength of its youth and their air-conditioner was a model 4-80: four windows cranked all the way down at eighty miles per hour. They took turns driving when one or the other felt fatigued, and listened to the classic rock of their youth on a series of FM radio stations, finding the music of the Grateful Dead especially fitting; but when they found a retrospective on Dan Hicks and the Hot Licks on an L.A. area station, that sent them to their destination in high style. “I think they’ll be glad to see me, but they may not know me so well anymore,” Bill told Ricky as they pulled in the driveway of the small, well-kept cottage. The puzzlement Ricky detected in Mom and Dad donfirmed what Bill had said.

love this – garden variety wandering serial murderer

well done

I agree. Garden variety serial killers are great.

I like “the summer heat was in the strength of its youth” and because these are middle aged men in a car that one would expect a teenager to drive.

Yeah it’s got a nice flow!

I agree with Yvette..Great Flow….

Yes, I agree with Yvette, good flow, and great description that is pertinent and quirky.

Really descriptive and sad

The ending was confusing for me as I didn’t understand why the parents didn’t know who they were. But i liked the imagery in the classic rock and the 4-80 air conditioning system

Masterful clues about the ages of the guys and Bill’s parents using so many unusual yet familiar details. On the second read, I got what was happening with Mom and Dad. Sad but realistic.

Show doesn’t have to be longer than tell, it just has to make us feel it. So, rather than just saying a character was caught in the rain and got soaked, we might describe how his shoes filled up with water so that they squelched at every step.

That’s a good point, Jay. It depends on exactly how specific you want to get with your showing. There IS such a thing as too much specificity. A few chosen details are better than a waterfall of information.

I agree, and if you choose your details wisely, they can speak volumes.

The sun was setting as the plane landed in Los Angeles. The cabin was infused with a golden orange glow. Celebrity hoped was a good omen and squeezed Wayne’s arm to waken him.

Security took forever, Celebrity’s newly coiffured hair was becoming limper than the lettuce left forgotten at the bottom of the crisper. That was the problem, Celebrity thought, I have a name that totally sucks, I am desperately trying to make a good first impression with Wayne’s parents and it really doesn’t matter because my name got there first.

The hair, the new linen suit, strike that, the new crumpled in a heap linen suit, the Jimmy Choo’s that were killing, all of it didn’t matter because her silly, fussy, manic mother once was friends with a woman called Mia with strange named children and she got landed with the stupidest name in the history of stupid names.

And Wayne’s parents had already judged her, and what was the point anyway, I want to go home, she could feel her eyes smart. No way, I am not having mascara run. Where did Wayne go?

Oh I love this man, she smugly smiled as he handed her a bottle of water and a napkin. “Come on Ceely, mom and dad aren’t that bad. They made me. And I love you, honey more than chocolate chilli ice cream, more than anything,” Wayne held Celebrity whilst whispering in her ear.

What a great idea for a story here, Suzie. What a horrible name, Celebrity. I like the words “limper than lettuce left in the crisper” the alliteration draws attention and then you have the contrast of limper and crisper. Great!

thanks, this is the story though, there is no more.

I am composing vignettes of different characters, attached to different characters and scenarios.

I can’t settle to write a “story”

Bags packed. Coach class. Middle seat. If moving back home wasn’t bad enough. “Great. You get the window while I am stuck in the middle.” Joe said as he took his seat in row 16. “How is it that you always luck out?”

James, still staring at the luggage being thrown in the plane. “I wish they’d take their time. I have a bottle of scotch for your dad in mine. It was already aged in an oak-barrel, I can do without a few hours in a cotton T-shirt.”

Joe looks up. Two gigantic Samoans slide sideways down the aisle. Joe hits the back of the chair in front of him where James sat. “You know these guys are going to sit in this row. It always happens.”

The Samoans slowed near row 14 and put their bags above. They slowly walked past 15 and stopped. The one in front glanced at his ticket again and they continued moving.

The plane fills up and Joe is greeted by an older, petite lady who takes up the window seat.

A small victory.

Almost.

A last-minute addition takes up the seat. His gate, through the seeping sweat of his clothes, must have been a half-mile away. He removes a 6” tuna fish sandwich from Subway and lifts up the armrest.

The 5-hour flight to Los Angeles to visit his parents could not get much worse.

The lady turns towards the man who just arrived and notices his sweat-filled University of Maryland shirt.

“You know my daughter went there,” the lady said. “Now her son attends there. I have dozens of stories on that beautiful campus.”

The man commanding the aisle seat leans over and smile. “Well, I think making a friend and sharing stories is a wonderful way to ease this treacherous flight time.”

Hahaha!! This made me laugh. My favourite paragraph is the seeping sweat clothes and tuna fish!

For me, giving the details of what it is like to be at that particular moment and experiencing what is going on is what it is all about. How else could anyone share in what the emotion is and have the imagination develop throughout the scene, if it were not written out to give the complete picture. In my mind, it is a necessity to give the full measure of detail, so that the moment can be shared and explored. Is that not what the beauty of writing is all about.

The essence of show not tell is to get into the skin of your characters. That is, not to describe all the detail of what a tiger looks and smells like when it’s right in front of you, but rather to convey the feeling of facing a tiger. Paradoxically, this can often be more economical than the telling version.

Yes, I agree. The more potent the language, the less of it you need. Ernest Hemingway is one example of an author who could pack more story AND more intimacy into fewer words.

Also, you can start later if what happens at that later point makes it clear what has happened before. That allows more space to insert the important details. For example, you could start right off with, “The flight was delayed because of the snow, so Tanya and James stayed another night and decided to see The Cats again.” The reader already knows from this sentence that the couple traveled and that they’ve already seen the play once. If the good stuff in this story happens in the couple’s conversation after seeing the play a second time, this might be an even better place to start.

Hemingway packed more than just that

Eh I don’t know about that. But maybe I’m misunderstanding you. I think in general talking about emotions is more on the tell side than the show side. I prefer to show emotions through description of setting rather than inner monologue. Am I wrong?

Well Joe in the course I took recently they taught us to show emotion through minor physical appearance changes. Also, through actions and then sometimes you can add in a thought or two as well. I really like your notion, that you can show emotion through setting of scene. I have definitely started using that since joining this group.

That’s a great point, Yvette. I prefer action over physical appearance though.

I don’t understand. If you describe at tiger being in front of someone with enough clarity wouldn’t the reader then be able to feel the emotion that the protagonist is feeling?

Best example I can give is from Vertigo, where Raymond Massey tries to throw Jimmy Stewart out the window. Hitchcock shot this in a bunch of confusing close-ups. A studio exec asked why he couldn’t do it with some long establishing shots to make the details clearer. Hitchcock said, “Because, when somebody is pushing you out of a window, the clear details are the last thing on your mind.”

If you describe the tiger with 25o words of detail, you’re implying the calm viewpoint of a Mr Spock. See the point?

That’s a really good point, Maven. And I love that example. You could do it with 5 words, or you could do it with more if you used stream of consciousness and pinged different details: the black eyes, the three inch teeth, the claws sinking into flesh, the blood, the rumbling of its growls, the sound of ripping clothes and flesh.

Do you have any examples from writing? In film everything is show by definition. The great fear in that movie, and I think you mean Rear Window rather than Vertigo was on James Stewart’s face as the guy threw him out and he tried to hang on. Maybe that’s why people often like movies better than books, but then a lot of people who see a movie after reading a good book are disappointed.

They went to Los Angeles to see his parents in a rental car at Christmas. It was a Ford SUV and since they both drove Toyotas they went for several miles in the cold Virginia winter, before Sarah figured out how to turn the heat on.

“Everything’s on the wrong side in this car, “ she said. The cold was making her fussy.

“Yeah they should give lessons before they put you in one, but this has a lot more room than the Corolla,” said Jason. “It smells like it’s brand new.”

Jason thought the drive would take five days, which would give them four days to stay with his parents in their stucco, three-bedroom home on Kenwood Ave. in the historic distract of Los Angeles.

“Are there really palm trees?” said Sarah.

“Yeah, there aren’t any in our yard but there are some on the street, different kinds. My parents wanted to stick to trees that went with the house which is kind of a fake tudor.”

Sarah looked out the window at empty brown fields and filthy feed lots under gray skies and imagined a sunny city with neat lawns and lots of palm trees. They passed a farm house with a three metal and plastic pink flamingos in the yard.

They stopped in West Virginia to eat, at the Sky Inn, a restaurant recommended by AAA, and were seated in the only vacant booth which was by the door. Each time the door opened a frigid mountain wind blew across their booth, chilling the formica table top. Sarah looked at her fuzzy red gloves and wondered if she could eat with them on her hands. She looked at Jason who seemed unperturbed by the cold. He gave her a wide smile.

“I like traveling,” he said.

“Me too, but it’s cold.”

“Want to change sides?”

“No sit by me and keep me warm.”

They ordered bar-b-que sandwiches with slaw and fries. Jason took the Tabasco Sauce and dripped the orangish liquid on his the shredded pork. Then he added some slaw, put the top of the bun back on, and took a huge bite. He smiled out of the corner of his eyes at Sarah.

“Good,” he mumbled with his mouth full.

Sarah took off her gloves and ate her fries one by one after dipping them in a circle of ketchup. She leaned into Jason as she ate, trying to absorb the warmth of him though his polartec jacket, and thinking about a warm Christmas.

I love the description here! Especially the paragraph about West Virginia. I can really see the frigid mountain wind.

Katie

Thanks Katie

Oh the simple beauty of the blessed details! A clear scene and believable characters. Nicely rendered Marianne 🙂

Thank you very much Yvette Carol

Thanks for the tip about specificity. Yes, I’m guilty of cutting back a lot of times on specifics, because I want to get on with the story!

I went a little bit over the time limit, but here’s what I wound up with.

She had been expecting more traffic. Sara had never been to Los Angeles. Never been outside of the American Southwest. The heat was expected. Welcome. The palm trees, but as the taxi speeds down 101, the knot in her stomach grows tighter.

“They’re going to love you,” Jason says. He kisses her temple, his calm, cool words flowing down her sweat-stained back like a waterfall. Reassuring and refreshing. Never changing. She thinks of the waterfall back home in Arizona. Their secret place.

Breathe.

“I thought there would be more traffic,” she says, struggling to keep the panic out of her voice. ‘I thought we would have more time,’ she says to herself.

Jason takes hold of her hand as the taxi driver exits the freeway. Sara thinks briefly about how her hand is sweaty and he might notice, but then the worry passes as they drive up and around the winding hills. She holds on tighter. On either side of the drive gated homes rise around them. At the top of the hill the driver stops in front of a pale green stucco.

A woman in a kelly green top and not-quite-age-appropriate jean shorts bursts out of the front door. She looks just like the pictures. Animated and full of life.

Jason squeezes Sara’s hand. Her eyes search for his deep brown ones.

“We’re okay,” he tells her. The waterfall pushes her out the car door and carries her onto the grassy lawn, bringing a bright smile to her face.

Dan hadn’t been home in years. He could still hear the door slamming in his mind as he stormed out after one fight too many with his father. The man had expected, demanded, too much from all of his children. Especially his oldest son. And Dan had failed. Again. As he had thrown the hastily packed duffel bag into the passenger seat of his pickup truck the front door had opened and his father had stepped out on the porch.

“Daniel!”

He slammed the door and walked defiantly around his truck..

“Daniel! Do NOT leave! If you leave now … don’t bother to come back! You won’t be welcome!”

Dan threw his body into the driver’s seat and sat for a moment with both hands on the wheel staring straight ahead at nothing. Then he reached, with grim determination into the pocket of his jeans, pulled out his keys, and removed his house key from the ring. He jammed the truck key into the ignition and heard his mother scream, “NO!” just as the engine turned over and caught. He pushed the switch to roll down the passenger window and tossed his house key onto the grassy front lawn. Then he shook his head and drove away.

10 years and neither of them had moved an inch. Such stubborn men they were. His mother had begged him often over the years to make the first move, to apologize and come home. Why had it been so important to him to stand his ground? To refuse to give in? He had been so determined to make the unyielding man suffer and repent. To outlast his father.

He’d outlasted him alright! At what cost? Now the man lay dying in a hospital and his mother had tracked him down to warn him that this might be his last chance. At first he had claimed not to care but Shelly saw right through his bravado. She always did. So she had quietly packed suitcases and called airlines. Now here they were on a crowded airplane from Kenya to Los Angeles. Shelly slept quietly beside him as he stared out at the clouds and wrestled with his past.

I love the sound of the door slamming in your second line, drawing us in. Also, I like the contrast between Shelly’s calm ‘quietly packed suitcases’ and Dan’s chaos. ’10 years and neither of them had moved an inch’ is a great line – but maybe a scene that Dan remembered which proves this would have been more powerful than his thoughts…? Those are my thoughts!

The plane had small windows, June thought. She had thought that the windows in planes would be bigger and brighter, that you’d see the whole city from that view. But no, all you got was a piece of sky.

She sighed and popped her gum. ‘I don’t know if I’m going to like her.’

Matt blinked at his newspaper.

‘She’s obese.’

‘I didn’t say that, I just said she’s not as skinny as you.’ He moved his hand towards his pocket, but then remembered he couldn’t smoke. ‘And she doesn’t like skinny girls.’

As they arrived at his parent’s door, June’s only expectation was to be shunned. She looked at the wreath. A little bluebird sat on a brown twig grinning at them. Matt shook his head. ‘It’s been here for twenty years.’

Matt banged the knocker furiously, on and on and on. She poked him and rolled her eyes. He just carried on.

Finally a huge man with a grizzly bear beard flung the door open, nearly knocking himself out.

‘Mattie’s home!’ He yelled, his voice real deep, but with a bounce in it too.

June smiled as he closed in on Matt and they man-hugged. It started out as a good hug, but then it just became embarrassing so she pushed them apart and stuck her hand out to greet him. ‘June’s the name.’

Grizzly bear started laughing, and then pushed her close to his chest. ‘Oh we don’t do handshakes,’ he said.

June thought he held on for a little too long, and when the footsteps clipped down the hallway, he threw her off him like a bad rash. There, coming down the hall, as prim as a stick but wide as a ball, was the Mrs.

‘What a nice surprise,’ she said, her frozen eyes fixed on her husband. ‘You’re early.’ She stuck out a taut hand for June to touch.

Ah, June thought.

Hmmm… reading it through, not sure if I did the ‘show vs tell’ thing here… Comments? Suggestions?

Hey Zo-so I thought there were some really nice little jewels in there, like the man-hugging, the deep voice with the bounce in it, and ‘the Mrs.’ Also, the ‘stuck out her hand’ line was tight, it painted a picture without a lot of words. Suggestions? As Joe said elsewhere, take out the ‘remembered’ part because that’s telling, and just perhaps show his eyes flick up and take in the ‘no smoking’ sign….

Thanks Yvette!

I noticed June’s almost hostile attitude, and how even though she didn’t think the mother would like her, they had similar personalities.

I think this is a strong piece, I really like how the ending had such strong imagery and made the reader think about the situation. I also like how you wrote ‘we don’t do handshakes’ but then the mother holds her hand out for June to shake– it’s a very strong point where you used more showing and less telling.

Becky sat in the passenger and fidgeted with her hair. The desert air dried her sinuses, but Carl had insisted on keeping the top down. And as if this trip couldn’t grate on the sense any more, the seams in the concrete kept her from enjoying her Creed album.

She glanced at her first real boyfriend, his hands resting on the wheel. Family was important to him, which was why she agreed to come along, but that didn’t mean she had to share the sentiment. Some people just can’t cut the cord, Becky thought.

Carl reached over and gave her neck a quick massaging rub. “Don’t worry, hon. I’m sure they’ll love you as much as they do me.”

She wanted to snort, but smiled instead. Yes, she wanted to get to know Glenda and Martin eventually, but to make a special trip just to see them seemed a bit over the top.

“How do you think they’ll react to, well, you know?” she asked.

He took his eyes off the road for a second and looked at her before staring back down the interstate. “We don’t need to go into that yet,” he said. “After all, you were trying to get enough money to finish school. Just go with that for now.”

“I don’t feel comfortable lying to them,” she said as she turned to watch the passing scrub brush.

“It’s not lying,” Carl sighed. “You just don’t have to go with all that brutal honesty you always have. Not at first.”

“You want me to be someone I’m not.”

“No,” Carl admonished. “I want them to give you a chance so they can love the real you. The way I do.”

They drove in silence for a long time. Becky began to feel a queasiness in her stomach that had nothing to do with winding their way through the downtown streets once they turned off of I-5. They finally pulled into the parking lot of an In-n-Out Burger, and Becky saw a stern looking woman standing beside a BMW. Surely, she thought, that was his mom. However, it was when his dad got out that her heart skipped a beat.

“Shauna?” he gaped, his jaw slamming the asphalt.

She knew not all of her clients lived in Las Vegas, and that most of them used fake names, but this was an unwelcome surprise.

Great story. Kicker of an ending.

I loved the story that you wrote! I am also a great writer too

Apparently great writers use “also” and “too” in the same unpunctuated sentence.

The sign of a great writer is not being afraid to break with convention and rules in a meaningful way to produce good writing; that said I don’t see this as that.

Speaking of convention, “that said” and its variants are woefully overused these days. I guess it sounds more important than “but.”

Crikey! (as they say down in these parts) I wasn’t ready for that ending. I think my stomach dropped, it was the ‘her heart skipped a beat’ bit that twisted the whole scene somehow in a sickening direction… Phew! Nice job RD!

That is really good surprising ending I really like it

Good job

I must say the ending is one of the best Lil tricks I have noticed in an author who isn’t Mr or Mrs famous author. Great job !

twist ending – I thought at first she was a surrogate, but then…

I didnt understand it at first, but the twist at the end clarified. Great story.

I really like how you didn’t let the reader know exactly what was happening until the very end, even then the reader still had to draw the conclusion for themselves (somewhat). It also had very strong diction and great imagery.

The ending definitely caught me by surprise because the whole time I was reading I thought she was pregnant

I didn’t get the story at first but having a discussion after helped me understand the story. It did a good job in showing me when what was happening instead of telling me. The imagery was strong.

I loved the ending–great twist! I read along thinking that she was a liar, and maybe a pregnant one at that. This is the sort of story that demands an ending–so–great job, really great job.

Thanks for sharing this Joe. As a writer without formal training, I haven’t quite developed this habit yet. But this is a great way to help remember what I need to do.

As the plane took off, he couldn’t stop thinking about the moment when he received the phone call.

He knew the call was inevitable. Noah acknowledged the reality of this truth, but he had still pushed it away as if ignoring it would somehow hold it off.

His wife was the one who answered the phone, and when she handed the receiver over to him, he knew that moment had come.

“Dad?”

“Hi Noah. I have some bad news about your mother. She has cancer. The doctors give her 3 months.”

His entire childhood played like a silent movie through his head. Every cherished moment with this women had been the most absolute thing he had known in his life. Every missed opportunity to give back to the one who had given him everything. Every time he had hugged her. Every time he had yelled at her in anger.

It all fell on him at once. A heaviness that pressed his soul down to the floor even though his body remained standing.

After what seemed like an eternity to him, but was really on a short pause over the phone, he came to with a question from his father.

“Son, are you there?”

“Yeah, sorry. We will get there as soon as we can.”

He paid too much for two tickets on the earliest flight he could find. He filled his suitcase with items he wouldn’t need, forgetting basics like shampoo and shaving cream. Thought they were together, he couldn’t feel more alone.

They were headed to Los Angeles to see his parents.

Hey Jeremy,

This is a powerful story. I like the emotional weight it has. You do have a lot of telling here, although I don’t particularly blame you for not getting it. The post wouldn’t have helped you with all of this telling. Let me break it down:

“He couldn’t stop thinking about the moment when he received the phone call. He knew the call was inevitable. Noah acknowledged the reality of this truth, but he had still pushed it away as if ignoring it would somehow hold it off.” This is inner monologue, which, in my opinion, is like the definition of telling (you can’t really show inner monologue).

“His entire childhood played like a silent movie through his head. Every cherished moment with this woman had been the most absolute thing he had known in his life. Every missed opportunity to give back to the one who had given him everything. Every time he had hugged her. Every time he had yelled at her in anger.” This is kind of a mix between backstory and inner monologue and a few pieces of action. Instead, you could make it all action by saying, “He remembered when he was sixteen and he broke his leg playing football and she came to the hospital room and hugged him tight and he felt like a child again, safe in her arms….” Of course, there’s still some inner monologue there (any time you say “felt” and “remembered” but it’s still more specific.

“He filled his suitcase with items he wouldn’t need, forgetting basics like shampoo and shaving cream.” It’s hard to be too specific in 15 minutes, but for next time, what items did he put in? And rather than telling us he forgot basics, just show us he forgot his toothbrush and shampoo and shaving cream. To really show, you have to trust the reader is going to get it.

Does all that make sense? Questions? Disagreements?

You are right and it does help.

This is a difficult habit to train myself out of.

Thank you so much for posting this. I’m in the middle of my second rewrite and I’ve been struggling with this daily. Not only did I join your mailing list but I’m going to bookmark this page so I can come back and reread it when I have trouble.

Thanks also to Jeremy who was the first brave soul to post his practice paragraph.

Good job, I read your story before I started writing my own and then almost named one of the characters Jeremy!

Anyway, I also struggle with showing versus telling. One thing that I’ve been doing is trying to imagine it in my head and then pull out details from the scene and describe them.

I’m also reading authors whose prose I admire and and copying paragraphs down which have devices that I like.

Good luck!

who are your favorite authors?

Sorry, I thought it would tell me when someone replied.

My favourite authors are a little unusual in that they come from a wide varied genres but I really like Brent Weeks, Diana Gabaldon, Yoshikawa Eiji and Orson Scott Card.

But my absolute favourite is Frank Herbert. Half of his books are lessons in everything from politics to human nature but the man could and make up profound sayings that will make you think he must be copying from Solomon or something.

If you have time read Dune. I’ll never forget it. And stay away from David Lynch’s abomination of a movie.

You are so right that detail makes things longer. I have trouble figuring out how much detail to put in. Anyway, here’s my 15 min. writing.

They took the long way. Sam didn’t even bother calculating how many days it was going to take because he didn’t want to know. The longer the better; he wasn’t looking forward to what he had to do once they got to L.A.

Perry pressed him on that point, but apparently he didn’t care that much either. He relented as soon as they pulled the Rabbit out onto the highway and opened the first bag of Cheetos. Sam was prepared for the piles of crap that would accumulate on the road. Perry’s fingers were already covered in greasy orange dust. Sam tried not to think about it smearing on his bare skin, leaving trails of neon on his abdomen.

L.A. – he hadn’t been back in years. Perry had never been. Sam’s parents had quizzed him on what “his roommate” liked to eat for breakfast, what kind of drinks he liked. He didn’t think he could tell them Perry’s favorite drink was a lime jello shot slurped out of Sam’s bellybutton.

He’d tried to tell them so many times, but at the last minute he’d always balked. He didn’t really know why. He just couldn’t get the words out of his mouth. He could see the stunned look on his parents’ faces, the drag of disappointment in their eyes. Their only son wasn’t going to give them a new generation of Lowensteins.

“Is the Grand Canyon on the way?” Perry asked, struggling with the map and chewing cinnamon gum. Sam hated that cinnamon gum. He wasn’t kissing Perry until he got rid of it.

“If you want it to be,” he replied.

“Yeah. I want to see it. I want to go to the Four Corners and put my hands and feet in four states at once.”

Sam snickered. “Sounds good. Figure out the route. Feel feel to take the scenic one.”

“Sam, it’s going to be fine. Your parents live in L.A., for god’s sake, they’re not exactly Bible Belt fanatics.”

“You don’t know them. They’re lining up nice Jewish girls for me to meet even as we speak. And it’s Orange County. Not exactly the same as L.A.”

Perry ruffled his hair, a hand lingering on his bare neck. It felt good. He was suddenly glad they were taking the long route. More time alone with Perry. Perry’s schedule had been crazy the last few months. “I’m planning my charm offensive right now. They won’t know what hit them. They’ll be calling adoption agencies for us before the week is out.” Perry tried to reassure him.

If anyone could charm his parents, it was Perry, Sam had to give him that.

Sam dragged his eyes from the road to look at Perry. “I hope so. You certainly charmed me when we first met.”

Oh man. Reading this over, I see so much “tell.” I might rewrite it.

There’s a good amount of showing here, and enough of the important details (the slurpee, the gum, the cheetos etc.) with each of them having a reason for being there. I think it’s very clear and fairly subtle.

Thanks for the feedback. It’s good to know! I do see some sentences that I think I can cut out.

You are so right that detail makes things longer. I have trouble figuring out how much detail to put in. Anyway, here’s my 15 min. writing.

They took the long way. Sam didn’t even bother calculating how many days it was going to take because he didn’t want to know. The longer the better; he wasn’t looking forward to what he had to do once they got to L.A.

Perry pressed him on that point, but apparently he didn’t care that much either. He relented as soon as they pulled the Rabbit out onto the highway and opened the first bag of Cheetos. Sam was prepared for the piles of crap that would accumulate on the road. Perry’s fingers were already covered in greasy orange dust. Sam tried not to think about it smearing on his bare skin, leaving trails of neon on his abdomen.

L.A. – he hadn’t been back in years. Perry had never been. Sam’s parents had quizzed him on what “his roommate” liked to eat for breakfast, what kind of drinks he liked. He didn’t think he could tell them Perry’s favorite drink was a lime jello shot slurped out of Sam’s bellybutton.

He’d tried to tell them so many times, but at the last minute he’d always balked. He didn’t really know why. He just couldn’t get the words out of his mouth. He could see the stunned look on his parents’ faces, the drag of disappointment in their eyes. Their only son wasn’t going to give them a new generation of Lowensteins.

“Is the Grand Canyon on the way?” Perry asked, struggling with the map and chewing cinnamon gum. Sam hated that cinnamon gum. He wasn’t kissing Perry until he got rid of it.

“If you want it to be,” he replied.

“Yeah. I want to see it. I want to go to the Four Corners and put my hands and feet in four states at once.”

Sam snickered. “Sounds good. Figure out the route. Feel feel to take the scenic one.”

“Sam, it’s going to be fine. Your parents live in L.A., for god’s sake, they’re not exactly Bible Belt fanatics.”

“You don’t know them. They’re lining up nice Jewish girls for me to meet even as we speak. And it’s Orange County. Not exactly the same as L.A.”

Perry ruffled his hair, a hand lingering on his bare neck. It felt good. He was suddenly glad they were taking the long route. More time alone with Perry. Perry’s schedule had been crazy the last few months. “I’m planning my charm offensive right now. They won’t know what hit them. They’ll be calling adoption agencies for us before the week is out.” Perry tried to reassure him.

If anyone could charm his parents, it was Perry, Sam had to give him that.

Sam dragged his eyes from the road to look at Perry. “I hope so. You certainly charmed me when we first met.”

“Why are we going to visit them again?” Mary asked for the third time in an hour.

“You know why.” He said. “And please stop pestering me about it. You know I don’t like it when you harass me about my parents.”

“Bobby, they aren’t even really your parents, for God’s sake! Why do you have to bow and cater to their every whim?”

“I would think that you would know by now exactly why.” He said. “And after everything they did for you, despite your situation I would think that you would be a little more grateful.”

Bobby pulled the car into a gas station and got out slamming the door harder than necessary.

Maybe I pushed it too far, she thought. But I’m tired of coming all the way out here every time his “mother” has an episode.

Bobby got back in the car, not looking any happier than when he left.

“Look Bobby, I’m sorry that I brought it up more than once but I’m the one that suffers when we go there. They may have accepted me as you say but that doesn’t mean that they don’t make their opinions known.”

“Fair enough.” He said and started the engine. “But don’t forget it’s only been two months since we checked mom out of the institution.”

“Please stop calling her mom!” She shouted before she could stop herself.

“Why should I?” He shouted back.

“Because, you were eighteen when you moved in!” She said. “It’s weird!”

Bobby looked down deep in thought and then nodded to himself seeming to make a decision. “I don’t care. It’s call them my parents or never know what it’s like to have them. What would you prefer?”

The bitterness in his voice was obvious and Mary knew that the answer she gave would determine what would happen between them forever.

“How’s your dad taking it?” She said.

The crease in his brow vanished and his shoulders relaxed. “Like he usually does, with a carton of wine.”

Joe this is a great prompt, thank you for it and how you encourage me. Nervously I am letting go of my little story based on this prompt.

They went to Los Angelos to meet his parents

The light faded as the Chevy moved through the desert. Chewing on her nails, she watched Jesse from the corner of her eye. Several times she had opened her mouth to speak but had closed it without making a sound – words where far away.

‘I love you’ Jesse said, glancing at her for a moment, before returning his eyes to the road.

She turned to face him.

‘I love you’ he said again.

Tears fell down her face. He stopped the Chevy, gravel crunched under his feet as he walked round to open her door. Lifting her out of the truck he cradled her in his arms.

‘She’s gone, sweetheart,’ he murmured as he rocked her, ‘Mama’s gone’.

‘Where Daddy? Where has she gone?’ her little voice whispered against his cheek.

‘Heaven baby, Mama is in heaven’ Jack answered.

‘I miss her Daddy.’

‘So do I.’ he said

‘Can Mama see stars in heaven, Daddy?’ she asked looking up to the sky

‘I don’t know baby.’ He said, as he looked up into the vast blackness that was twinkling with light

‘I think Mama can see the stars Daddy.’

‘I hope she can, baby. Mama loved stars and she knew their names.’ Jesse said .

‘Will you teach me the names of the stars Daddy?’

‘I will.’ Setting her down on the ground, he pointed out the North Star and said that was the one they were following to the ocean.

‘Why are we going to the Ocean Daddy?’

‘I’m taking you home baby, to where I grew up with Gramps and Granna on Leo Carrillo State Beach.’

Jim had never been to the west coast before. The flight was interminable and the coach seats were claustrophobic. He hadn’t been sure wat he could bring through security, so he hadn’t packed any food, and then he balked at the prices in the airport. Now he was left picking at some rubbery chicken in a gelatinous gravy. If it had been in a foil tray with a little cherry pie baked right into the corner at least he could be nostalgic instead of repulsed.

He twisted the platinum band on his left hand. It was still a foreign body. He would catch a glimpse of in from the corner of his eye, distracting him from everything else.

The Sierra Nevada hung below his window. There was nothing on the east coast to compare to this unbroken, vast, and jagged depth. They reminded him of the drawings of the deep sea trenches in his childhood atlas. Those pages were terrifying, the unknown lurking in those gashes on the page.

He felt a warm hand cover his tense knuckles on the armrest, over the ring cutting into his skin.

“They’re gonna love you, you know.”

“But we didn’t invite them to the wedding.”

“We pretty much didn’t invite anyone to the wedding. It would have been too much for them to fly to New York. We’ll have a party or something when we get there.”

“You know why I’m…”

“I know. It’s going to be fine, hon. I promise.” Earl took his hand in both of his own and squeezed. Jim could feel the rings scrape lightly against each other and hoped Earl was right.

Seamus and Jodi sat in silence in the hybrid, listening to the music throbbing mutedly through the small but technically marvelous speakers Seamus had had installed before the trip. He had wanted to make sure the speakers were perfect for their twenty hour drive down Highway 101 to Los Angeles. It was his car – his first new car ever.

He had purchased a brand new hybrid in order to make sure he was being as environmentally friendly as possible. He wanted to make sure that his greenhouse emissions would be minimal. He liked the sun and warm weather, but didn’t want to be responsible for burning the planet up. However, the stereo had not been up to his level of quality. But that was an easy enough fix. It seemed that with enough money, everything was easy to fix.

Jodi stared out of the passenger window, watching the ocean fly by in one postcard moment after another. This was the first time she had ever been down highway 101, and it was nothing less than amazing. She thought back to what she knew about it. Not much, she realized with distaste. It was kind of her ‘thing’ to know a little something about everything. She thought it had been built during the depression, a government program to keep people working.

“So, what do you know about this road?” she asked, cocking her head to emphasize the question.

“What do you mean?”

“Well, it’s beautiful, right? But, like, why was it built? Why here, when… you know, all that stuff.”

“Oh. Hmm, let me think.” Seamus bit his lower lip, his brow furrowed in thought. On the radio, R.E.M.’s ‘It’s the end of the world as we know it (And I feel fine)’ came on. All thought processes stopped and, both Jodi and Seamus smiling broadly, they started to sing the words. “That’s great it starts with an earth-quake, birds and snakes and aeroplanes, Lenny Bruce is not okay…”

“Daddy, look!” Mia said enthusiastically, making Adrian wake up from his sleep, taking his attention outside the airplane window where he could see the clouds being painted in beautiful colors, as if taken out of a movie, “they look like cotton candy! Can we go to the fair with grandpa and grandma?” she said with wide, attentive eyes. “Of course sweetie, but we have to get off the airplane first,” Adrian giggled while trying to fix his daughters’ hair which seemed like it had not been brushed in days.

Once they arrived at the Los Angeles airport, he took her hand and did not let her go at all. The last time he had been here was almost eight years ago, and it was as chaotic as always. People seemed to swim along a current; you had no time to look back, unless you wanted to be trapped in between. After Mia was born, Adrian had moved with his wife to San Diego, seeking a new start together. He suddenly began remembering the many adventures he had with the love of his life in what seemed now a different world. He realized her face was beginning to look blurry in his memories, and pain struck his chest. He could not forget her, not now. Not ever.

“Daddy, how does grandma look? Does she have curly hair like us?” Mia interrupted his thoughts, and it seemed like all she did lately was ask questions. At least this kept him distracted. “Yes, but her hair is lighter and longer than ours.” She looked at him, concerned, and said, “Is she mean?” Adrian giggled, looked at her closely, and replied, “She is the sweetest woman in this word, and she will be very happy to finally hold you in her arms.”

When they arrived at the hospital, Adrian began to feel a warmth that began in his chest and spread to his head. He wiped his forehead and noticed how cooler it felt inside the building. “Uh, excuse me, ma’am. I’m here to visit my mother, Katherine Franco,” he managed to tell the receptionist. He licked his lips and noticed how dry they were. “Please, sit down and I will call your name in a minute,” she said with a comforting smile.

They sat, waiting for what seemed like an eternity. His leg was shaking so hard it seemed like it was about to detach from his body. He looked at Mia, playing with the toys that were laying on the floor, as if resting from the long games they had been part of today. Looking at her, he could not help but notice how much she looked like her mother. Her blushed, chubby cheeks and her long, curly eyelashes reminded him of the woman that stole his heart. He shook off that thought; it wasn’t the place or the moment. Mia needed him, and he did not have time to be weak. They needed each other. His mother needed both of them.

Once the nurse showed them the way to the room, he paused before opening the door, glancing at the flowers he had bought on his way to the hospital and admiring their beauty. He wished he could have bought a card too, but he did not find one that said enough words to describe how he felt at this moment. Mia wrapped her arms around his hips. He put his arm around her, and after a moment, he took her by the hand. “I’m ready,” he said while he opened the door and stepped inside.

Wasn’t very descriptive, and some parts didn’t really make sense but it definitely has a lot of imagery

I didn’t understand what was happening with the grandmother in the story and was upset about the mother dying but the description of the little girl was perfect and of outside the plane window.

I think you are trying to say something to the effect: drop the authorial authority and replace it with interiority and mush. This s d t rule seems to end in something samey, tedious and, worst, celebratory-of-the-human-condition (American version). No wonder there are so many near-identical novels turning up.

Not really, although I’m not sure what interiority and mush is. Or what authorial authority is, to be honest. Perhaps you could clarify.

Funny though no one in the Shiro Clan ever got arrested. Then, again, his

stay in this Yakuza clan was actually quite different from his stay

in others. The Shiro Clan’s fierce front was just a facade since

underneath all of that the people recruited actually cared about the

strangers brought in.

When Rune was recruited into the Shiro Clan he expected nothing much less

from the other clans. More drug dealing and hearing sex sounds.

However, he was wrong. He saw a lot men and women but nothing illegal

going on. What he saw was karate training, kendo training, and muay

thai training.

When he explored deeper into the headquarters with his guards by his side

which actually made him look like a Yakuza boss, he was shocked to

see rehabilitation centers and women counseling others and telling

them about their past.

In reality, the Shiro Clan was nothing like what the other clans

described it. The most feared, powerful, and dreaded clan that

brought billions into the economy (Master Shiro actually gives a

portion of the money to the community that Mei lives in, mind you)

was actually an organization aimed at tearing down the Yakuza once

and for all.

I have just written my first novel and found your blog yesterday as some of my proofreaders advised me to ” show, not tell”. I have done my best in these paragraphs but I am still not sure if it is ok, and where I need to improve. My book is a fantasy book. Is this rule still applicable for fantasy novels? Here’s my attempt at “show not tell”.

The flight to LA, where his parents lived, was due to leave JFK at 10:15, and it was now 10:00 am.

“Run” she said, her red high heels clicking on the tiled floor and he rushed to keep up, dragging his brown suitcase and her red Samsnite one behind him towards the check – in desk, where a bolond- haired lady in an American Airlines unifrm was waiting to checjk their passports, check their bags in and give them their boarding passes.

“Where are you flying to today sir?” she asked him

“LA” he replied , smiling at her as she checked their passports and put their suticases on the conveyor belt.She handed him their boarding pases and they were done.

“Have a great trip” she said.

“Thanks” they replied, and turned to leave the check – in area .

After they had checked in, they went through Security and finally reached the departure lounge.

James wiped his brow and sat doen heavily . Tanya sat down next to him and pulled a People magazine out of the bag she was using as handluggage. She browsed through the pages until their flight was called.

“American Airlines flight 278 to Los Angeles now boarding” said the disembodied voice over the loudspeaker.

Tanya closed the magazine and stood up, smoothing her cream linen skirt down . She had made a good choic teaming it with a light peach chiffin blouse she thought.

“LA here we come!” said James as he walked slightly in front of her, his beige shorts and blue and red short sleeved shirt the most comfortable thing he could find for the flight. He had white Nike trainers on his feet.

As they settled into their seats on the plane , he signalled to the air hostess, who bought them Cokes.

“Ah, this is the life” he said , and the ice in his cup rattled as he lifted it to take a drink. Tanya put the seat back and said “I’m just going to have a nap”. She closed her eyes –

Before long, the plane landed in LAX, and whem it came to a complete stop, the heat hit them . It was so much warmer here than in New York.

Tania loved the sun, and pulled her sunglasses out of her cream Chanel tote bag and put them on . They were large round Jacki O’s.

They descended the steps to the tarmac and walked across it with the other passengers toward the Terminal building where they were soon lost in the crowd of excited travellers.

Fifteen minutes later they emerged into the Arrivals area, where James’ parents, Tim, a grey – haired man and Jill, a lady with dyed blonde hair were waiting.

“Welcome to LA!” they said , and hugged them both, before James and his dad took the suitcases, and led Tania and Jill out towards the car, a silver Buick waitingin the airport car park with the sun glinting off its windows. Tim, always the gentleman, held the back door of the car open for Tanya and James. They slid into the backseat and Jill and Tim got into the front. As Tim drove the car away from the airport, Tanya glanced out of the window at the palm trees and white and cream houses with red tile roofs and lush front gardens and smiled. She felt so happy to be somewhere sunny and really needed a break from the daily grind of working in New York.

Just then, Jill looked up at Tanya and met her eyes in the mirror on the back of the car’s built – in sunshield as she finidhed checking her makeup .

“LA is a great city” she said. “Tim and I love it since we moved here a couple of years ago ‘ we have a feeling you’ll love it.

I have a feeling we will” thought Tanya, as James reached across from his place on the seat next to her, took her neatly manicured hand in his and kissed it.

Hi Katherine! So glad you found us. Congratulations on your novel. If you need a good guide for editing, check out this post: http://positivewriter.com/how-to-edit-your-book-until-its-finished/

“Show don’t tell” is certainly more important for literary fiction than genre fiction like fantasy, but if you read really good writers like George RR Martin you’ll see they do very little telling. Still, I think we overuse the saying “show don’t tell.” It’s all about creating drama right? What “telling” usually does is that it removes all the drama, but if you can tell without oversharing, you should be fine. And after all, often showing ruins the story as much or more than telling!

But I thought your practice here was great. I don’t see any telling at all. Hope that helps!

Thank you! I have no previous experience of writing a novel. Would you mind proof reading for me? I sometimes get the impression that maybe the proofreaders were reading my manuscript whilst thinking of books they like to read themselves and comparing it to them.

Hi Katherine – no idea if you’ll see this, but here’s my two cents. I agree with Joe that there’s little or no telling in your piece (except the sentence about Tanya

feeling happy it was sunny and needing a break), but I think if anything there’s

too much showing and too much detail you don’t need. In particular, nothing

much happens during check-in or on the flight, so the drawn-out descriptions

feel unnecessary. I hope you don’t mind, but I’ve had a go at editing it, which

includes cutting it an awful lot (maybe too much). What do you think?

The flight to LA was due to leave JFK at 10:15, and it was now 10am.

‘Run,’ she said, her red high heels clicking on the tiled floor, and he rushed to keep up, dragging the suitcases.

Once they’d checked in at the American Airlines desk, they hurried through Security. James sat down heavily in the departure lounge and wiped his brow. Tanya flicked through People magazine until their flight was called.

***

The heat hit them as they left the plane. Tanya put on her Jackie O sunglasses as they crossed the tarmac towards arrivals.

‘Welcome to LA!’ James’s parents greeted them as they emerged from the crowd.

The Buick gleamed in the airport car park. Tim put the suitcases in the boot and held the back door open for them. As the car pulled away, Tanya glanced out of the window at the palm trees and cream houses with red tile roofs and lush front

gardens, and smiled. It beat the daily grind of New York hands down.

‘LA is a great place,’ said Jill. ‘I know you’ll love it.’

Tanya grinned at James. I’m sure we will, she thought, as he picked up her hand and kissed it.

The BEST advice I have found so far! THANK YOU!!

James and Sicily flew to L.A. to meet James’s parents.

Having caught an early flight, they arrived at the beach house a few hours before scheduled.

“Ugh. You won’t believe how tired I am.” yawned James. “Ma will just have to wait if she wants to talk.” he continues.

“James look!” says Sicily, “The lights are on this early in the morning?”

Seeing silhouettes of two people through the windows, both James and Sicily stared at each other realizing it appeared to be James’s parents, hugging, kissing or actually having sex.

As James uses his key to walk in, he realizes that his dad was merely helping his mother reach a set of keys hidden above the chandelier. They wanted to be sure James and Sicily could get into the mini house where they would be staying.

It was a comical sigh of relief!

well hi Joe! umm i had some difficulties in writing shortshow not tells. Think you can help me?

I mean I have some difficulites in writing it 😛

Tanya and James flew to New York city in a 747. They got their suite cases, took a taxi to their apartment, and checked into their rooms. “I can’t wait to see the theater,” Tanya said. “You’re going to love it very mucc.” James shook his head. “I don’t get it. It’s about dogs and lizards who sing and dance? Sounds sorta awesome.” Tanya smiled, “Just trust me.”

Their hotel was just a few blocks from the lines Theater so they drove. He had always seen buildings so tall or so many people walking on the road. When they got to the show, Tanya noticed his eyes were a little biger, his mouth a little slacker. The foyer was covered in black and white marble, with trillions of people milling around in gowns and beautiful clothes. He didn’t talk much. Finally, they took their seats, and the lights went dark. He took her hand.

Joe and Sammy went to los santo and checked in to the hotel after Joe said Are you ready to go see the incredible hulk Sammy said i dont want to see the incredible hulk sing and dance Joe said where seeing it because i bought a hulk tee shirt they went to the theater a saw hulk dance Sammy said hulk stinks but then hulk took their Suv right next to the hotel and chucked it right in to los santos customs car shop.

Tanya and James flew to New York city in a Boeing 747. They got their bags, and took a taxi to their hotel, and checked into their rooms. “I can’t wait to see the show,” Tanya said. “You’re going to love it.” James shook his head. “I don’t get it. It’s about Cats who sing and dance? Sounds sorta dumb.” Tanya smiled, “Just trust me.”

Their hotel was just a few blocks from the Foxwoods Theater so they walked. He had never seen buildings so tall or so many people walking on the street. When they got to the theater, Tanya noticed his eyes were a little wider, his mouth a little slacker. The foyer was covered in gold and white marble, with hundreds of people milling around in gowns and beautiful suits. He didn’t talk much. Finally, they took their seats, and the lights went down. He took her hand.

They went to the bright loud city of Los Angeles where there were thousands of people.

Then they went to the most expensive hotel there with a blue green underground swimming pool and long chairs all over. They found a restaurant because they were starving since they haven’t eaten in 7 hours. After a long day of walking and eating they went home to go to sleep in there yellow cotton beds. In the morning they went swimming in the blue green underground pool, after they went to see a play and the play was Peter Pan. They had lots of fun and went home watched T.V. for a few hours. The next day they went swimming for five hours than went to there cousins house. They found out that there house was haunted by a spirit and ran out of the house. “Were never going back there again!” “definitely not going back there”. They went back to there hotel and went to bed because in the morning they had to leave “well this vacation was fun” “yeah lets come back somtime” in the morning they went home to there blue house. Hope you enjoyed!

The stories on this blog are not at all to my taste – but the writing advice in this post is spot on.

http://lewdandfunnystories.blogspot.it/2014/11/show-dont-tell.html?view=magazine

Show not tell advice on this blog site is quite good. The stories though, are crap. The author’s name is Dong Grapper, and he gives great writing advice (I attended one of his workshops in Dungshire, Maine) but then you read his prose and think, this guy is an idiot!

http://lewdandfunnystories.blogspot.it/2014/11/show-dont-tell.html

took her out to the athletic department parking lot right up the street and as soon as we were in my car, she was all over my cock. I had been hard since I’d seen her in front of the bookstore and had been waiting for this blowjob all day long. When we came to a stop light, and I looked down to see my dickhead bulging out of her check like a stash of nuts in a chipmunk’s mouth, I thought I was gonna blow my wad right then and there.

“Jesus! You sure can suck dick!” I told her as my free hand ran across her tits.

We were approaching a fraternity house that was nice enough to invite me to all their parties and once even gave me free access to their “E-Z Fucks” list. I thought I would make a show of camaraderie, so I pressed the button that opened the sunroof.

“Okay now honey, I know you’re already doing me a big favor, but would you mind reaching down with your right hand and pressing on the gas pedal for just a few minutes?”

She gurgled her assent.

I grabbed on to the edges of the sunroof and pulled myself up so my torso was sticking up out of the sunroof. She was still blowing me, and that could be seen clearly through the windshield and the driver’s side window.

The sound of Led Zeppelin got louder and louder as my car buzzed towards my favorite frat house. I saw all the guys out on the lawn, playing catch with a football and posing for all the chicks.

Just as we passed the frat house, I raised my arms like I always do when I cross the line in the 100 yard dash and let out a big yell.

“Yeah!!!” I yelled as we zoomed by the frat house.

When I heard all the guys yell “ALL RIGHT JOHNSON!!!” simultaneously, I shot my wad deep into her throat. Apparently this shocked her greatly because she suddenly pressed hard on the accelerator, and we drove right into the Education building, plowing through a women’s studies class that was watching a docudrama about a high school gym teacher who idolized Ted Bundy.

Three lesbians were killed instantly when my car crushed them at high speed. The babe’s head went through the windshield and my dick went with it. She survived and so did my dong.

We were charged with reckless behavior, endangering the safety of a university official and negligent disruption of the learning environment under the student conduct code. We were found guilty by a tribunal of pre-law students and assorted professors picking up extra cash and fined over $100.

My track coach paid my fine. She had to pay her own, so she sucked off some Physics teacher who gave her a B minus in his class and used his position on the conduct tribunal to get the charges against her dropped. I saw her at the disco bar a few times after the trial, and each time I ignored her on purpose.

The dirt of the barren scrublands flailed wildly into the air, as a thousand horsemen thundered towards the Human capital of Helipa, a mighty sandstone fortress with foreboding ramparts aged with crumbling walls from battles long forgotten. The Eastern campaign had been raging well into its fifteenth year by now, helmed by Magnus VII, Eminance of the Third Wotonian Empire, an ageing Wotonian of around 400, tall in stature with distinctive features and a crooked nose, and a neatly flowing silver beard, though he still retained much youth in his face. Ever since King Sargus the Mighty perished after a fever leaving the Western Human Empire to his twin sons, Destar and Malastar, a brutal civil war between the twins had fractured the Empire in twain. This had allowed Magnus to conquer swaths of land in the name of Wotonia with relative ease, picking at the carcass of the dying nation. He had reached the capital by the end of Quintae, pitting his Second Legion along a huge trench network built around the capital, surrounding Destar, the boy king of the Empire. Magnus was standing, shaded by the tents around him from the relentless sun, discussing tactics with his key generals when the order came to attack the fortress. The gates had been opened by guards to throw the starving out to die as food had become scarce. The roar of the horns flared through the sky as the charge began, men on horseback and foot soldiers in phalanx alike bolted directly on the capital gates to dispose of the limited resistance sent in a futile attempt to hold the city. City guards were cut down in their stride, jets of sanguine splayed in all directions, gargled bloody breaths frothing from the mouths of those mortally wounded and being lapped up by the parched mud. The gates had been breached and a torrent of warriors flooded into the streets and alleyways. One of the legions generals, Wotillus Sextus, a close personal friend of the Eminance and decorated war hero, turned to Magnus “your orders, Magnus?. The city will soon be ours but something interests you more, what is it?” he exclaimed, voicing himself over the ruckus. “Find the boy” he sharply declared. The general summoned a contingent of the legion to follow, as he rode down the central plaza to the palace courtyard. The majority of the city was captured within hours, most of the misfit garrison were low born peasants who had never handled blade in their lives, so lowered them at the sight of an armour clad sea flowing down the streets. A huge wooden door climbed to the sky, the only obstacle standing between the Eminance and the success of fifteen years of gruesome conquest. In place of siege weapons, columns from besieged buildings were carried as rams by soldier. Thrust bluntly at the doors a few well done attempts had snapped the rusted locks and the doors flew open with tremendous force, splintering and cracking to the floor. Magnus approached the waterfall in the palatial gardens, closely followed by a well formatted line of legionnaires, Destar, the boy ‘king’ appeared to have given up, his personal guard laying down arms at their foes feet. He approached the Eminance and paused. Magnus stared him intensely, with a gaze that could cut steel. Magnus calmly, sternly spoke “Have you any last free words?” to his surprise, Destar remarked aggressively “I am no slave, nor will i ever be” before lunging for the Eminances broadsword, affixed to the left of his belt. Two praetorians of Magnus’ honour bound Sixth Legion restrained him, breaking both arms in the process and forcing him to his knees. An attempt on the life of an Eminance was paramount to treason. Unsheathing a long sharpened spatha for the scabbard of one of the Praetorians, coldly uttering “By the mercy of Wotus, i take your life” Magnus swung the sword horizontally, decapitating the king, his body slumped to the ground gushing blood into crevices on the plaza cobbles. The city stood silent, the Legion stood silent, even the air ceased to move. Magnus was not a cruel man, infact regarded by most as the greatest leader of recent history, a natural conqueror, scholar and diplomat. A relief to the Wotonian populous considering his ancestors marred past. A raucous cheer darted across the plaza, followed swiftly by others in a stirringly harmonious chorus, the Eminance’s name chanted from every available space. Legionnaires took the kings body and several others from the ruins of the town to the ramparts, pinning them to rot as a warning to others who sought to prosper from the spoils of war. Others such as the likes of the newly founded ‘Righteous Human Empire’ just east of the capital. Their presence had been well noted by the Imperial army, and many a skirmish in the past has caused chasmic animosity between the two factions.

any thoughts on my first page? does it flow well?

The dirt of the barren scrublands flailed wildly into the air, as a thousand horsemen thundered towards the Human capital of Helipa, a mighty sandstone fortress with foreboding ramparts aged with crumbling walls from battles long forgotten. The Eastern campaign had been raging well into its fifteenth year by now, helmed by Magnus VII, Eminance of the Third Wotonian Empire, an ageing Wotonian of around 400, tall in stature with distinctive features and a crooked nose, and a neatly flowing silver beard, though he still retained much youth in his face. Ever since King Sargus the Mighty perished after a fever leaving the Western Human Empire to his twin sons, Destar and Malastar, a brutal civil war between the twins had fractured the Empire in twain. This had allowed Magnus to conquer swaths of land in the name of Wotonia with relative ease, picking at the carcass of the dying nation. He had reached the capital by the end of Quintae, pitting his Second Legion along a huge trench network built around the capital, surrounding Destar, the boy king of the Empire. Magnus was standing, shaded by the tents around him from the relentless sun, discussing tactics with his key generals when the order came to attack the fortress. The gates had been opened by guards to throw the starving out to die as food had become scarce. The roar of the horns flared through the sky as the charge began, men on horseback and foot soldiers in phalanx alike bolted directly on the capital gates to dispose of the limited resistance sent in a futile attempt to hold the city. City guards were cut down in their stride, jets of sanguine splayed in all directions, gargled bloody breaths frothing from the mouths of those mortally wounded and being lapped up by the parched mud. The gates had been breached and a torrent of warriors flooded into the streets and alleyways. One of the legions generals, Wotillus Sextus, a close personal friend of the Eminance and decorated war hero, turned to Magnus “your orders, Magnus?. The city will soon be ours but something interests you more, what is it?” he exclaimed, voicing himself over the ruckus. “Find the boy” he sharply declared. The general summoned a contingent of the legion to follow, as he rode down the central plaza to the palace courtyard. The majority of the city was captured within hours, most of the misfit garrison were low born peasants who had never handled blade in their lives, so lowered them at the sight of an armour clad sea flowing down the streets. A huge wooden door climbed to the sky, the only obstacle standing between the Eminance and the success of fifteen years of gruesome conquest. In place of siege weapons, columns from besieged buildings were carried as rams by soldier. Thrust bluntly at the doors a few well done attempts had snapped the rusted locks and the doors flew open with tremendous force, splintering and cracking to the floor. Magnus approached the waterfall in the palatial gardens, closely followed by a well formatted line of legionnaires, Destar, the boy ‘king’ appeared to have given up, his personal guard laying down arms at their foes feet. He approached the Eminance and paused. Magnus stared him intensely, with a gaze that could cut steel. Magnus calmly, sternly spoke “Have you any last free words?” to his surprise, Destar remarked aggressively “I am no slave, nor will i ever be” before lunging for the Eminances broadsword, affixed to the left of his belt. Two praetorians of Magnus’ honour bound Sixth Legion restrained him, breaking both arms in the process and forcing him to his knees. An attempt on the life of an Eminance was paramount to treason. Unsheathing a long sharpened spatha for the scabbard of one of the Praetorians, coldly uttering “By the mercy of Wotus, i take your life” Magnus swung the sword horizontally, decapitating the king, his body slumped to the ground gushing blood into crevices on the plaza cobbles. The city stood silent, the Legion stood silent, even the air ceased to move. Magnus was not a cruel man, infact regarded by most as the greatest leader of recent history, a natural conqueror, scholar and diplomat. A relief to the Wotonian populous considering his ancestors marred past. A raucous cheer darted across the plaza, followed swiftly by others in a stirringly harmonious chorus, the Eminance’s name chanted from every available space. Legionnaires took the kings body and several others from the ruins of the town to the ramparts, pinning them to rot as a warning to others who sought to prosper from the spoils of war. Others such as the likes of the newly founded ‘Righteous Human Empire’ just east of the capital. Their presence had been well noted by the Imperial army, and many a skirmish in the past has caused chasmic animosity between the two factions.

any thoughts on my first page?

Great story. Funny thing though: my browser showed me just a portion of Becky’s and Carl’s discussion. It ended with the paragraph that concludes “..you were trying to get enough money to finish school. Just go with that for now”.

I thought this subtle hint was a perfect way to end the story. Could have been written by Raymond Carver. Then I realized there was more. And, having been attracted to that Carveresque room-for-your-own-imagination, that real ending was just baggage. The wonderful mystery diluted.

Here is the draft essay what I recently wrote for my English class. Let’s hope I did a good job. I’ll be much appreciated to hear your feedback here. Thank you!

I woke up in the day where I heard my mom cried with the

joyfulness. I wondered what she was crying about. I looked at another side

where I’m lying on the bed, I realized I was at the hospital. I had hard time

to breathe, my mom got scared and looking at me with the hopeful looking like