Most great stories, whether they are a Pixar film or a novel by your favorite author, follow a certain dramatic structure. When you’re getting started with writing, understanding how the structure works is difficult. Even if you go back and analyze your favorite books and films, it can still be hard to structure your own stories. That's where Freytag's Pyramid structure can help.

Freytag's Pyramid is one of the oldest dramatic structures. Developed by Gustav Freytag in the mid 19th century, this structure has become so ubiquitous, many of the best writers have used it to write their own stories, even if they didn’t know it was called Freytag’s Pyramid.

In this article, we’re going to look at Freytag’s Pyramid. I'll share what it is, give examples of how to use it, and share whether it would be helpful to use as you structure the plot of your own stories. We'll also look at how to use Scapple, a great piece of book writing software, to structure your stories based on Freytag's Pyramid.

First, though, if you want to learn more about plot and how to structure your story, check out my new book, The Write Structure, on sale for $5.99 (for a limited time!). It helps writers like you make their plot better and write books readers love. Click to get the book.

Contents

What is Dramatic Structure?

What is Freytag’s Pyramid?

Freytag’s Pyramid Plot Diagram

How to Understand Freytag’s Pyramid

Freytag’s Pyramid vs. Modern Dramatic Structure

What are the 5 Stages of Freytag’s Pyramid?

Introduction

Rising Movement

Climax

Falling Action

Catastrophe

Example of Freytag’s Pyramid: Romeo and Juliet

Should You Use Freytag’s Pyramid?

Bonus: Writing Quotes from Freytag’s Technique

Freytag’s Pyramid Creative Writing Exercise

What is Dramatic Structure?

Dramatic structure is an idea, originating in Aristotle’s Poetics, that effective stories can be broken down into elements, usually including exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution, and that when writers are constructing a story they should include these five elements.

What is Freytag’s Pyramid?

Freytag’s Pyramid is a dramatic structural framework developed by Gustav Freytag, a German playwright and novelist of the mid-nineteenth century. He theorized that effective stories could be broken into two halves, the play and counterplay, with the climax in the middle.

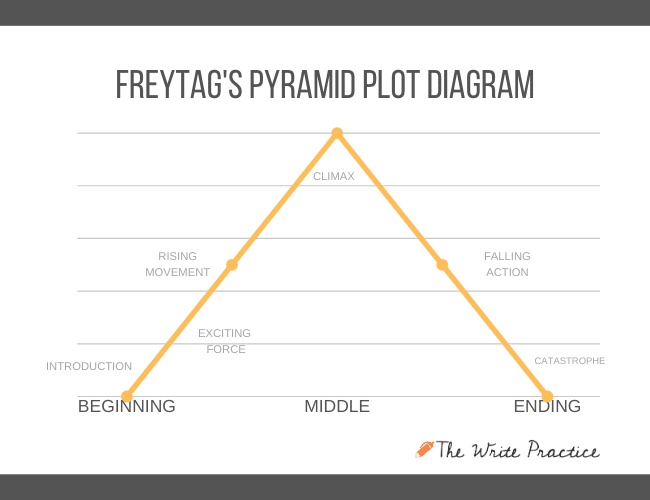

These two halves create a pyramid or triangle shape containing five dramatic elements: introduction, rising movement, climax, falling movement, and denouement or catastrophe.

<h2id=”diagram”>Freytag’s Pyramid Plot Diagram

The pyramid, sometimes called Freytag’s Triangle, is best visualized in the following diagram:

How to Understand Freytag’s Pyramid

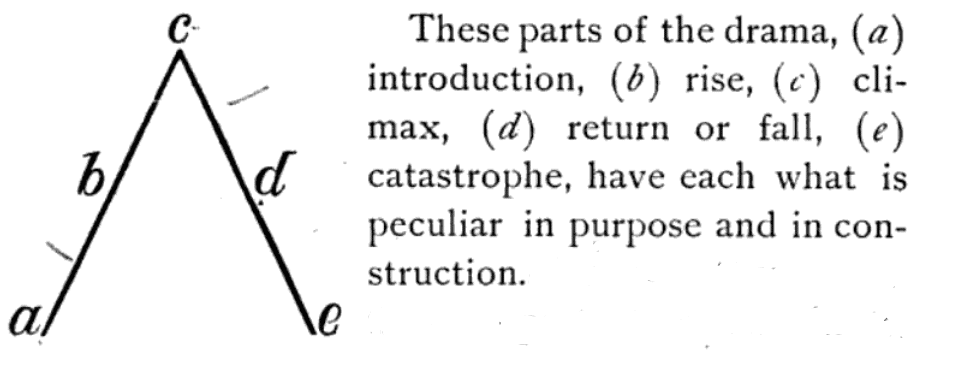

Gustav Freytag originally formulated Freytag’s Pyramid in his 1863 book Freytag’s Technique of the Drama, and over the last more than 150 years, it has become one of the most commonly taught dramatic structures in the world, finding its way into thousands of classrooms and writing workshops.

Here’s the original plot diagram (found on page 115 of Freytag’s Technique):

The plot diagram from the original translation of Freytag's Pyramid of the 1863 version of Freytag's Technique of the Drama.

The plot diagram from the original translation of Freytag's Pyramid of the 1863 version of Freytag's Technique of the Drama.

I think many of us have a kind of vague sense of this narrative structure, even if we were never formally taught it.

However, one thing I realized after actually reading Freytag’s Technique is that the structure that I learned doesn’t actually conform to how the German novelist thought of it. It surprised me that many of the terms Freytag used are different than the way it has been subsequently taught.

For example, many articles on Freytag’s Pyramid use the term “denouement” to describe part of the story structure. The word denouement, however, never appears in Freytag’s work (not even in the original German).

On top of that, I found that many of the concepts differ radically from how we generally understand them today.

Below, I’ve tried to summarize Freytag’s Pyramid based on how I understood it in Freytag’s Technique, while also including modern interpretations. But if you’re interested in this subject, it would be worth reading his book on your own.

What are the 5 Stages of Freytag’s Pyramid?

Here are definitions for the five elements or stages of Freytag’s Pyramid:

1. Introduction

The introduction contains both the exposition and “exciting force”:

Exposition. This is a scene in which no major changes occur and the point is to introduce the main characters, time period, and tone, and set up the “exciting force.”

Exciting Force. Freytag also calls this the “complication,” and other frameworks call it the “inciting incident,” when some force of will on the part of the protagonist or an outside complication forces the protagonist into motion.

2. Rising Movement

Now that the chief action has been started, the story builds in action toward the climax. Any characters who have not as of yet been introduced should be introduced here.

(Note that many people call this the “rising action,” but Freytag calls it rising movement.)

3. Climax

In Freytag’s framework, the climax occurs in the middle of the story.

In this framework, the climax can be thought of as a reflection point. If things have gone well for the protagonist, at the climax they start to fall apart tragically.

Or in a comedy, if things have been going poorly for the protagonist, things start improving.

The author should, according to Freytag, put his or her best effort into the writing of this scene, as it is the moment that carries the story as a whole.

The way that Freytag himself talks about this in Freytag’s Technique of the Drama is much less simplistic. The climax is still the point at which the story reflects and afterward becomes the mirror story, the counter-play.

But rather than just focus on the fate of the protagonist, Freytag thinks about the climax as the scene or group of scenes in which the fullest energy of the protagonist is portrayed, whether for good or ill, pathos or pride. After the climax, whatever ambition the protagonist showed is reversed against himself, and whatever suffering she endured is redeemed. In other words, the energy, values, and themes shown in the first half are reversed and undone in the second half.

As Freytag puts it, “This middle, the climax of the play, is the most important place of the structure; the action rises to this; the action falls away from this.”

4. Falling Action

In the falling action, things continue to either devolve for the protagonist or, in the case of a comedy, improve, leading up to the “force of the final suspense,” a moment before the catastrophe, when the author projects the final catastrophe and prepares the audience for it.

As Freytag says, “It is well understood that the catastrophe must not come entirely as a surprise to the audience.”

But just after this foreshadowing, there must be a moment of suspense where the slim possibility of reversal is hinted at.

“Although rational consideration make the inherent necessity of his destruction very evident . . . it is an old, unpretentious poetic device, to give the audience for a few moments a prospect of relief. This is done by means of a new slight, suspense.”

5. Catastrophe or Denouement

Freytag was chiefly focused on tragedy, not comedy, and he saw the ending phase of a story as the moment of catastrophe, in which the main character is finally undone by their own choices, actions, and energy.

After the catastrophe is a moment of catharsis, where the action of the story is resolved and the tension releases as the audience takes in the story's final outcome.

While Freytag never uses the word “denouement” in his own framework, people interpreting him have used the term to describe endings with a happy result for the protagonist.

Freytag’s Pyramid vs. Modern Dramatic Structures

Freytag's pyramid was invented nearly two hundred years ago, before the invention of the radio, film, and television transformed storytelling. So it's not surprising that plot structure theory has advanced since then. Some key elements remain the same, but some have shifted.

There are four main differences between Freytag and modern story structure theory:

1. Freytag's pyramid is great for tragedy. Modern theories are more universal.

Freytag was chiefly interested in one type of story: the tragedy. He thought it was premier form of storytelling. All the novels and plays he wrote were tragedies, and nearly all of the stories he studies in Freytag’s Technique are tragedies.

This caused him to create a story structure framework particularly suited to a specific dramatic arc, a tragedy (specifically an Icarus Story arc, which you can learn about here), but one that isn't very helpful for anyone writing a story with a happy ending.

So while Freytag’s Pyramid certainly can be helpful for writers, especially those writing tragedy, his framework is much less universal than The Write Structure, Story Grid, or even Save the Cat, all of which better describe a wider variety of stories.

2. Modern theories place the climax later in the story.

One of the core differences is the term “climax.” Freytag’s framework puts the climax in the middle of the story, where it works as the stories major turning point.

For a traditional understanding of three-act story structure—as found in Story Grid or Save the Cat—what Freytag calls the climax is instead called the “midpoint.”

See the diagram below for an example:

The climax in these frameworks occurs at the end of either the second or third acts, and often is one of the last scenes of the story, taking the location of Freytag’s catastrophe.

3. Plot Elements

Freytag wrote the first major breakdown of story structure in modern history, an amazing accomplishment.

But since he was so influential, he also gets credit for a lot of plot elements he didn't invent and never even used in the first place, like denouement (he used the term catastrophe), resolution (same), rising action (he used the term rising movement), and more.

Since then, the common story structure terms have slowly morphed into something Freytag would find unrecognizable. Worse, the new terms are still taught as “Freytag's pyramid,” even though they don't resemble his original theories.

Take a look at the differences below:

| Freytag’s Pyramid (circa 1863) | 6 Modern Plot Points* | The Write Structure |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

*While there are many variations of this, these are the plot points most often taught.

Note too that we don't include the falling action in The Write Structure framework. Here's why.

While many of these differences are minor, some of them have major implications (like the difference between Freytag's version of “climax” and the modern version of climax).

For now, just notice how these terms have morphed since Freytag.

4. Freytag used a five-act structure, while modern writers use three-act structure.

“Let a play which would be inquired after, and though seen, represented anew, be neither shorter nor longer than the fifth act,” said the Roman playwright Horace in the first century B.C.

During the enlightenment, as writers and philosophers like Freytag were dredging up these old Roman texts, five acts became the standard

The problem is five-act structure really doesn't make much sense, at least in the way that Freytag advocates (with essentially three tiny acts and two giant acts).

You can learn more about Freytag's five-act structure and why you shouldn't use it here. For most writers, a three-act structure is a much better choice.

The greek philosopher Aristotle even seems to advocate for a three-act structure in his Poetics treatise, giving the first ever recorded story structure tip, and saying, in short, that a story should have a beginning, a middle, and an end. Not exactly a profound insight, but hey, it's better than nothing!

<h2id=”example”>Example of Freytag’s Pyramid: Romeo and Juliet

Let’s break down how Freytag’s Pyramid actually works using an example, in this case one that most people are familiar with and Freytag himself used, Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet:

To better understand how the five act structure works, I’ve also created an annotated version of Romeo and Juliet.

In this document, you’ll be able to click through the table of contents, exploring each act, and seeing where it ends and where the next act begins. You’ll also be able to spot the exciting force and the force of the final suspense.

Explore Romeo and Juliet annotated with the five act structure here »

Then, below I'll talk more about how each section of Freytag's Pyramid works in the play below.

Introduction

We start by getting a sense of the rivalry between the Montagues and the Capulets. As Freytag says, “an open street, brawls and the clatter of swords of hostile parties.”

Then meet the important characters, including Romeo who is getting over an infatuation with another girl; Mercutio, Romeo’s bestie; and Tybalt, the Capulet attack dog and cousin to Juliet.

We also meet Juliet, her parents, and her nurse.

Exciting force: Romeo and his posse decide to attend the Capulets’ ball.

A few notes about the introduction:

- The introduction is pretty short, especially compared to the rising movement.

- No major changes occur here until the exciting force.

- The exciting force should be a major change, but Freytag found it to not be strong enough in Romeo and Juliet. He says, “If the exciting force is ever too small and weak for him, as in Romeo and Juliet, he understands how to strengthen it. Therefore, Romeo, after his conclusion to intrude upon the Capulets, must pronounce his gloomy forebodings before the house.”

Rising Movement: The Couples Meet, Get Married, Then Get Into Trouble

Freytag identifies four stages in the rising action:

Stage One: The masked ball. Includes Juliet preparing for the ball, Romeo with his posse before sneaking into the ball, Tybalt’s anger at the Montagues being present at the ball, Romeo first seeing Juliet, Romeo and Juliet’s first conversation, and finally Juliet’s debrief with her nurse.

Stage Two: The garden scene. Includes Romeo’s friends looking for him and Romeo and Juliet’s conversation and decision to get married.

Stage Three: The marriage. Includes four scenes leading up to Friar Laurence marrying the couple and their post-.

Stage Four: Tybalt’s death. Romeo runs into Tybalt. They fight and Tybalt is killed.

A few notes about the rising action:

- The rising action covers a lot of ground, from the meet cute to the marriage to the major complication in Tybalt’s death.

- For some reason, Freytag totally skips over Mercutio’s death, which I found surprising. Mercutio is the man!

- Personally, if I were putting this play into a three-act structure, I would end act one with the garden scene and begin act two with their preparations for marriage. But that’s me. The point, though, is that this approach differs from the way most people look at a three-act story structure today. In fact, Freytag was more interested in a five-act structure.

Climax

Juliet urges Rome to flee and Romeo says goodbye to Juliet.

A few notes about the climax:

- The climax is relatively short, with just one major scene.

- The climax occurs toward the middle of the play (slightly right, maybe ⅗ of the way through the story).

- Honestly, it’s not that climactic. Today, most writers would probably call the final death scene the climax, not this scene. Instead, we would call this the midpoint, a turning point leading up to “the dark night of the soul.”

- This is when the counter-play begins. In the first half, the play, the lovers unite. In the counter-play, the lovers separate, until ultimately, they are separated by death.

Falling Action

Romeo is in exile. Juliet’s parents force her into an engagement with Paris, and to avoid it, Friar Laurence helps her fake her own death. Believing his wife is dead, Romeo leaves exile after purchasing poison to end his life from an apothecary.

Force of the final suspense: Romeo faces Paris in the graveyard and kills him, and enters Juliet’s tomb. Friar Laurence enters the graveyard behind him.

A few notes about the falling action:

- Even though this section makes up a large amount of the story, Freytag doesn’t concern himself very much with it. In fact, while every other step in the pyramid has its own section, Freytag doesn’t even bother creating a section for this, as if he assumes that the scenes in the Falling Action will write themselves.

- Freytag does focus on the force of the final suspense, though, and sees it first as a foreshadowing of the final catastrophe and then a momentary possibility of reversal.

Catastrophe

Rome discovers Juliet, apparently dead, and gives a final speech before he kills himself with poison. As he is dying Juliet wakes up from her pretend death to discover Romeo dying. They share a final kiss. Juliet ends her life with Romeo’s dagger.

Friar Laurence arrives too late to save them. Then the Prince, the Montagues, and the Capulets join them and the Prince condemns their rivalry and calls for a final peace.

Some notes about the catastrophe:

- The catastrophe section, like the climax, is quite short, with just the actual catastrophic scene and one scene of fallout from the event.

- Today, most writers would call this scene the climax of the story.

How to Use Scapple to Plot and Structure Your Story with Freytag’s Pyramid

One of my favorite ways to plot and structure my stories is through Scapple, a piece of book writing software made by the creators of Scrivener.

To give you a sense of how to use Scapple to structure the plot of your story, here's a video demoing Scapple by plotting Romeo and Juliet using Freytag’s Pyramid:

Interested in checking out Scapple? You can learn more about it here.

So that's it. Romeo and Juliet in Freytag's Pyramid plot diagram created on Scapple.

If this is something that you would like access to, we have a link to Scapple in the description.

This is a tool I personally use when I'm structuring my stories, and I think it could definitely help you with your own writing.

There's a free trial as well, and I think it's only like $18, so it's a pretty good deal. I would definitely recommend it for your creative writing.

Should You Use Freytag’s Pyramid?

Maybe.

I think Freytag’s Pyramid is most helpful if you’re writing tragedy and if you want a framework to help you think through your story from the perspective of two separate halves with a central scene in the middle that acts as a reflection point.

However, for most stories, you'll want to use a more flexible, universal framework like Story Grid or The Write Structure.

You can learn more about Story Grid and its five commandment in our Crisis guide or from the Story Grid book.

Beyond just the pyramid, though, I found much of Freytag’s Technique of the Drama to be a fascinating methodology and study of storytelling. The way he understood plot and story structure was unique and challenging, and once I got over some of his major cultural pitfalls, I got a lot out of reading it.

All that’s to say, if you can handle reading a text that was written in the mid 1800s, check it out. You can read Freytag’s Technique of the Drama for free here.

Bonus: Writing Quotes from Freytag’s Technique

Here are some of my favorite writing quotes from Freytag’s Technique of the Drama:

“The poet of the present is inclined to look with amazement upon a method of work in which the structure of scenes, the treatment of characters, and the sequence of effects were governed by a transmitted code of fixed technical rules.”

“When the poet has once thus infused his own soul into the material, then he adopts from the real account some things which suit his purpose.”

“For thousands of years the human race has thus transposed for itself life in heaven and on earth; it has abundantly endowed its representations of the divine with human attributes. All heroic tradition has sprung from such a transformation of impressions from religious life, history, or natural objects, into poetic ideas.”

“The dramatic includes those emotions of the soul which steel themselves to will…, also the inner processes which man experiences from the first glow of perception to passionate desire and action, as well as the influences which one’s own and other’s deeds exert upon the soul; also the rushing forth of will power from the depths of man’s soul toward the external world, and the influx of fashioning influences from the outer world into man’s inmost being; also the coming into being of a deed, and its consequences on the human soul.”

“An action, in itself, is not dramatic. Passionate feeling, in itself, is not dramatic. Not the presentation of a passion for itself, but of a passion which leads to action is the business of dramatic art; not the presentation of an event for itself, but for its effect on a human soul is the dramatist’s mission. The exposition of passionate emotions as such, is in the province of the lyric poet; the depicting of thrilling events is the task of the epic poet.”

“Through this linking together of incidents, dramatic idealization is effected.”

“What history is able to declare can be to the poet only the frame within which he paints his most brilliant colors, the most secret revelations of human nature.”

“The structure of the drama must show these two contrasted elements of the dramatic joined in a unity, efflux and influx of will-power, the accomplishment of a deed and its reaction on the soul, movement and counter-movement, strife and counter-strife, rising and sinking, binding and loosing.”

Need more plot help? After you work on practicing this structure in the exercise section below, check out my new book The Write Structure which helps writers make their plot better and write books readers love. Low price for a limited time!

Need more plot help? After you work on practicing this structure in the exercise section below, check out my new book The Write Structure which helps writers make their plot better and write books readers love. Low price for a limited time!

How about you? What questions do you have about Freytag's pyramid? What dramatic structure framework do you follow in your writing? Let me know in the comments.

PRACTICE

Let’s practice using Freytag’s Pyramid with this creative writing exercise:

Outline a tragedy using Freytag’s five elements:

- Introduction (including the Exposition and Exciting Force)

- Rising Movement

- Climax

- Falling Force

- Catastrophe

Write one or two sentences for each event.

Take fifteen minutes to write. When you’re finished, post your outline in the Pro Practice Workshop for feedback. And if you post, be sure to give feedback on at least three other writers’ outlines.

Happy writing!

0 Comments